eBook - ePub

A Companion to Greek Art

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Companion to Greek Art

About this book

A comprehensive, authoritative account of the development Greek Art through the 1st millennium BC.

- An invaluable resource for scholars dealing with the art, material culture and history of the post-classical world

- Includes voices from such diverse fields as art history, classical studies, and archaeology and offers a diversity of views to the topic

- Features an innovative group of chapters dealing with the reception of Greek art from the Middle Ages to the present

- Includes chapters on Chronology and Topography, as well as Workshops and Technology

- Includes four major sections: Forms, Times and Places; Contacts and Colonies; Images and Meanings; Greek Art: Ancient to Antique

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Companion to Greek Art by Tyler Jo Smith, Dimitris Plantzos, Tyler Jo Smith,Dimitris Plantzos in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Ancient Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1

The Greeks and their Art

We start from the purpose of the Greek artist to produce a statue, or to paint a scene of Greek mythology. Whence this purpose came, we cannot always see. It may have come […] from a commercial demand, or from a desire to exercise talent, or from a wish to honour the gods (Gardner 1914: 2).

1.1 Greek Art and Classical Archaeology

When Percy Gardner was appointed the first Lincoln and Merton Professor of Classical Archaeology at Oxford in 1887, the discipline was still largely in its infancy. His book entitled The Principles of Greek Art, written almost 100 years ago, demonstrates that classical archaeology of the day was as much about beautiful objects and matters of style as it was about excavation and data recording. Now, as then, the terms ‘Greek art’, ‘classical art’, and indeed ‘classical archaeology’ are somewhat interchangeable (Walter 2006: 4–7). To many ears the term ‘classical’ simply equals Greek – especially the visual and material cultures of 5th and 4th c. BC Athens. Yet it should go without saying, in this day and age, that Greek art is no longer as rigidly categorized or as superficially understood as it was in the 18th, 19th, and much of the 20th c. By Gardner’s own day, the picture was already starting to change. Classical archaeology, with Greek art at the helm, was coming into its own. The reverence with which all things ‘classical’ were once held – be they art or architecture, poetry or philosophy – would eventually cease to exist with the same intensity in the modern 21st c. imagination. At the same time, there would always be ample space for some old-fashioned formal analysis, and the occasional foray into connoisseurship.

Greek art has been defined in various ways, by various people, at various times. Traditionally, it has been divided into broad time periods (Orientalizing, Archaic, Classical, etc.) dependent on style and somewhat on historical circumstances or perceived cultural shifts. As with most areas of the discipline, this rather basic framework has seen a number of versions and has encouraged further (sometimes mind-numbingly minute) sub-categorization. In fact, no chronology of the subject has been universally accepted or considered to be exact. Some (though by no means all) speak in terms of the Late Archaic, High Classical, or Hellenistic Baroque; others prefer the Early Iron Age or the 8th c. BC (Whitley 2001: ch. 4). Regardless of terminology, within these large chronological divisions the subject has routinely been taught, discussed, and researched according to a triumvirate much loved by the history of art: sculpture, architecture, and painting (normally including vases); and leaving much of the rest relegated to the ill-defined catch-all phrase of ‘minor arts’ (Kleinkunst): terracottas, bronze figurines, gems and jewelry, and so on.

