eBook - ePub

The Manager's Guide to Systems Practice

Making Sense of Complex Problems

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Manager's Guide to Systems Practice

Making Sense of Complex Problems

About this book

This book is an ideal resource on the subject of systems practice for busy managers whose time is scarce. It provides a rapid introduction to straightforward, yet powerful ideas that enable users to address real world problems. Systems theory and practice is predominantly a framework for thinking about the World, in which holistic views are maintained. In this respect it contrasts with some familiar techniques of management science, in which problem situations are broken down into their constituent parts with resultant loss of coherence.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Manager's Guide to Systems Practice by Frank Stowell,Christine Welch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

KEY SYSTEMS IDEAS

KEY SYSTEMS IDEAS

Chapters 1, 2 and 3

The following three chapters are designed to introduce the learner to some simple yet powerful ideas. Following a short introduction to the ideas plus some exercises the ideas can be soon learnt and put into practice. Each chapter in this section contains self-assessment exercises and exercises that will help consolidate what has been learnt. It is worth pointing out that there are one-day workshops available, for example, those offered by the systems practice for managing complexity network (spmc) where opportunities are available to practise the ideas under the guidance of an experienced tutor. For more detail see http://www.northumbria.ac.uk/sd/academic/ceis/enterprise/spmc/

CHAPTER 1

Understanding Things: The Manager’s Guide to Systems Practice

Introducing Some Basic (But Powerful) Ideas

Begin at the Beginning – What is a System?

We encounter the word ‘system’ often in our daily lives. It crops up in many different contexts – some technical, some social and some philosophical. This text is for people who are intrigued by the concept of ‘Systems’ and want to clarify and develop understanding of its usefulness. In this text, we will explore use of the word ‘System’ and related terms such as ‘Systems Thinking’ and attempt to resolve some of the confusion surrounding these terms. As the chapters progress, we will introduce further aspects of Systems practice, and elaborate upon its usefulness in dealing with the challenges of life in the 21st century.

We will deal with the origin of the word system and its meaning later in the text as we do not need that now, but what we do need is to understand what it means in a practical sense. In everyday conversation we use the term loosely which helps to confuse understanding. In everyday speech we often refer to a ‘system’ when we mean a computer system. Many people, when told that one is involved in systems, assume that we mean that we are computer engineers. In other instances, people may use the term generally and speak of a system when referring to a government department. Such generalization is often the case when we complain about the unfairness of something: we blame the system. In recent times we hear newscasters and government spokespersons reporting a failure as being systemic, which seems to mean that no individual is to blame as the failure was a failure of the whole enterprise.

The way that we use the term system in everyday speech is imprecise and relies upon the listener interpreting what the speaker means. If there is plenty of agreement between the speaker and listener it suggests that the conversation is going well and that the speaker and listener inhabit the same area of interest (at least they assume that they do) but there is no guarantee that the system to which the speaker refers is the same one that the listener had in mind. The imprecise way that we use the word can be misleading, often resulting in the participants ending up with completely different understandings of the situation and worse, if we think of such a situation in terms of practitioner and client, what appears to be the right answer but is actually inappropriate to their particular problem.

A useful starting point in the practice of Systems thinking is to consider carefully what we mean when we refer to a system and define what system it is we are talking about. For example, if we were to discuss a transport system we need to decide what transport system it is we are considering. Is it freight? Is it a public transport system or is it a personal transport system that we mean (i.e. motor cars)? Do we include bicycles and other types of personal vehicle, and so on? Even when it seems we are referring to a computer system, do we mean just the hardware and software or are we including the people who are using it too? So let us agree some rules:

i. Always give the system a name.

ii. Agree that the name of the system to which the client is referring means the same thing to you!

Like many ideas in Systems, implementing such a simple idea is easier said than done but we have other ideas that can help us and the client to clarify what system it is we are interested in.

Some Simple Tools

Boundary and Environment

Most would agree that in any given circumstances it is wise to take into account as much of the situation as is possible before taking action. We need to see the situation in its entirety – that is to say to take in the whole, what we call adopting a holistic perspective. Many of us assume that we do this instinctively but often our horizons are limited by lack of experience of a new situation or awareness that things are changing from the familiar to something more challenging. When confronted with a new or a complex situation it is difficult to know where to start. The complexity of the situation itself can be overwhelming and it is not unusual at this stage that we can retreat to the safety of familiar techniques or rely on an individual within the situation to tell us what they think the problem is.

It is self evident that in any situation of interest we need to make decisions about what to include and what to leave out. Clearly a situation must have a beginning and an end point, and there must be some form of boundary around the system. If we do not do this then the alternative is that we will have to take the whole planet into account, which of course we cannot do; or conversely we slice up the problem into small pieces, but with this comes the danger that we might ignore important areas. One useful Systems idea is a simple yet powerful practical tool to help with this difficulty. The idea behind the ‘tool’ is the notion of boundary and environment.

What are these ideas and why are they useful? Many may be tempted to ask if they are just a fancy way of packaging up common sense. Well there is nothing common about common sense and the ideas which at first seem simple often have hidden depths which are realized as a user becomes more adept at using them. Despite the fact that, when confronted with a problem, most of us will consider the ‘system’ and make a mental note about what it seems to comprise, most do not represent it explicitly. We do not provide a clear enough description for the listener to understand and provide critical appraisal of what is being said. Using the idea of boundary we can begin, with those involved, to enrich understanding about the system – the situation of interest. But how do we set about deciding what is part of the system of interest and what is not? The first thing to remember is to beware a quick assessment. A hasty judgement can inhibit thinking, so take care. When you first draw your boundary remember that as you begin to understand what it contains, so will the boundary alter to reflect your richer understanding of the system of interest.

