![]()

Chapter 1

Natural Products in Drug Discovery: Recent Advances

Gordon M. Cragg, Paul G. Grothaus, and David J. Newman

1.1 Introduction

Throughout the ages, Nature has provided humans with the means to cater for their basic needs, not the least of which are medicines for the treatment of a wide spectrum of diseases. Plants, in particular, played a significant role forming the basis of sophisticated traditional medicine systems. Records dating from around 2600 BCE document the uses of approximately 1000 plant-derived substances in Mesopotamia. These included oils of

Cedrus species (cedar) and

Cupressus sempervirens (cypress),

Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice),

Commiphora species (myrrh), and

Papaver somniferum (poppy juice), all of which continue to be used today for the treatment of ailments ranging from coughs and colds to parasitic infections and inflammation [1]. Although Egyptian medicine dates from about 2900 BCE, the best-known record is the “Ebers Papyrus,” which dates from 1500 BCE and documents over 700 drugs, mostly of plant origin [1]. The Chinese

Materia Medica has been extensively documented over the centuries [2]; the first record dates from about 1100 BCE (Wu Shi Er Bing Fang, containing 52 prescriptions), and is followed by works such as the Shennong Herbal (

100 BCE; 365 drugs) and the Tang Herbal (659 CE; 850 drugs). Likewise, documentation of the Indian Ayurvedic system dates from before 1000 BCE (Charaka; Sushruta and Samhitas with 341 and 516 drugs, respectively) [3, 4].

The Greeks and Romans made substantial contributions to the rational development of the use of herbal drugs in the ancient “Western” world. The Greek physician, Dioscorides (100 CE), accurately documented the collection, storage, and use of medicinal herbs while traveling with Roman armies throughout the then “known world,” while Galen (130–200 CE), a practitioner and teacher of pharmacy and medicine in Rome, is well known for his complex prescriptions and formulae used in compounding drugs. It was, however, the Arabs who preserved much of the Greco-Roman expertise during the Dark and Middle Ages (fifth–twelfth centuries), and they expanded it to include the use of their own resources, together with Chinese and Indian herbs unknown to the Greco-Roman world. A comprehensive review of the history of medicine may be found on the website of the National Library of Medicine (NLM), United States National Institutes of Health (NIH), at http://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/collections/archives/index.html.

1.2 The Role of Traditional Medicine and Plants in Drug Discovery

Plant-based systems have continued to play an essential role in health care of many cultures [5, 6], and the World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that approximately 65% of the world's population relies mainly on plant-derived traditional medicines for their primary health care [7]. Plant products also play an important role in the health care systems of the remaining population, mainly residing in “developed” countries [7]. Of 122 compounds identified in a survey of plant-derived pure compounds used as drugs in countries hosting WHO-Traditional Medicine Centers, 80% were found to be used for the same or related ethnomedical purposes, and were derived from only 94 plant species [7]. Relevant examples are given by Fabricant and Farnsworth [8].

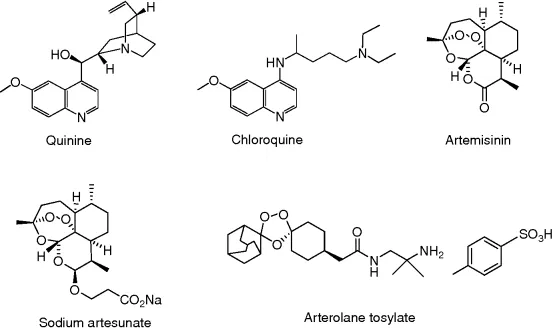

Probably the best example of ethnomedicine's role in guiding drug discovery and development is that of the antimalarial drugs, particularly, quinine and artemisinin. The isolation of quinine (Figure 1.1) was reported in 1820 by the French pharmacists, Caventou and Pelletier from the bark of Cinchona species (e.g., Cinchona officinalis) [9]. The bark, long used by indigenous groups in the Amazon region for the treatment of fevers, was introduced into Europe in the early 1600s for the treatment of malaria, and quinine formed the basis for the synthesis of the commonly used antimalarial drugs, chloroquine (Figure 1.1) and mefloquine, which largely replaced quinine in the mid-twentieth century. As resistance to both these drugs developed in many tropical regions, another plant having a long history of use in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) for the treatment of fevers, Artemisia annua (Qinghaosu), gained prominence [10], and the discovery of artemisinin (Figure 1.1) by Chinese scientists in 1971 provided an exciting new natural product lead compound [11]. Artemisinin analogs, such as artesunate (Figure 1.1), are now used for the treatment of malaria in many countries, and many other analogs of artemisinin have been prepared in attempts to improve its activity and utility [12]. These include totally synthetic molecules with the trioxane moiety included, such as arterolane tosylate (OZ277, Figure 1.1) [13], which is in Phase II trials under Ranbaxy, artemisinin dimers [14], and the amino-artemisinin, artemisone [15].