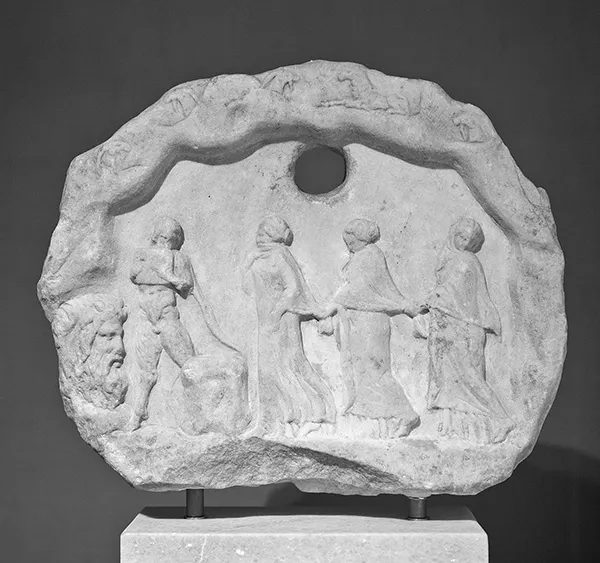

But major versus minor is not the whole story. Some areas of Greek art have proved more difficult to assemble than others. For example, should mosaics be placed under architecture, viewed in relation to wall-painting, or, for lack of a better option, classified as ‘minor’ art despite their sometimes vast scale? Other objects, such as coins, have not always been considered ‘art’ per se, in spite of their stylistic and iconographic similarities with other artifacts, and their sometimes critical role in the dating of archaeological contexts. Alas, it is a hierarchy that we have all come to live with for better or worse. It encourages questions of quality, taste, and value, and these days even plays a role in debates over cultural property and the repatriation of antiquities. Did all objects of ancient Greek art have ‘equal’ value? How might such value be measured? Should we even try? Is it valid to speak of earrings and fibulae in the same breath as Skopas and Mnesikles? Is a Boeotian ‘bell-idol’ as much a ‘work of art’ as a life-size sculpture, or a mold-made Megarian bowl (Figure 1.1) as worthy of our attention as an Athenian red-figure vase? Where, if at all, shall we draw the line? Do altars, votive reliefs (Figure 1.2), and perirrhanteria make the A-list? What about roof tiles and gutters; or, indeed, the ‘lost’ arts of weaving and basketry? Is it simply the inclusion of figure decoration, both mythological and everyday, on such ritual or utilitarian objects that allows them to join the corpus? Surely, the answer must lie somewhere between design and function, material and process. It is reassuring to think that any of the above might constitute ‘Greek art’, from the stately, good, and beautiful to the mundane, lewd, and grotesque.

Figure 1.1 Megarian bowl from Thebes. Scenes of the Underworld. c. 200 BC (London, British Museum 1897.0317.3. © The Trustees of the British Museum).

Figure 1.2 Attic marble votive relief from Eleusis. Cave of Pan . 4th c. BC (Athens, National Museum 1445. Photo: Studio Kontos/Photostock).

The function and context of ancient objects and monuments are crucial elements in the story of Greek art, and they place our subject on firm archaeological footing. The Greeks made little if any ‘art for art’s sake’. Even their most profound and aesthetically pleasing examples served a utilitarian purpose. Sanctuaries have produced abundant material remains, in some instances resulting from years of excavation. It is also worth noting that at many locations around the Greek world, evidence of the ancient built environment has been (more or less) visible, above ground, since antiquity. Panhellenic sites on the Greek mainland, such as Delphi and Olympia, fall firmly into this category. They have yielded everything from monumental architectural structures to large-scale stone sculptures, to bronze figurines, tripods, armor, and other objects suitable for votive dedication to the divine. Less well-known sanctuaries, such as the Boeotian Ptoon, have contributed a large number of Archaic kouroi. At Lokroi in southern Italy, a unique cache of terracotta votive plaques has been uncovered at the sanctuary of Demeter and Kore. The Heraion on Samos and the sanctuary of Artemis Orthia at Sparta have preserved rare examples of carving on ivory and bone, and in the case of the latter, thousands of tiny lead figurines in the form of gods, goddesses, warriors (Figure 1.3), dancers, musicians, and animals. Cemeteries and tombs located all around the Greek world have been equally important in preserving visual and material culture. In addition to informing us about burial customs, demography, and prestige goods, the necropoleis of the Kerameikos in Athens have been the single most important source for Geometric pottery (e.g. Figure 3.2), and the painted tombs at Vergina (Figure 8.4; Plate 8) the best surviving evidence for wall-painting of any period. Arguably, most of our current knowledge about Boeotian black-figure vases (e.g. Figure 4.3) stems from the excavations of the graves at Rhitsona conducted by P.N. and A.D. Ure early in the 20th c. The ongoing exploration of many sites confirms their importance as producers or consumers (or both) of ancient Greek art and architecture, and through this lens continues to advance our knowledge of society, religion, the economy, and so on. For example, Miletos in Ionia has been confirmed as an important center for the production of East Greek Fikellura vases (Cook and Dupont 1998: 77–89; Figure 4.9); Morgantina in central Sicily gives us the earliest known tessellated mosaic (Bell 2011); and Berezan (ancient Borysthenes), a small island on the north coast of the Black Sea, offers an excellent case study of Greek interaction with the nearby (Scythian) population through a combination of domestic dwellings, pottery styles, and burial methods (Solovyov 1999).

Figure 1.3 Lakonian lead figurine of a warrior, from Sparta. 6th–5th c. BC (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of A.J.B. Wace, 1924 (24.195.64). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence).

In recent year there has been a surge of publications designed to address the ‘state of the discipline’ and, in some cases, to challenge the ‘classical’ status quo (cf. Dyson 1993; Osborne 2004; Oakley 2009). Others, including articles, books, and conference volumes, have attempted whole-heartedly to thrust Greek art and classical archaeology into the 21st c., bringing in methods and ideas more at home in the (frankly, more progressive) disciplines of anthropology or art history (e.g. Donohue 2005; Stansbury-O’Donnell 2006; Schmidt and Oakley 2009), on the one hand, and cultural history or reception studies on the other (e.g. Beard 2003; Kurtz 2004; Prettejohn 2006). Their authors have represented various ‘schools’ or approaches, among them Cambridge, Oxford, continental Europe, and the United States (Meyer and Lendon 2005). Such daring, which is commonplace in most scholarly fields, might be met with suspicion amongst a classics establishment still grappling with issues such as the relationship between art, literature, and history, or the question of ‘lost originals’ that might unlock the mysteries of the great artistic masters once and for all. It is satisfying to think that we are still quite a long way from having heard the last word about ancient Greek art.

