- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Stillbirth remains a major and tragic obstetric complication

The number of deaths due to stillbirth are greater than those due to preterm birth and sudden infant death syndrome combined.

Stillbirth: Prediction, Prevention and Management provides a comprehensive guide to the topic of stillbirth. Distilling recent groundbreaking research, expert authors consider:

- The epidemiology of stillbirth throughout the world

- The various possible causes of stillbirth

- The psychological effects on mothers and families who suffer a stillbirth

- Management of stillbirth

- Managing pregnancies following stillbirth

Stillbirth: Prediction, Prevention and Management is packed with crucial evidence-based information and practical insights. It enables all obstetric healthcare providers to manage one of the most traumatic yet all too common situations they will encounter.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Stillbirth by Catherine Y. Spong in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicina & Ginecología, obstetricia y partería. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Epidemiology and Scope of the Problem

CHAPTER 1

High Income Countries

Stillbirth and the definition “problem”

One of the difficulties in the study of stillbirth is that stillbirths are universally undercounted especially at lower ages of gestation. What constitutes a “stillbirth” varies considerably between countries, and while a universal definition has been desired, it is unlikely that a globally accepted definition will be agreed upon. The lower gestational age limit that divides a “miscarriage” from a “stillbirth” depends if a country has resources to collect information and if the intention of the data collection is to count the deaths that could possibly have “survived.” In the United Kingdom, reporting of deaths begins at 24 weeks (presumably because the mortality of those born prior to 24 is so high); in most developing countries there is very little data about losses prior to 28 weeks of gestation.

The term fetal death, fetal demise, stillbirth, and stillborn all refer to the delivery of a fetus showing no signs of life. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines stillbirth as a “fetal death late in pregnancy” and allows each country to define the gestational age at which a fetal death is considered a stillbirth for reporting purposes [1]. A moderate proportion of countries have extrapolated from the WHO’s definition of what constitutes the “perinatal period” to define stillbirth (≥500 g, or if the weight is not known, with a gestational age greater than 22 completed weeks (154 days)). But even among developed countries the gestational age at which fetal losses are reported ranges from 16 weeks (The Netherlands) to 28 weeks (Sweden) [2]. Sweden recently revised their reporting laws because of pressures from parental advocacy groups and increasing numbers of live-born infants born prior to 28 weeks, but the stillborn counterparts were not included in national statistics. Other factors that influence the reported stillbirth rate are the accuracy of gestational age dating; whether obstetric providers are accurately educated on the definition of a “liveborn” or “stillborn”; if terminations of pregnancy for lethal or sublethal anomalies are specifically excluded; and if the inevitable previable spontaneous losses that results in a stillborn had labor augmented are included.

Within the United States, terminations of pregnancy for anomalies and augmented previable losses are specifically excluded from the stillbirth statistics but misclassification of these losses is common. Duke et al. compared fetal death reports to the reports generated from the active birth defects surveillance program in the Atlanta area. They found that 13% of fetal deaths should have been excluded from the fetal death statistics because the losses involved induction or augmentation of labor [3]. It is probable that providers recognize the intention of parents (the strong desire to have had a viable healthy pregnancy) and may fill out a fetal death report rather than report the loss as a termination of pregnancy or abortion.

In the United States, because the definition of stillbirth is determined by each state, there are significant variations which can substantially change the reported stillbirth rate by as much as 50% [4]. National reporting uses 20 weeks of gestation or 350 g if the gestational age is not known. The standardized definition for fetal mortality used by the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) is similar to the WHO definition but adds that a stillbirth must have “the absence of breathing, heart beats, pulsation of the umbilical cord, or definite movements of voluntary muscles” [5]. As advances in obstetrics occur both the neonatal and stillbirth rates decrease but the stillbirths less so, leaving stillbirth the largest contributor to perinatal mortality [6].

