![]()

Chapter 1 Sandström’s discovery

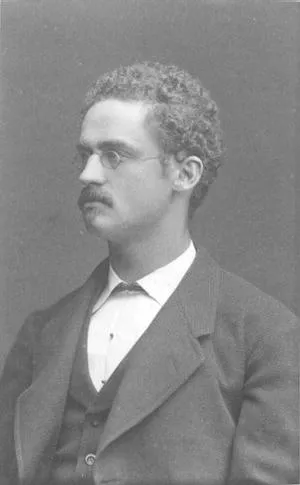

The story of the small glands that no one knew existed began in Uppsala, Sweden in the summer of 1877. Ivar Sandström was studying medicine at the university in Uppsala and was employed as a temporary research assistant to Professor Edward Clason in the Anatomy Department. Born in 1852, Ivar Sandström was the fifth child in a family of seven siblings. His father had died of cholera before the young Ivar had begun school, leaving behind substantial debts. Sandström began his medical studies in the fall of 1872 but it took a long time before he was able to finish. For economic, social and personal reasons, Sandström would not receive his medical degree until after 15 years of study. At that time, medical studies were usually completed in ten years. Sandström worked while he studied whenever he was able. He needed the summer job at the Anatomy department and although the salary was not very high, the money was useful.

August Strindberg, one of Sweden’s greatest writers, described the early summer atmosphere in Uppsala at that time in these words:

“It was spring once again and the friends had gone their separate ways, some had gone off to recruitment meetings, others to jobs in the countryside, and still others had returned to seaside resorts: he was alone in the city and envisioned a dreadful summer ahead in Uppsala where the summers could be unbearable.

One afternoon in May he had sat reading in Carolina Park, and was now walking up the Castle Hill to see a bit of the horizon. The landscape is not exactly beautiful, but it doesn’t make one long for the countryside, rather it awakens the imagination to thoughts of the sea; and he could see a steamboat push its way ahead through the dreadful fallow fields because he was born near the coast and was homesick. He envisioned all of the horrors of the coming summer and he wished it was autumn again.”

Ivar Sandström was melancholy by nature, and perhaps he felt that way.

Sandström’s introduction to medical research involved an event that must have been a shocking experience. It is a telling story about the state of the social-legal system and also perhaps about the level of medical knowledge in Sweden at the time. The scene was a place of execution in Central Sweden where professors Frithiof Holmgren, Axel Key and Edward Clason, along with Sandström and two other assistants from Uppsala had gone to make medical observations. What these medical men and over 2000 spectators were about to witness was the last act of one of the most renowned crimes in Swedish criminal history. Two relapsed criminals, Gustaf Hjert and Conrad Tektor, had been sentenced to death by beheading for a double homicide two years earlier. The executions of Hjert and Tektor were scheduled to take place simultaneously on 18th May, 1876 at 7 am at two different locations; Hjert near the murder scene and Tektor on the island of Gotland. Clason and Sandström attended Hjert’s execution with the intention to seize the opportunity to access fresh material for anatomical and histological studies. This was possible because Swedish law at the time considered the body of an individual who had been sentenced to death to be the property of the state. Professor Holmgren and his assistants were there to make observations in order to clarify “how long does a person maintain consciousness after the head has been parted from the body?”

Hjert’s execution was a disastrous event. The authorities had urged locals to attend and even school classes with children were present. Immediately after Hjert had been beheaded, Professor Holmgren rushed to the head and looked into the eyes of the executed man. Holmgren found the eyes to be wide open with the pupils strongly contracted, but after 15 seconds the eyes were one-third concealed by the eyelids and the pupils began to widen. The face was without expression during the first minute after which some rhythmic movements appeared. “He is still alive!” one of the spectators shouted. After two minutes the face was still. While Holmgren made his observations several spectators rushed toward the body and gathered blood in spoons and bowls since according to popular legend blood from a recently dead person could be used to treat “falling sickness” (epilepsy). Holmgren later stated in a report that his study showed that “a decapitated head is incapable of making any observations” and that no consciousness remains after decapitation. The execution must have given indelible memories to the 24-year-old Sandström.

