![]()

1

The Evolution of Six Sigma, Lean Sigma and FIT SIGMATM

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Today, depending on whom you listen to, Six Sigma is either a revolution slashing trillions of dollars from Corporate inefficiency, or it's the most maddening management fad yet devised to keep front-line workers too busy collecting data to do their jobs.

USA Today, 21 July 1998

At the time of writing, it has been 12 years since the above statement was made. During this time the ‘Six Sigma revolution’ has created a huge impact in the field of operational excellence, yet conflicting views are still prevalent.

Let us evaluate the arguments for both sides. On a positive note, the success of ‘Six Sigma’ in General Electric (GE) under the leadership of Jack Welch is undisputed. In the GE company report of 2000, their CEO was unstinting in his praise: ‘Six Sigma has galvanised our company with an intensity the likes of which I have never seen in my 40 years at GE.’ Even financial analysts and investment bankers compliment the success of Six Sigma at GE. An analyst at Morgan Stanley Dean Witter recently estimated that GE's gross annual benefit from Six Sigma could reach 5% of sales and that share values might increase by between 10% and 15%.

However, the situation is more complex than such predictions would suggest. In spite of the demonstrated benefits of many improvement techniques such as total quality management (TQM), business process re-engineering and Six Sigma, most attempts by companies to use them have ended in failure (Easton and Jarrell, 1998). Sterman et al. (1997) conclude that companies have found it extremely difficult to sustain even initially successful process improvement initiatives. Yet more puzzling is the fact that successful improvement programmes have sometimes led to declining business performance, causing lay-offs and low employee morale. Motorola, the originator of Six Sigma, announced in 1998 that its second-quarter profit was almost non-existent and that consequently it was cutting 15,000 of its 150,000 jobs.

To counter heavyweight enthusiasts like Jack Welch (GE) and Larry Bossidy (Allied Signal), there are sharp critics of Six Sigma. In fact, Six Sigma may sound new, but critics say that it is really just statistical process control in new clothing. Others dismiss it as another transitory management fad that will soon pass.

It is evident that like any good product, Six Sigma should also have a finite life cycle. In addition, business managers can be forgiven if they are often confused by the grey areas of distinction between quality initiatives such as TQM, Six Sigma and Lean Sigma.

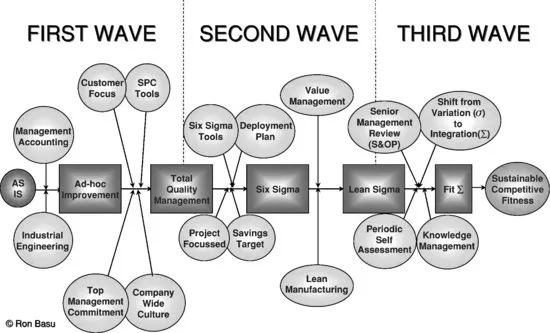

Against this background, let us examine the evolution of total quality improvement processes (or in a broader sense, operational excellence) from ad-hoc upgrading, working up to TQM and then to Six Sigma and finally to Lean Sigma. Building on the success factors of these processes, the vital question is: how do we sustain the results? The author has named this sustainable process FIT SIGMATM (see Basu and Wright, 2003).

So, what is FIT SIGMA? Firstly, take the key ingredient of quality, then add accuracy in the order of 3.4 defects in 1,000,000. Now implement this across your business with an intensive education and training programme. The result is Six Sigma. Now let's look at Lean Enterprise, an updated version of classical industrial engineering. It focuses on delivered value from a customer's perspective and strives to eliminate all non-value-added activities (‘waste’) for each product or service along a value chain. The integration of the complementary approaches of Six Sigma and Lean Enterprise is known as Lean Sigma. FIT SIGMA is simply the next wave. If Lean Sigma provides agility and efficiency, then FIT SIGMA allows a sustainable fitness. In addition, the control of variation from the mean (small sigma ‘σ’) in the Six Sigma process is transformed to company-wide integration (capital Sigma ‘Σ’) in the FIT SIGMA process. Furthermore, the philosophy of FIT SIGMA should ensure that it is indeed fit for the organisation.

The road map to FIT SIGMA (see Figure 1.1) contains three waves and the entry point of each organisation will vary:

- First Wave: As is to TQM.

- Second Wave: TQM to Lean Sigma.

- Third Wave: Lean Sigma to FIT SIGMA.

1.2 FIRST WAVE: AS IS TO TQM

The organised division of labour to improve operations may have started with Adam Smith in 1776. However, it is often the industrial engineering approach, which has roots in F.W. Taylor's ‘Scientific Management’, that is credited with the formal initiation of the first wave of operational excellence. This industrial engineering approach was sharpened by operational research and complemented by operational tools such as management accounting.

During the years following the Second World War, the ‘First Wave’ saw through the rapid growth of industrialisation; but in the short term the focus seemed to be upon both increasing volume and reducing the cost. In general, improvement processes were ‘ad-hoc’, factory-centric and conducive to ‘pockets of excellence’. Then in the 1970s the holistic approach of TQM initiated the ‘Second Wave’ of operational excellence. The traditional factors of quality control and quality assurance are aimed at achieving an agreed and consistent level of quality. However, TQM goes far beyond mere conformity to standard. TQM is a company-wide programme and requires a culture in which every member of the organisation believes that not a single day should go by within that organisation without in some way improving the quality of its goods and services.

