![]()

1.1 SURFACE ANALYSIS

We interact with our surroundings through our five senses: taste, touch, smell, hearing, and sight. The first three require signals to be transferred through some form of interface (our skin, taste buds, and/or smell receptors). An interface represents two distinct forms of matter that are in direct contact with each other. These may also be in the same or different phases (gas, liquid, or solid). How these distinct forms of matter interact depends on the physical properties of the layers in contact.

The physical properties of matter are defined in one form or another by the elements present (the types of atoms) and how these elements bond to each other (these are covered further in Section 2.1). The latter is referred to as speciation.

An example of speciation is aluminum (spelt aluminium outside the United States) present in the metal form versus aluminum present in the oxide form (Al2O3). In these cases, aluminum exists in two different oxidation states (Al0 vs. Al3+) with highly diverse properties. As an example, the former can be highly explosive when the powder form is dispersed in an oxidizing environment (this acted as a booster rocket propellant for the space shuttle when mixed with ammonium perchlorate), while the latter is extremely inert (this is the primary form aluminum exists within the earth’s crust).

Aluminum foil (the common household product) is primarily metallic. This, however, is completely inert to the environment (air under standard temperature and pressure) since it is covered by a thin oxide layer that naturally reforms when compromised. This layer is otherwise referred to as a passivating oxide. Note: Aluminum metal does not occur naturally. This is a man-made product whose cost of manufacture has decreased dramatically over the last 200 years. Indeed, aluminum metal was once considered more precious than gold, and it is reputed that Napoleon III honored his favored guests by providing them with aluminum cutlery with the less favored guests being provided with gold cutlery.

Like aluminum foil, most forms of matter present in the solid or liquid phase exhibit a surface layer that is different from that of the underlying material. This difference could be chemical (composition and/or speciation), structural (differences in bond angles or bond lengths), or both. How a material is perceived by the outside world thus depends on the form of the outer layer (cf. an object’s skin or shell). The underlying material is referred to as the bulk throughout the remainder of this text. Also, gases are not considered due to their high permeability, a fact resulting from a lack of intermolecular forces and the high velocity of the constituents (N2 and O2 in air travel on average close to 500 m/s, with any subsequent collisions defining pressure).

Reasons as to why the physical properties of a solid or liquid surface may vary from the underlying bulk can be subdivided into two categories, these being

(a) External Forces (i.e., Adsorption and/or Corrosion of the Outer Surface). Pieces of aluminum or silicon are two examples in which a stable oxide (passivation layer) is formed on the outer surface that is only a few atomic layers thick (∼1 nm). Note: Air is a reactive medium. Indeed, water vapor catalyzes the adsorption of CO2 on many metallic surfaces (both water vapor and CO2 are present in air), and so forth.

(b) Internal Forces (i.e., Those Relayed through Surface Free Energy). These are introduced by the abrupt termination of any long-range atomic structure present and can induce such effects as elemental segregation, structural modification (relaxation and/or reconstruction), and so on. This too may only influence the outer few atomic layers.

Some of the physical properties (listed in alphabetical order) that can be affected as a result of these modifications (notable overlaps existing between these) include

(a) Adhesion

(b) Adsorption

(c) Biocompatibility

(d) Corrosion

(e) Desorption

(f) Interfacial electrical properties

(g) Reactivity inclusive of heterogeneous catalysis

(h) Texture

(i) Visible properties

(j) Wear and tear (also referred to as tribology)

(k) Wetability, and so on

If the surface composition and speciation can be characterized, the manner in which the respective solid or liquid interacts with its surroundings can more effectively be understood. This, then, introduces the possibility of modifying (tailoring) these properties as desired. From a technological standpoint, this has resulted in numerous breakthroughs in almost every area in which surfaces play a role. Some areas (listed in alphabetical order) in which such modifications have been applied include

(a) Adhesion research

(b) Automotive industry

(c) Biosciences

(d) Electronics industry

(e) Energy industry

(f) Medical industry

(g) Metallurgy industry inclusive of corrosion prevention

(h) Pharmaceutical industry

(i) Polymer research, and so on

Indeed, many of these breakthroughs have resulted from the tailoring of specific surface properties and/or the formulation of new materials that did not previously exist in nature. Like aluminum foil, these are all man-made with examples ranging from the development of plastics to synthesis of superconducting oxides, and so on.