There are two further issues that should be addressed by way of introduction. Though seemingly quite different, they are each related to the study of Greek art and, in turn, to one another: (classical) text and (archaeological) theory. As a sub-field of classics, classical archaeology and thus the study of Greek art has been forever dependent on a good knowledge of Greek and Latin languages and literature (Morris 1994). Alongside this has come the expectation of using that knowledge to inform the objects and monument themselves, and to read the archaeological record. Thus, we would rarely, if ever, speak of the Athena Parthenos, a gold and ivory cult statue designed by the sculptor Pheidias, without referencing Pliny or Pausanias, or of the Athenian red-figure hydria in Munich portraying the Sack of Troy (Ilioupersis) without mentioning Homer or Vergil (Boardman 2001a: fig. 121). Since the time of Heinrich Schliemann and Sir Arthur Evans, such authoritative ancient texts have confirmed the existence and location of ancient places, and inspired the discovery of new ones. But these days the classical texts no longer uphold the unchallenged authority they once did (Stray 1998; Gill 2011), and classical archaeologists are increasingly following the lead of others, albeit slowly, in applying more scientific rigor and theoretical questioning to the process of exploration, recording, and the presentation of information. Theory, the stuff of ‘other’ disciplines, has not readily been accepted or welcomed, however, by Greek art’s ‘armchair’ archaeologists, who for generations have relied more heavily on their training in classics, and in fact viewed it as both a backdrop and a necessity. Such disconnect between the various parties involved culminated a few years back in a healthy debate between two scholars (both of whom appear in this Companion!) regarding the contribution of Sir John Beazley (1885–1970), the renowned expert on Greek vase-painting, initiated by an article entitled, ironically, ‘Beazley as Theorist’ (Whitley 1997; Oakley 1998). But as the current volume makes perfectly clear, Greek art cannot and should not be tackled in a uniform manner, and there remains ample room for a number of approaches, both old and new. There is legitimate space for multiple views. Indeed, a Companion such as this one combines the state of our knowledge with the state of our interests.

1.2 Greek Art after the Greeks

What then is ‘Greek’ about Greek art? And how much of it is ‘art’? For the Greeks, ‘art’ (techne) was craft and artists (demiourgoi) were by and large thought of as artisans: good with their hands and not much else (though famous ones, like Pheidias, came to be respected for their political power and the money that it made them). As many of the contributors to this publication explain (chiefly in Chapters 31–35 and 37), much of what we appreciate as ‘Greek art’ today, or have done so in the past, has been elaborated, embellished, and reinvented. In short, it has been translated by the crucial intervention of Rome and the Middle Ages, not to mention the systematic efforts of Western European elites in early modernity.

Not that this makes Greek art less ‘authentic’ or less ‘significant’ than it ought to be. As a cultural phenomenon, the arts of ancient Greece deserve our attention today perhaps more than ever, since we now know that an Archaic kouros or a scrap of the Parthenon marbles can carry much more than the sensibilities of their own era. As the Renaissance was gradually discovering the thrills of classical antiquity (Trigger 1989: 27–72; Shanks 1996), and as German intellectuals and Victorian aesthetes were struggling to decipher ‘the glory that was Greece’ (Jenkyns 1980; Eisner 1993; Marchand 1996), new cultural strategies regarding the conquest of the past were beginning to unfold. Familiarizing oneself with Greek and Roman art meant appropriating classical culture at large and, for the Western privileged class, this proved a commodity they could not resist. Bringing the Parthenon marbles ‘home’ to England in the early 19th c., for example, was much more than a case of treasure hunting (though Lord Elgin may have hoped for a good return on his investment when he sold the marbles to the British Museum in 1817). Turning the ‘Parthenon’ marbles into the world-renowned ‘Elgin’ marbles brought Western artists and intellectuals face to face with what original Greek art really looked like, an honor some of classical archaeology’s eminent forefathers had not lived long enough to know. The idea that, in a matter of years, a copy of the Parthenon frieze would adorn Hyde Park Gate in London (Figure 1.4), complete with a true-to-form Ionic colonnade, suggested that the ‘Greek revival’ was more than a feeble whim of the upper classes, wishing to embellish their country estates with quasi-Grecian charm. It was a strong intellectual movement. In effect, Greek art was becoming the modern signature of the West.

Figure 1.4 London, Hyde Park Gate, designed by Decimus Burton with a free version of the Parthenon frieze designed by John Henning, 1825 (photo: D. Plantzos).

Meanwhile, back in Greece, a tempestuous War of Independence (beginning in 1821), fueled by the ideological and material support of Romantic Philhellenism (as Decimus Burton was putting the final touches to Hyde Park Gate, Lord Byron lay dying in Missolonghi), gave birth to a fledglin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- List of Illustrations

- List of Color Plates

- List of Maps

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface

- PART I: Introduction

- PART II: Forms, Times, and Places

- PART III: Contacts and Colonies

- Series page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- List of Illustrations

- Notes on Contributors

- PART IV: Images and Meanings

- PART V: Greek Art: Ancient to Antique

- Bibliography

- Plates

- Index