1.3 SECOND WAVE: TQM TO LEAN SIGMA

Learning the basics from W.E. Deming and J.M. Juran, Japanese companies extended and customised the integrated approach and culture of TQM (Basu and Wright, 1998; Oakland, 2003). Arguably, the economic growth and manufacturing dominance of Japanese industries in the 1980s can be attributed to the successful application of TQM in Japan. The three fundamental tenets of Juran's TQM process are firstly, upper management leadership of quality; secondly, continuous education on quality for all; and finally, an annual plan for quality improvement and cost reduction. These foundations are still valid today and embedded within the Six Sigma/Lean Sigma philosophies. Phil Crosby and other leading TQM consultants incorporated customer focus and Deming's SPC tools and propagated the TQM philosophy both to the USA and the industrialised world. The Malcolm Baldridge Quality Award, ISO 9000 and the Deming Quality Award have enhanced the popularity of TQM throughout the world, while in Europe the EFQM (European Foundation of Quality Management) was formed. During the 1980s, TQM seemed to be everywhere and some of its definitions – such as ‘fitness for the purpose’, ‘quality is what the customer wants’ and ‘getting it right first time’ – became so over-used that they were almost clichés. Thus the impact of TQM began to diminish.

In order to complement the gaps of TQM in specific areas of operation excellence, high-profile consultants marketed mostly Japanese practices in the form of a host of three-letter acronyms (TLAs), such as JIT, TPM, BPR and MRP(II). Total productive maintenance (TPM) has demonstrated successes outside Japan by focusing on increasing the capacity of individual processes. TQM was the buzzword of the 1980s but it is viewed by many, especially in the US quality field, as an embarrassing failure – a quality concept that promised more than it could deliver. Phil Crosby pinpoints the cause of TQM ‘failures’ as ‘TQM never did anything to define quality, which is conformance to standards’. Perhaps the pendulum swung too far towards the concept of quality as ‘goodness’ and the employee culture. It was against this background that the scene for Six Sigma appeared to establish itself.

Six Sigma began back in 1985 when Bill Smith, an engineer at Motorola, came up with the idea of inserting hard-nosed statistics into the blurred philosophy of quality. In statistical terms, sigma (σ) is a measure of variation from the mean; thus the greater the value of sigma, the fewer the defects. Most companies produce results which are at best around four sigma, or more than 6000 defects. By contrast, at the six sigma level, the expectation is only 3.4 defects per million as companies move towards this higher level of performance.

Although invented at Motorola, Six Sigma has been experimented with by Allied Signal and perfected at General Electric. Following the recent merger of these two companies, GE is truly the home of Six Sigma. During the last five years, Six Sigma has taken the quantum leap into operational excellence in many blue-chip companies including DuPont, Ratheon, Ivensys, Marconi, Bombardier Shorts, Seagate Technology and GlaxoSmithKline.

The key success factors differentiating Six Sigma from TQM are:

1. The emphasis on statistical science and measurement.

2. A rigorous and structured training deployment plan (Champion, Master Black Belt, Black Belt and Green Belt).

3. A project-focused approach with a single set of problem-solving techniques such as DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyse, Improve, Control).

4. Reinforcement of the Juran tenets (Top Management Leadership, Continuous Education and Annual Savings Plan).

Following their recent application in companies like GlaxoSmithKline, Ratheon, Ivensys and Seagate, the Six Sigma programmes have moved towards the Lean Sigma philosophy, which integrates Six Sigma with the complementary approach of Lean Enterprise. Lean focuses the company's resources and its suppliers on the delivered value from the customer's perspective. Lean Enterprise begins with Lean Production, the concept of waste reduction developed from industrial engineering principles and refined by Toyota. It expands upon these principles to engage all support partners and customers along the value stream. Common goals to both Six Sigma and Lean Sigma are the elimination of waste and the improvement of process capability. The industrial engineering tools of Lean Enterprise complement the science of the statistical processes of Six Sigma. It is the integration of these tools in Lean Sigma that provides an operational excellence methodology capable of addressing the entire value delivery system.

1.4 THIRD WAVE: LEAN SIGMA TO FIT SIGMA

Lean Sigma is the beginning of the ‘Third Wave’. The predictable Six Sigma precisions combined with the speed and agility of Lean produces definitive solutions for better, faster and cheaper business processes. Through the systematic identification and eradication of non-value-added activities, optimum value flow is achieved, cycle times are reduced and defects eliminated.

The dramatic bottom line results, and extensive training deployment of Six Sigma and Lean Sigma must be sustained with additional features for securing the longer-term competitive advantage of a company. The process to do just that is FIT SIGMA. The best practices of Six Sigma, Lean Sigma and other proven operational excellence best practices underpin the basic building blocks of FIT SIGMA.

Four additional features are embedded in the Lean Sigma philosophy to create FIT SIGMA. These are: