![]()

PART I

Europe

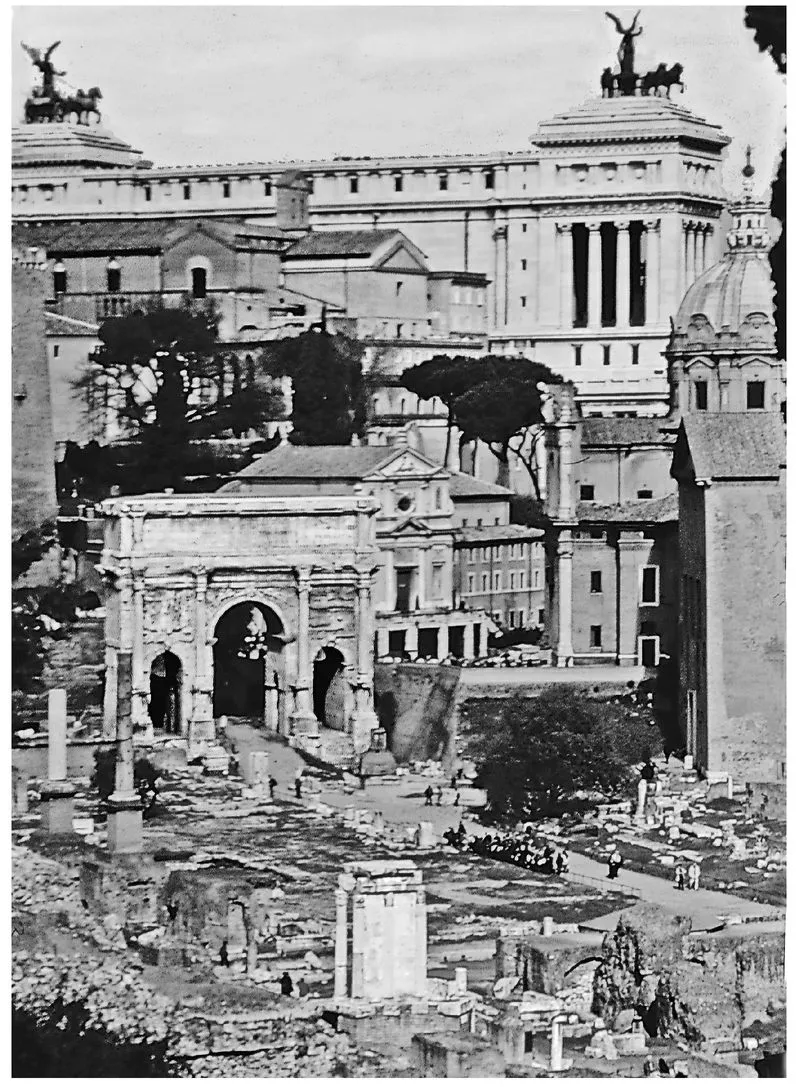

To mark the fiftieth anniversary of the formation of the Council of Europe as well as the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Council of Europe’s European Year for Cultural Heritage, a campaign to promote the natural and cultural heritage of Europe took place from late 1999 through the year 2000. The “Europe, A Common Heritage” campaign brought the twentieth century to a close: a century that is remembered in Europe for the destruction of the two world wars as well as for the historic buildings and environments preserved thanks to the maturation of the architectural conservation movement. The new millennium dawned in Europe with the recognition of escalating conservation challenges—such as pressures from economic development, tourism, and global warming—but also with unprecedented cooperation and coordination on behalf of cultural heritage across Europe.

Europe is a vast continent, a cultural sphere, and a political and economic union each with boundaries that differ and have shifted over time. In spite of diverse geographies, histories, cultures, and scales, today there is an ever-increasing unity of purpose and ideals within Europe and a shared concern for its architectural heritage. Europe stretches from the rolling Ural Mountains to the tip of Gibraltar on the Mediterranean Sea and from the expansive Caspian Sea to the fjords of Iceland. It includes countries that vary in area, population, climate, history, and culture ranging from the expansive Russian Federation to small Malta and Liechtenstein. Over the course of Europe’s history, the ties and relationships among its disparate parts have evolved, and peripheral countries have participated to varying degrees. Countries or regions with geographical or cultural affinities toward Europe that might not always be considered part of the region proper, such as Caucasia, Greenland, Siberia, and Anatolia, will be considered along with Europe for the purposes of this book.

