eBook - ePub

Change Leadership

A Practical Guide to Transforming Our Schools

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Change Leadership

A Practical Guide to Transforming Our Schools

About this book

The Change Leadership Group at the Harvard School of Education has, through its work with educators, developed a thoughtful approach to the transformation of schools in the face of increasing demands for accountability. This book brings the work of the Change Leadership Group to a broader audience, providing a framework to analyze the work of school change and exercises that guide educators through the development of their practice as agents of change. It exemplifies a new and powerful approach to leadership in schools.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Change Leadership by Tony Wagner,Robert Kegan,Lisa Laskow Lahey,Richard W. Lemons,Jude Garnier,Deborah Helsing,Annie Howell,Harriette Thurber Rasmussen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Leadership in Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Introduction: Reframing the Problem

Our education system was never designed to deliver the kind of results we now need to equip students for today’s world—and tomorrow’s. The system was originally created for a very different world. To respond appropriately, we need to rethink and redesign.

In 1983 a government-appointed, blue-ribbon commission published a report entitled A Nation at Risk proclaiming a “crisis” in American public education. It described a “rising tide of mediocrity” in our country’s public schools. It argued that America’s economic security was threatened by a low-skill labor force that was no longer competitive in the global marketplace. The report launched a heated debate, inspiring three national summits on education where many of the nation’s governors and business leaders met to discuss the education crisis. A bipartisan national consensus on the importance of ensuring that all students have access to quality schools and a rigorous academic program began to emerge, as did a host of new initiatives and reforms at the local, state, and national levels. By the early 1990s, “education reform” had become the top priority for state governments. And in 2001, with the passage of No Child Left Behind legislation, the federal government assumed unprecedented authority over our nation’s public schools.

What has been the result of these efforts thus far? Data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) tests suggest some progress in raising students’ math scores at all grade levels in the last dozen years. However, the data on our accomplishments in reading and writing are very sobering. A long-term analysis of the average reading scores of both elementary and secondary school–age students shows virtually no change since 1980.1 And although writing scores increased slightly for fourth and eighth graders, the percentage of twelfth graders who scored “below basic” increased from 22 to 26 percent!2 More disturbing still are the data about the percentage of students who graduate from high school, the percentage of those who graduate “college-ready,” and the persistent gaps in achievement among different ethnic groups. According to recent research conducted by Jay Greene and Greg Forster at the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, in 2001 only about 70 percent of all high school students who started ninth grade in public schools actually graduated—a figure substantially lower than what has been assumed in the past and well below the graduation rates of half a dozen other industrialized countries. The graduation rate for Asian students was 79 percent; for white students, 72 percent; but barely 50 percent of all black and Latino students left high school with a diploma. Further, those who do finish high school are not necessarily college-ready. Only a little over a third of white and Asian students complete the necessary college preparation classes and possess the literacy skills required for success in college. Only 20 percent of black high school students and 16 percent of Latino students meet these qualifications.3

Do you know how the figures for your district stack up in comparison?

We find that many educators do not know the cohort graduation rates for their districts, perhaps for understandable reasons. Nonetheless, we think it is important that you be familiar with these numbers and how they compare with the national figures.

- How many students who begin ninth grade graduate within four years?

- How does your graduation rate for white and Asian students compare with that for black and Latino students?

- Do your graduation requirements match the entrance requirements for college in your state?

What you may well be pondering is this: Why has there been so little progress, despite all the good intentions and hard work of talented people, not to mention significant expenditures of time and money? It is our view that the “failure” of education reform efforts in the past twenty years is primarily the result of a misunderstanding of the true nature of the education “problem” we face. We focus here on the problem because, as Einstein reminds us, “The formulation of the problem is often more essential than its solution.”4 As we see it, the problem is less about a “rising tide of mediocrity” than about a tidal wave of profound and rapid economic and social changes, which we believe are not well understood by many educators, parents, and community members.

Misunderstanding the problem has, in turn, led to the selection of strategies at the national, state, and local levels that have not met the challenge head-on. To extend the analogy, we have been using gradualist strategies to solve the “slow-moving” problem of a “rising tide” when what is called for is a set of more dramatic and systemic interventions commensurate with the challenge of a tidal wave. The purpose of this chapter, then, is to reframe the education challenge so as to create a different understanding of the nature and range of solutions that are required for real results.5

A KNOWLEDGE ECONOMY REQUIRES NEW SKILLS FOR ALL STUDENTS

In the 1970s, our graduation and college-readiness rates were even lower than they are today, but this was not considered a “crisis.” It has become a crisis because of the nature of the skills needed in today’s knowledge economy. Our economy has transitioned from one in which most people earned their living with skilled hands to one in which all employees need to be intellectually skilled if they hope to make more than minimum wage. In nearly every industry today, companies are hiring the most highly educated people they can find or afford. For the past decade, CEOs like David Kearns (Winning the Brain Race) and academics like Richard Murnane and Frank Levy (Teaching the New Basic Skills and The New Division of Labor) have described the significant competitive advantages of a highly educated labor force.6 Employees must know how to solve more complex problems more quickly, and must create new goods and services if they are to add significant value to virtually any business or nonprofit organization, no matter what size. And those who don’t have these skills are not being hired.7