Sandström’s job at the Anatomy Department was to dissect animals. It was slow and solitary work that required patience and precision. However, this did not worry him; being somewhat of a loner, he was most comfortable on his own. As in most of the anatomy departments around the world, comparative anatomy was a major subject studying the structural differences in anatomy between different animal species. It so happened that when Sandström was dissecting a dog he came across some structures that he did not recognise. In 1880 he wrote in the publication that would come to be the seminal text in the field:

“Almost three years ago I found on the thyroid of a little dog a tiny growth, barely the size of a hemp seed which lay enclosed within the same capsule of tissues as that gland, though it was dissimilar in its lighter color.”

He named the four small structures that he found in the neck glandulae parathyroidea:

“An individual name for these structures seems appropriate . . . . both due to their substantial difference in appearance . . . . as well as their consistent localization.”

The name parathyroidea was ingenious because it describes the exact location of the organ beside the thyroid (from the Greek para: ‘beside’ and thyroidea: ‘thyroid gland’).

It is understandable that this young medical student was initially skeptical as to whether he had really found an organ that had never been described before. Sandström wrote:

“The existence of a hitherto unknown gland in animals that have so often been the object of anatomical examinations prompted a thorough search in the region around the thyroid in humans as well, even though the probability of finding something that had not been observed before seemed so minute that it was only out of consideration for the thoroughness of the examination, rather than in the hope of finding something new, that I undertook a careful investigation of the tissues surrounding the thyroid.”

Obviously, neither Sandström nor his colleagues in the Anatomy Department could understand the potential significance of this discovery and further examinations were not undertaken for almost three years:

“However, time and material did not allow for the completion of the examinations, and it was only during the winter that I had the possibility of continuing them.”

After a hiatus of three years, Sandström continued with his project and carried out comparative anatomical studies on cats, oxen, horses, and rabbits, finding parathyroids in all of these animals. Naturally, the greatest challenge was to see whether parathyroids could be identified in humans. Here he was also very methodical, dissecting 50 corpses. He found that the structures were constant in 43 cases, but in five cases he found only one gland on each side, and in two cases only one gland on one side. Today we know that humans almost always have four parathyroids, and in exceptional cases one or a few more. Sandström discovered what every surgeon knows who operates on parathyroids nowadays, namely that the places where the four glands are located can vary and that it can sometimes be difficult to locate all of the glands. As an anatomist and histologist, Sandström could not go further than to describe the appearance of the organ. Naturally enough, he had no clue as to what function, if any, the parathyroids had; however he assumed that they arose from undeveloped thyroid structures and predicted that “later on pathologists would find tumors in them.”

It is probable that Sandström himself was very close to discovering a tumour in one of the glands he examined. He discovered a cyst (a clearly defined hollow space) in a gland. However, the slide material was so decomposed that he was not able to depict the microscope image in detail. The occurrence of cysts in normal parathyroids is unusual, but they appear occasionally in glands that have turned into tumours.

On reviewing the available literature, Sandström found that two researchers had observed the glands before him, although he “could not deny that there might have also been others.” Sandström noted in his report that the two German pathologists, Robert Remak and Rudolph Virchow, had observed the parathyroids earlier. Yet these prominent pathologists had not understood that these small formations actually constituted an entirely unique organ, and that they had a particular function as well. Nevertheless, for some reason, the time was right for the parathyroids to be discovered. The pathologist D. A. Welsh stated in his dissertation in 1898 that some 20 German, French, Italian, and English researchers had observed the parathyroids during the years 1876−1881, around the time of Sandström’s publication (1880), but none of these reports offered anything more than what Sandström had observed, and therefore they were largely ignored. Thus a number of anatomists had discovered the parathyroids independently around 1880 even though pathologists, and to some extent surgeons, had performed dissections in this region without having observed these minute structures.

Simultaneous (parallel) discoveries or inventions are, in fact, not that unusual. One of the more famous examples is the discovery of oxygen that was made by Carl Wilhelm Scheele in 1772 and by Joseph Priestly in 1774. That discoveries are made by several different researchers independently can often be explained by the fact that prior observations presented unexpected or conflicting results which caused people to begin questioning the existing concepts. A new discovery is in the air, so to speak, and this is usually a consequence of the intellectual climate or of new technical achievements at a specific point in time. The historian Robert Thurston describes the phenomenon of simultaneous discoveries in the following way:

“Every great discovery is usually a compilation of a number of smaller discoveries or the last step in a development. It is not a matter of creation in the proper sense of the word, rather it is incremental growth. This is why the same discovery can often be made simultaneously in different countries by different individuals. Often an important discovery happens before the world is ready to accept it and the unfortunate discoverer realizes that it is just as frustrating to be ahead of one’s times as it is to be behind the times.”