A solid or liquid’s surface can be defined in several different ways. The more obvious definition is that a surface represents the outer or topmost boundary of an object. When getting down to the atomic level, however, the term boundary loses its definition since the orbits of bound electrons are highly diffuse. An alternative definition would then be that a surface is the region that dictates how the solid or liquid interacts with its surroundings. Applying this definition, a surface can span as little as one atomic layer (0.1–0.3 nm) to many hundreds of atomic layers (100 nm or more) depending on the material, its environment, and the property of interest.

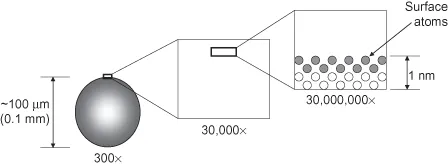

To put these dimensions into perspective, consider a strand of human hair. This measures between 50 and 100 µm (0.05–0.1 mm) in diameter. The atoms making up the outer surface are of the order of 0.2 nm in diameter. This cannot be viewed even under the most specialized optical microscope (typical magnification is up to ∼300×) since the spatial resolution is diffraction limited to values slightly less than 1 µm (see Appendix E). The magnification needed (∼30,000,000×) can only be reached using a very limited number of techniques, with the most common being transmission electron microscopy (TEM). These concepts are illustrated in Figure 1.1.

TEM being a microscopy, however, only reveals the physical structure of the object in question. To reveal the chemistry requires spectroscopy or spectrometry (the original difference in terminology is discussed in Appendix F). Although a plethora of spectroscopies and spectrometries exists, few are capable of providing the chemistry active over the outermost surface, that is, that within the outermost 10 nm of a solid. Of the few available, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), also referred to as electron spectroscopy for chemical analysis (ESCA), has over the last several decades become the most popular. Some comparable/complementary microanalytical techniques are discussed in Appendices F and G.

1.2 XPS/ESCA FOR SURFACE ANALYSIS

XPS, also referred to as ESCA, represents the most heavily used of the electron spectroscopies (those that sample the electron emissions) for defining the elemental composition of a solid’s outer surface (within the first 10 nm). The acronym XPS will be used henceforth in this text since this more precisely describes the technique. The acronym ESCA was initially suggested by Kai Siegbahn when realizing that speciation could be derived from the photoelectron and Auger electron emissions alone.

The popularity of XPS stems from its ability to

(a) Identify and quantify the elemental composition of the outer 10 nm or less of any solid surface with all elements from Li–U detectable. Note: This is on the assumption that the element of interest exists at >0.05 atomic % (H and He are not detectable due to their extremely low photoelectron cross sections and the fact that XPS is optimized to analyze core electrons).

(b) Reveal the chemical environment where the respective element exists in, that is, the speciation of the respective elements observed.

(c) Obtain the above information with relative ease and minimal sample preparation.

Aside from ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS), which can be thought of as an extension of XPS since this measures the valence band photoelectrons, Auger electron spectroscopy (AES) is the most closely related technique to XPS in that it displays a similar surface specificity while being sensitive to the same elements (Li–U). Its strength lies in its improved spatial resolution, albeit at the cost of sensitivity (for further comparisons of related techniques, see Appendix F).

Wavelength-dispersive X-ray analysis (WDX) and energy-dispersive X-ray analysis (EDS or EDX) are also effective for defining the elemental composition of solids. Indeed, when combined with scanning electron microscopy (SEM), these are more popular than XPS, with the moniker electron probe microanalysis (EPMA) often used. These, however, are not considered true surface analytical techniques, at least not in the strict sense, since they provide avera...