Europe’s long and well-documented history led to an early appreciation of its cultural heritage, and as such, from a global perspective, it had an advanced start in architectural conservation practice. From the Renaissance’s critical approach to the past and the birth of antiquarianism, to the eighteenth century’s culture of rationalism, enlightenment, and international exploration, to the nineteenth century’s interest in heritage values and protection for the social good, Europe has been the place where the ideas that underlie contemporary cultural heritage conservation practice emerged. In Europe, the development of administrative mechanisms and legal structures for the identification, protection, and preservation of cultural heritage has a unique and long history, clearly discernable patterns, and, as elsewhere, a constantly expanding scope.

Many of the global architectural conservation movement’s principles and charters originated in Europe and it has always been a global leader in the field. Europe played an instrumental role in the establishment of two global cultural heritage protection institutions: the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). UNESCO was established in the wake of World War II as an intergovernmental organization aimed toward promotion of international dialogue, shared values, and respect for cultural diversity. In 1964 in Venice, at the Second Congress of Architects and Specialists of Historic Buildings, the International Restoration Charter, known as the Venice Charter, was signed, and ICOMOS was created as an international nongovernmental organization (NGO).1 Half of the countries represented (and 90 percent of the delegates) at that foundational meeting were European.

Today forty-seven European countries are member states of UNESCO, and there are ICOMOS national chapters in almost all of them. Europe is still disproportionately represented on UNESCO’s World Heritage List, with over half the inscribed cultural and mixed heritage sites found within its countries. Both UNESCO and ICOMOS are global in their scope, but the protective mechanisms and best practices they have developed—and the architectural conservation projects they have supported—have had a direct impact mainly on Europe.

Regional intergovernmental institutions such as the Council of Europe and the European Union (EU) have also played important roles in encouraging the sharing of experiences and expertise within Europe as well as the standardizing of policies and practices throughout the continent. The Council of Europe, founded in 1949 by ten countries, but today comprising forty-seven member states, has retained its original focus on promoting democracy, human rights, the rule of law, and European integration. The Council of Europe’s active interest in heritage protection began with the European Cultural Convention, signed in Paris in 1954 by fourteen countries to promote mutual understanding and reciprocal appreciation for each other’s cultures, as well as to protect their common heritage.2

To promote intergovernmental collaboration at the highest level, the Council of Europe has organized numerous Conferences of Ministers Responsible for the Cultural Heritage. At the first such conference, held in Brussels in 1969, discussions were initiated that eventually led to the European Charter of the Architectural Heritage that was signed as part of the activities of the Council of Europe’s European Year for Cultural Heritage in 1975.3 This charter’s goal was “to make the public more aware of the irreplaceable cultural, social and economic values” embodied in the diversity of its built heritage.4 The European Heritage Year program also encouraged local and national governments to actively inventory, protect, and rehabilitate their historic sites and to pay special attention to preventing insensitive changes to them.5

The 1975 charter led to the adoption in 1985 in Granada of the Convention for the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe; however, this was not the first legally binding convention developed through the initiative of the Council of Europe. Indeed, a supplement to the 1954 European Cultural Convention had previously been enhanced with a specific convention to protect European archaeological heritage: it was signed in 1969 in London, and was revised in 1992 in Valletta, Malta.6 In 2005 another convention (the Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society) was drafted by the Council of Europe in Faro, Portugal, and it will soon have been ratified by enough countries to enter into force.7 The various heritage charters and conventions and the European Year for Cultural Heritager laid the groundwork for coordinating conservation policies and fostering practical cooperation between government institutions and conservation professionals in Europe.