The reason why the parathyroids were discovered by several different scientists around 1880 was most probably related to the increased use of microscopes to describe normal and abnormally mutated cells and cell formations. The Dutch linen merchant Anton van Leeuwenhoek is credited with being the father of the microscope. He built a simple one-lensed microscope at the end of the 17th century and developed techniques for directing the light and improving the quality of lenses. In the mid-19th century, a microscope objective consisting of several weak lenses was developed and provided a sharper image and greater magnification by reducing the spherical aberrations (the chromatic effect) of light. The Zeiss optical company in Jena, Germany, developed mathematical formulas that offered the possibility of increased illumination, and the invention of the electric light further increased the technical potential. This development created the prerequisites for a new and previously unknown world – the world of microorganisms and cells. The German pathologists, especially Virchow, shifted the interest away from the organ to the cell.

Sandström had a great deal of experience with microscopic examinations, and for several years he was responsible for the microscopic laboratory exercises offered to the medical students. One of Sandström’s colleagues in the Anatomy Department, August Hammar, recalled that Sandström made his discovery during a microscopic examination of the thyroid of a dog. Thus it seems that he came upon the parathyroids via the microscope rather than on the dissecting table. The fact that electric light did not exist in Uppsala at the time of his discovery also suggests that Sandström did not initially see the gland during dissection – to be able to see a parathyroid gland in situ requires lighting that was hardly possible to achieve at that time. When Sandström realised that what he saw in the microscope was a new cellular structure he immediately ran to Professor Clason’s room with his specimen. The professor was not there but Sandström caught sight of the microscope in the room. He was taken aback when he saw a slide with cells of similar appearance under Clason’s microscope. At that instant, Clason appeared and Sandström wondered whether the professor had already seen what he wanted to show him. This was not the case, for Clason had in his microscope a slide specimen of cells from a pituitary gland – an organ which, with the deficiencies in histological staining techniques of those days, had a cellular structure very similar to that of the parathyroid gland. Today Sandström is most known as an anatomist; however his histological knowledge of the microscopic images of tissues and cells paved the way for his discovery. Sandström should therefore be considered outstanding both as a histologist and as an anatomist.

Sandström’s discovery of the parathyroids was based upon the fact that he continued with studies on other animals and humans as a result of his first observations in dogs; and also that he systematically and carefully described both the microscopic image and the location of the glands and thus could establish that he had actually discovered a new organ. Even though others had observed the parathyroids before Sandström, they had not followed up on their observations nor had they understood that they were dealing with a novel organ. For this reason, Sandström has to be considered the person who discovered the parathyroids. Referring to Sandström’s work, D. A. Welsh wrote:

“I cannot too strongly emphasise the admirable precision and accuracy which characterise this earliest record of these glands in man.”

While Sandström is arguably the first person to describe the parathyroids in humans, it turns out they had been observed earlier in a somewhat unlikely animal. In 1905, S.G. Shattock published a report which clarified that the parathyroids had in fact been observed prior to Sandström’s discovery in the one-horned Indian rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis). Before 1830 there were only a very few single-horned Indian rhinoceros that had survived more than a few years in captivity. Clara was a spectacular exception. In 1738 this rhinoceros calf was captured when she was only a few months old after her mother had been killed by Indian hunters. Soon Clara was purchased by the Dutch sea captain Douwe Mout van der Meer who shipped the young rhinoceros to Holland. Clara became used to humans early on and she developed a taste for tobacco and beer, probably as a result of misdirected kindness on the part of the Dutch sailors. The creative van der Meer organised a travelling menagerie where Clara was transported around Europe on an enormous cart pulled by eight horses. The project was an economic success and Clara was on exhibition for over seventeen years in many different places throughout central Europe, admired by both ordinary people and high society including Frederick the Great and Louis XV. Clara became the source of inspiration for poems and musical compositions, and was immortalised in paintings, copper engravings, and on medallions and porcelain. Clara was a true celebrity. Jan Wande...