Scope of the problem

Compared to other health outcomes and the disease burden, the scope of stillbirth has been overlooked by many, including those who have the opportunity to prioritize spending for research and ultimately to devise and implement prevention strategies. In the United States, the chances that a pregnancy will end as a stillbirth is about 1/200 for white women and 1/87 for black women [7]. Stillbirth occurs more often than deaths due to AIDS and viral hepatitis combined; stillbirth is 10 times more common than sudden infant death syndrome, nearly 5 times more common than infant deaths related to congenital anomalies, and 5 times more often than postnatal deaths due to prematurity [8].

There are many downstream consequences of stillbirth, the most significant and long lasting being experienced by mothers. Women who experience stillbirth are at an increased risk of multiple maladies including depression, anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder, somatization disorder, and family disorganization [9] (see Chapter 13).

The reason that the scope of the problem has been overlooked is multifactorial. Many people still consider stillbirths as “God’s Will” and that death before birth counts less than those after, but for many parents a stillbirth represents loss of chance and a family member. Until recently goals for the reduction of stillbirth were not included as an important health indicator, yet stillbirths are a measurable “tip of the iceberg.” Stillbirth rates reflect a woman’s preconceptual health and nutrition status, her access to good care including contraception, first-trimester care, screening for infectious diseases and congenital anomalies, disease identification and management, and adequate care during labor which includes fetal monitoring, timely access to cesarean section and IV antibiotics.

Trends in stillbirth rates

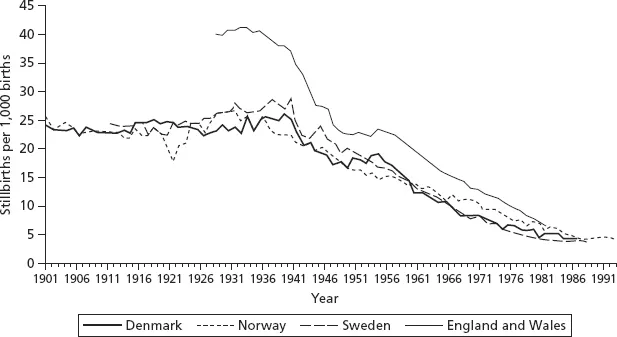

The study of stillbirth trends in historical cohorts and among developing countries identifies factors that affect stillbirth rates and are therefore most amenable to change. Countries where longitudinal data on stillbirths are kept (Denmark, Sweden, Norway, England, and Wales among others), many stillbirth rates remained relatively stable from the 1900s until the early 1940s [10]. After this time period there began a significant decline which continued but then leveled out in the mid-1980s (Figure 1.1) [10]. Interestingly, the increasing focus on the study of stillbirth in the United Kingdom was thought to be a reflection on the decline of the fertility rate; J.A. Ryle, Professor of Social Medicine at Oxford, wrote in 1949 that there was a need to reduce stillbirths as they were a “wastage of human life” and “as a matter of national accountancy we can no longer afford to lose so many potential citizens” [10].

Figure 1.1 Stillbirth rates in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and England/Wales, 1901–1990. (Data from Ref. [10].)

Vallgarda reviewed the characteristics of stillbirths that were 32 weeks of gestation or greater in Denmark from 1938 to 1947 and found that during this time period, stillbirths were reduced from 24.9 to 16.3/1,000 births (a 35% reduction). This correlated with a reduction in the numbers of women having births at home (reduced from 50% to 35% of births). In addition, in 1945, Denmark introduced a law that provided free antepartum care, which was widely used by women (70% of women initially attended prenatal care and by the 1960s this had risen to almost 100%). The types of stillbirths most noted to have decreased were those due to asphyxia in labor, malformations, bleeding, and disease of the mother [10].

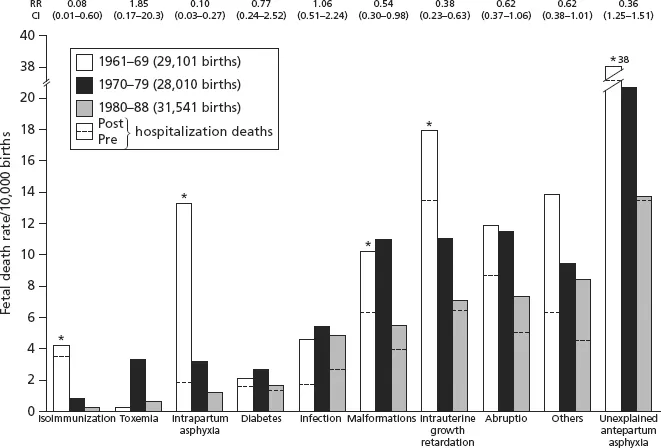

Asphyxia in labor

In a Canadian hospital based study that evaluated specific causes of death of babies 20 weeks (or 500 g) or more over more than three decades, there were two causes of fetal death that were reduced by more than 95% (Figure 1.2) [11]. During the 1960s, intrapartum stillbirth was the third most common type of stillbirth (with those that were unexplained and related to growth restriction being more common). With the introduction of intrapartum monitoring and the availability of emergency cesarean section, the proportion of stillbirths that were due to asphyxia in labor dropped from 11% to 2% of total stillbirths with a rate of 0.2/1,000 births [11]. In general, intrapartum asphyxic deaths in term or near-term babies that occur more often than 1/1,000 births suggests a significant potential for improvements in quality of care in the labor and delivery unit [12, 13].

Figure 1.2 Specific causes of stillbirth during three decades in a Canadian hospital, both prior to and after hospitalization per 10,000 births. (Data from Ref. [11].)

Rh iso-immunization

Stillbirth due to Rh iso-immunization has become a rare event in developed countries. In the same Canadian dataset that tracked changes in stillbirth over time, the authors noted a 95% reduction of these deaths during the study period of the 1960s to the early 1980s [11]. Initially Rhogam administration was given after the birth of an Rh-positive baby, and this helped reduced Rh iso-immunization considerably, but when the 28-week administration was introduced in the 1970s, the number of stillbirths were reduced even further making this now a very rare cause of stillbirth (less than 1/10,000 births) (Figure 1.2).

Congenital anomalies

The third cause of death that was notably reduced were those related to malformations. The rates of perinatal deaths due to congenital anomalies varies significantly based on maternal nutrition, environmental exposures, resources in the health systems, varied policies on screening for congenital anomalies, and the availability of terminations of pregnancy [12–15]. Within 10 European population-based cohorts for the MOSAIC study, 85% of terminations after 22 weeks of gestation were for congenital anomalies with 50% of these occurring between 22 and 23 weeks of gestation and the rest later [15]. Exclusion of terminations of pregnancy reduced the reported stillbirth rate by half. Within the 10 European countries, the percent of stillbirths related to congenital anomalies varied significantly. In Poland where the policy for termination of pregnancies is quite restrictive, the proportion of stillbirths related to congenital anomalies was 34%, in the United Kingdom where the policies for terminations of pregnancy for congenital anomalies is more liberal, these deaths account for only 3.8% of stillbirths [14]. Obviously for parents a termination of pregnancy for congenital anomalies is a traumatic event, the pregnancy outcome however is not typically included in the stillbirth statistics [3, 14, 15].

Over the past 50 years in the United States there was an approximately 70% reduction of late losses (defined as 28 weeks or more), whereas there has been virtually no decrease in early losses (20–28 weeks), since the 1990s the decline has slowed with the number of early fetal deaths exceeding the number of late losses (Figure 1.3) [16]. Unfortunately, within the United States there has not been a large longitudinal study of the specific causes of stillbirth, but there is a large body of evidence ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title

- Copyright

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- Part I: Epidemiology and Scope of the Problem

- Part II: Etiology/Causes

- Part III: Management of the Patient with a Stillbirth

- Appendix: Multidimensional Integrative Stillbirth Systems Model

- Index