Let us consider an example. Imagine ‘A Manufacturing System’ is our area of interest. Where should we draw the boundary? We can start by thinking of things to exclude, including service industries and local government and obvious things like the entertainment industry and libraries. But what should we include? Well are we thinking of all aspects of manufacturing or specific areas such as those using metal? Do we wish to include all manufacturing or just those institutions within a given country? We need to decide what constitutes manufacturing. But, I hear you say, we would know the industry we were called upon to examine. This might be true but equally the practitioner might be asked to look into a changing manufacturing environment in which the company concerned needs to react.

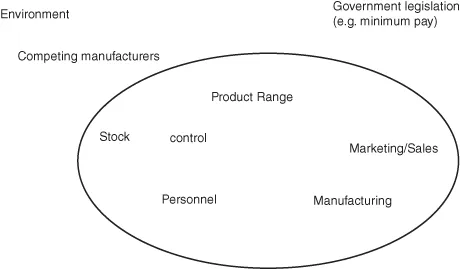

Initially, our boundary and environment might look like Figure 1.1 below:

Figure 1.1: Drawing a boundary

This diagram enables us to begin discussions with the members of the enterprise. As more is learned about the situation the boundary might add more sub-systems such as Production Control, Research and Development, Drawing Office and in its environment ‘Parent Company’ (which may control the policy that determines the market within which the enterprise can trade), Suppliers, Skills Availability and Sources of Capital. We may find as we begin to gain greater insight that one or more systems in our environment might be better placed within the boundary of the system itself or vice versa. For example, the parent company might have a Board member on the Board of the subsidiary, in which case a sub-system relating to that role should be within the boundary. It might be that the R&D department is part of the parent company and should be in the environment (it might be a separate cost centre that is contracted by various parts of the holding company’s portfolio).

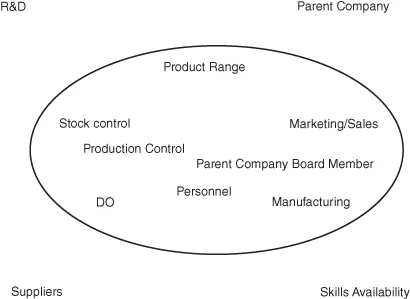

Following discussions with all concerned, the final diagram might now look like Figure 1.2:

Figure 1.2: Boundary and environment

Using what appears to be a simple diagram we can begin to gain an appreciation of the system itself and what is in its environment. The process of developing the diagram will play its part in enriching the understanding of those involved. The simple idea of drawing a boundary around the system of interest demands clarification about what the system is (it requires a name) and what component elements make it up. Once an agreement about the system has been reached the next stage is to decide what is in its environment and what is not. In this way we are beginning to be more precise in our description of the system of interest and its surroundings. The development of the diagram is a part of a process of learning for all those involved, the outcome of which is an agreed representation of the situation of interest and the context in which it exists.

We now move on to another apparently simple idea, that of a ‘black box’.

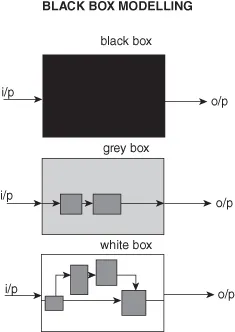

Black Box Diagrams

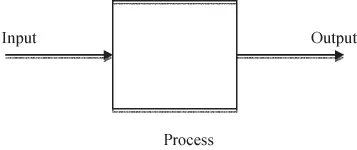

Another simple analytical tool that helps us make sense of complex issues is called a Black Box diagram. This thinking tool is borrowed from engineering where it is used to represent situations where the inner working of the product is less important than is the relationship between each of the sub-systems that make it up (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3: Black Box modelling

Black Box diagrams provide a useful means of representing a complex situation using the notion of ‘input → process → output’ which is common to many systems diagrams (see Figure 1.4):

Figure 1.4: Input–Process–Output diagram

The strength of a Black Box diagram is that there is no need to understand all the detailed processing that is undertaken inside the system as a whole, it is enough to recognize that ‘something’ happens and that this ‘something’ has particular inputs and outputs which can be identified. A further advantage of a Black Box diagram is that by obeying a few simple ‘rules’ the process can lead to a comprehensive learning exercise.

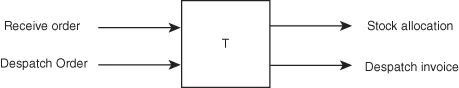

The first stage is to represent the whole system (i.e. the situation under investigation), as a single ‘input → process → output’ diagram. The system is named and the inputs to this system are listed and drawn and shown to be feeding into the system – let’s call it stock control. The outputs of this system are then identified and shown flowing out of the system as illustrated in Figure 1.5 below:

Figure 1.5: Simple first level Black Box diagram

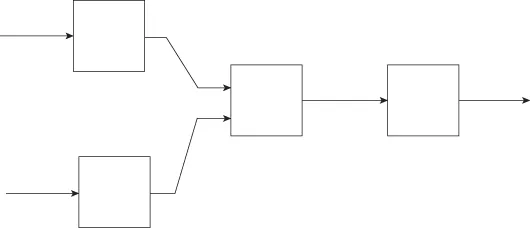

The given system is then ‘broken down’ into smaller wholes, or sub-systems, and the process of identifying the different inputs and outputs for each sub-system is undertaken until a list of all relevant sub-systems has been developed. The completed diagram may look as shown in Figure 1.6:

Figure 1.6: Outline of developed Black Box system

As is the case with most systems diagramming the idea is quickly learned but there are pitfalls as it is p...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- PART I: KEY SYSTEMS IDEAS

- PART II: SYSTEMS THINKING

- PART III: THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF PHILOSOPHY AND THE SOCIAL SCIENCES

- PART IV: CASE STUDIES

- Glossary

- References

- Index