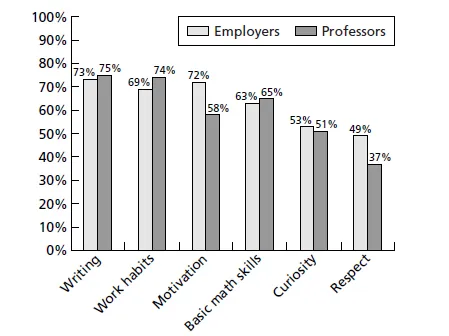

Because this change came so quickly, many people are surprised to learn that the skills required in most workplaces today directly correspond to those that are needed for success in college. Although not all young people need to have a college education to get a decent job, employers are increasingly expecting that new employees will have skills comparable to students who do attend college. Figure 1.1, drawn from a 2002 Public Agenda Foundation study, shows the ranking of the skills and habits of mind in which high school graduates are least well prepared for work and college.8 Notice the agreement on the skills that employers and college professors now demand: writing, work habits, motivation, basic math skills, curiosity, respect. In light of this, the differences seem minor. For example, employers say that their new hires lack adequate skill in writing; college professors find that entering students do not write adequately. The difference is a mere 2 percent; even more striking is how high those percentages are: 73 and 75, respectively.

Figure 1.1 Percentage of Employers and Professors Saying High School Graduates are Unprepared

Reality Check © Public Agenda 2002. No reproduction/distribution without permission. www.publicagenda.org

The competencies that academics and business leaders now demand are not just “the basics—the 3 R’s.” When they talk about good writing skills, for example, both groups are associating effective writing with a person’s ability to reason, analyze, and hypothesize; find, assess, and apply relevant information to the solution of new problems; and, of course, write and speak clearly and concisely. All these, plus the ability to use a range of information and communication technologies, are the new literacy demands of a knowledge economy that go far beyond basic reading and writing skills. The math skills demanded, similarly, go beyond computation to include a working knowledge of statistics, probability, graphing, and spreadsheets. Finally, the expectation that young adults will come to college or the workplace knowing how to organize and motivate themselves to learn independently, do quality work, and team with others represents a shift toward the increasing importance of what Daniel Goleman calls emotional intelligence.9

In a new report written for the Educational Testing Service, Anthony P. Carnevale and Donna M. Desrochers summarize the key competencies needed by workers in today’s new economy:10

- Basic Skills: Reading, Writing, and Mathematics

- Foundation Skills: Knowing How to Learn

- Communication Skills: Listening and Oral Communication

- Adaptability: Creative Thinking and Problem Solving

- Group Effectiveness: Interpersonal skills, Negotiation, and Teamwork

- Influence: Organizational Effectiveness and Leadership

- Personal Management: Self-Esteem and Motivation/Goal Setting

- Attitude: Positive Cognitive Style

- Applied Skills: Occupational and Professional Competencies

The realities of today’s economy demand not only a new set of skills but also that they be acquired by all students.

So when studies reveal that the overwhelming majority of today’s public high school students leave school “unprepared for college,” they also indicate a lack of preparation to access most jobs in our economy and to assume responsible roles as informed citizens in a democracy. An eighteen-year-old who is not college-ready today has effectively been sentenced to a lifetime of marginal employment and second-class citizenship. The realities of today’s economy demand not only a new set of skills but also that they be acquired by all students.

Although this information may not be new to you as an education leader, evidence suggests that there is a serious “perception gap” between majorities of high school parents and teachers, on the one hand, and professors and employers on the other. According to a recent Public Agenda Foundation national survey, 67 percent of high school parents and 78 percent of high school teachers believe that public school graduates have “the skills needed to succeed in the work world.” However, only 41 percent of employers in the same survey thought that these graduates had what was needed to do well in the workplace.11 This finding suggests that the first task in a successful systemic change process is to generate greater understanding and urgency for change (which we discuss in Chapter Eight).

GREATER SUPPORTS FOR LEARNING IN A CHANGING SOCIETY

So we educators have a new challenge, one that could be considered both formidable and unprecedented in any context because we have not had to educate all students to this skill level before. But the problem we face extends even beyond the “all students, new skills” challenge. For when we ask teachers to name the greatest hurdles they face in classrooms, they talk most frequently about students who appear less motivated to learn traditional academic content and lack of family support for learning. More than eight out of ten teachers in a recent study cite as a serious problem “parents who fail to set limits and create structure at home for their kids and who refuse to hold their kids accountable for their behavior or academic performance.”12

Strikingly, in this same study, a majority of parents agreed they need to be doing more to ensure that their children do their best in school. Many parents also say that supporting their children’s learning is a significant challenge for which they feel largely unprepared. Despite the fact that more than 75 percent of all parents in one Public Agenda study reported being more involved in their children’s education than were their parents, less than one in four agreed that they “know a lot about how to motivate their own children.”13 In another recent Public Agenda study, more than 75 percent of the parents surveyed said that raising children is a lot harder today, compared with when they were growing up.14

These findings point to profound changes in our society that have significant impact on teaching and learning: today’s young people are growing up w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Chapter One: Introduction: Reframing the Problem

- Part One: Improving Instruction

- Part Two: Why is this so Hard?

- Part Three: Thinking Systemically

- Part Four: Working Strategically

- Appendixes

- Index