Resistance to artemisinin-based drugs is now being observed [16]. In order to counter this development, variations on the basic structure have been launched in combination with other antimalarials (usually variations on the chloroquine structure) such as dihydroartemisinin and piperaquine phosphate (Artekin®); artemether and lumefantrine (Coartem®); artesunate and mefloquine (Artequin®); and artesunate, sulfamethoxypyrazine, and pyrimethamine (Co-Arinate®). Currently there is one other fixed dose combination with an artemisinin derivative in Phase III clinical trials, pyronaridine/artesunate (Pyramax®) [17, 18].

While artemisinin and more soluble derivatives have altered the treatment of resistant malaria, the costs of collection of sufficient quantities of the source plants is high, and the overall cost of the drugs may exceed what can be afforded by the countries where the drug is required for general treatment. In an attempt to avoid dependence on wild or even cultivated plant harvesting and thereby reduce costs, the Keasling group, in conjunction with the Gates Foundation and Amyris Pharmaceuticals, has transferred the genes from the producing plant into Escherichia coli and also Saccharomyces cerevisiae. They have successfully expressed the base terpene (amorpha-4,11-diene) and followed up with modification of the base structure both chemically, and to some extent, biochemically via P450 enzymes [19]. Titers exceeding 25 g/L of amorpha-4,11-diene have been produced by fermentation and are followed by chemical conversion to artemisinin, thereby allowing for the development of a potentially viable process to provide an alternative source of artemisinin [20].

Other significant drugs developed from traditional medicinal plants include: the antihypertensive agent, reserpine, isolated from Rauwolfia serpentina used in Ayurvedic medicine for the treatment of snakebite and other ailments [3]; ephedrine, from Ephedra sinica (Ma Huang), a plant long used in traditional Chinese medicine, and the basis for the synthesis of the antiasthma agents (beta agonists), salbutamol and salmetrol; and the muscle relaxant, tubocurarine, isolated from Chondrodendron and Curarea species used by indigenous groups in the Amazon as the basis for the arrow poison, curare [9]. Although plants have a long history of use in the treatment of cancer [21], cancer, as a specific disease entity, is likely to be poorly defined in terms of folklore and traditional medicine, and consequently many of the claims for the efficacy of such treatment should be viewed with some skepticism [22]. Of the plant-derived anticancer drugs in clinical use, some of the best known are the so-called vinca alkaloids, vinblastine and vincristine, isolated from the Madagascar periwinkle, Catharanthus roseus; etoposide and teniposide which are semisynthetic derivatives of the natural product epipodophyllotoxin; paclitaxel (Taxol®), which occurs along with several key precursors (the baccatins) in the leaves of various Taxus species, and the semisynthetic analog, docetaxel (Taxotere®); and topotecan (hycamptamine), irinotecan (CPT-11), 9-amino- and 9-nitro-camptothecin, all semisynthetically derived from camptothecin, isolated from the Chinese ornamental tree, Camptotheca acuminata. These agents together with other plant-derived anticancer agents have been reviewed [23, 24].

1.3 The Role of Marine Organisms in Drug Discovery

While marine organisms do not have a significant history of use in traditional medicine, the world's oceans, covering more than 70% of the earth's surface, represent an enormous resource for the discovery of potential chemotherapeutic agents. Of the 33 animal phyla listed by Margulis and Schwartz [25], 32 are represented in aquatic environments, with 15 being exclusively marine, 17 marine and nonmarine (with 5 of these having more than 95% of their species only in marine environments), and only 1, Onychophora, being exclusively nonmarine. With the development of reliable scuba diving techniques enabling the routine accessibility of depths close to 40 m, the marine environment has been increasingly explored as a source of novel bioactive agents. The use of remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) permits the performance of selective deepwater collections with minimal environmental damage, but the high cost of ROV operations precludes their extensive use in routine collection operations. The systematic investigation of marine environments as sources of novel biologically active agents only began in earnest in the mid-1970s, and the rapidly increasing pace of these investigations over the recent decades has clearly demonstrated that the marine environment is a rich source of bioactive compounds, many of which belong to totally novel chemical classes not found in terrestrial sources [26].

While the focus of research has been on the discovery of potential new anticancer agents [23], the first marine-derived product to gain approval as a drug was Ziconotide, a non-narcotic analgesic that is currently marketed as Prialt® [27]. This compound is a const...