The European Union was formed in 1993; however, its executive body and predecessor, the European Commission, has been involved in cultural heritage programs almost since its inception in the 1950s. Today the EU includes twenty-seven member states, comprising most of Europe except for Norway, Switzerland, Iceland, Turkey, the Western Balkans, and some former states of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. In combination with other factors, the draw of membership to the EU has done much for the updating of heritage protection laws and the strengthening of relevant institutions throughout Central and Eastern Europe in the past decade. The EU’s member states are less numerous and geographical extent is much smaller than that of the Council of Europe, but because its members have surrendered some sovereignty to this supranational body, it has greater authority to enforce regulations and coordinate activities. Viewing heritage “as a vehicle for cultural identity” and “as a factor in economic development,” the EU has acted to promote awareness and access, the training of professionals, and the use of new technologies as well as to reduce the illicit trafficking in cultural objects.8

Through a collection of innovative interrelated programs the Council of Europe and the European Union have worked separately and collaboratively to promote cultural heritage concerns and a shared European identity. In 1985 the EU initiated its European Capital of Culture program, an idea that originated with the Greek Minister of Culture, Melina Mercouri, and led to the selection of Athens as the inaugural city for such international attention. Each year, one European city is honored and provided financial assistance to organize cultural heritage–related activities; however, in 2000, nine cites were designated in special recognition of the millennium, and since then pairs of cities have often shared the honor. Meant to highlight the diversity within Europe, promote tourism, and stimulate cultural initiatives in general, the program has encouraged the construction of elaborate new cultural facilities and significantly aided architectural and urban conservation efforts in many of the selected cities. According to the Palmer Report, issued by the European Commission in 2004 after a lengthy survey and evaluation of the program’s first two decades by an independent consultant, the European Capital of Culture program proved “a powerful tool for cultural development that operates on a scale that offers unprecedented opportunities for acting as a catalyst for city change.”9 However, the report also noted that though good for individual cities and local political agendas, the program could be more coordinated and more focused on the “European dimension” of that heritage. Nevertheless, the program’s success at spurring and popularizing conservation efforts in specific cities has led to its imitation beyond Europe: for example, since 1996, the Arab League has sponsored an Arab Capital of Culture program, and since 1997 the Organization of American States has designated an American Capital of Culture each year.

In 1991 the Council of Europe initiated its European Heritage Days program, which has been a joint venture with the EU’s European Commission since 1999. Through this program, each September, important but usually inaccessible historic sites are opened to the public, and other museums and historic sites offer special activities in a pan-European celebration of heritage. Most countries develop specific themes to link the sites included in a given year, and preparations have prompted the completion of countless restoration and conservation projects throughout Europe. Various local and international NGOs have also coordinated activities to participate in this month highlighting heritage throughout Europe.

In the past twenty-five years, the European Heritage Days program’s efforts have significantly raised public awareness for heritage and encouraged governments to prioritize this issue. In recent years, the focus of the European Heritage Days has shifted more and more to emphasize Europe’s shared heritage and identity to further promote European integration. According to the 2009 Handbook on European Heritage Days (published by the EU and the Council of Europe), today’s challenge is “to develop awareness of a common heritage, from Yerevan to Dublin and from Palermo to Helsinki, without negating the feeling of belonging to a specific region or country. In short, we must ensure that, in the words of Jean-Michel Leniaud, the European heritage is the combined expression of a search for diversity and a quest for unity.”10

Launched in 1999, the Council of Europe’s European Heritage Network (known as HEREIN) has served as a central reference point and resource for professionals, administrators, and researchers.11 Designed to create a forum for the coordination of activities of government departments responsible for heritage in various European countries, it has mostly focused on maintaining a database on the cultural policies of those countries and promoting the digitization of cultural and natural heritage information and materials and the standardization of heritage language. Since 2001 it has focused on eastward expansion and integration of Europe as well as on expanding its thesaurus of heritage terms to include as many European languages as possible.

Informal intergovernmental cooperation has also been organized in recent years through the European Heritage Heads Forum (EHHF), which brings the leaders of state heritage protection agencies together to share ideas and strategies.12 The first meeting was held in London in 2006 and proved so successful that it has been repeated annually. In 2007 a parallel European Heritage Legal Forum (EHLF) was formed by nineteen countries to research and monitor European Union legislation and its potential impact on...