- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Current Best Practice in Interventional Cardiology

About this book

Current Best Practice in Interventional Cardiology addresses the questions which challenge clinicians involved with interventional procedures. Helpfully organized into four sections, the text addresses; coronary artery disease, non-coronary interventions, left ventricular failure and the latest advances in imaging technologies, and provides authoritative guidance on the current recommendations for best practice.

Containing contributions from an international team of opinion leaders, this new book reviews the key advances in equipment, techniques and therapeutics and is an accessible reference forall hospital-based specialists.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Current Best Practice in Interventional Cardiology by Bernhard Meier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Cardiology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

CoronaryArteryDisease

CHAPTER 1

Acute Coronary Syndromes

Chapter Overview

- Acute coronary syndromes (ACS) are the acute manifestation of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease. Based on different presentations and management, patients are classified into non-ST-segment elevation ACS (NSTE-ACS) and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

- In western countries, NSTE-ACS is more frequent than STEMI.

- Even if the short-term prognosis (30 days) for NSTE-ACS is more favorable than for STEMI, the long-term prognosis is similar or even worse.

- Early invasive strategy is the management of choice in patients with NSTE-ACS, particularly in high-risk subgroups.

- Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the treatment of choice for STEMI. Facilitated PCI is of no additional benefit.

- The reduction of door-to-balloon time in primary PCI is critical for improved outcomes in STEMI patients.

- If fibrinolytic therapy is administered in STEMI, then patients should be routinely transferred for immediate coronary angiography, and if needed, percutaneous revascularization.

- High-risk ACS patients (eg, elderly patients, those in cardiogenic shock) have the greatest benefit from PCI.

- Antithrombotic therapy in ACS is getting more and more complex. The wide spectrum of antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants requires a careful weighing of ischemic and bleeding risks in each individual patient.

ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction

The term acute coronary syndrome (ACS) has emerged as useful tool to describe the clinical correlate of acute myocardial ischemia. ST-segment elevation (STE) ACS includes patients with typical and prolonged chest pain and persistent STE on the ECG. In this setting, patients will almost invariably develop a myocardial infarction (MI), categorized as ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The term non-ST-segment (NSTE) ACS refers to patients with signs or symptoms suggestive of myocardial ischemia in the absence of significant and persistent STE on ECG. According to whether the patient has at presentation, or will develop in the hours following admission, laboratory evidence of myocardial necrosis or not, the working diagnosis of NSTE-ACS will be further specified as NSTE-MI or unstable angina.

Recently, MI was redefined in a consensus document [1]. The 99th percentile of the upper reference limit (URL) of troponin was designated as the cut-off for the diagnosis. By arbitrary convention, a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)-related MI and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)-related MI were defined by an increase in cardiac enzymes more than three and five times the 99th percentile URL, respectively. The application of this definition will undoubtedly increase the number ofevents detected in the ACS and the revascularization setting. The impact on public health as well as at the clinical trial level of the new MI definition cannot be fully foreseen.

The extent of cellular compromise in STEMI is proportional to the size of the territory supplied by the affected vessel and to the ischemic length of time. Therefore a quick and sustained restoration of normal blood flow in the infarct-related artery is crucial to salvage myocardium and improve survival.

Primary PCI Versus Thrombolytic Therapy

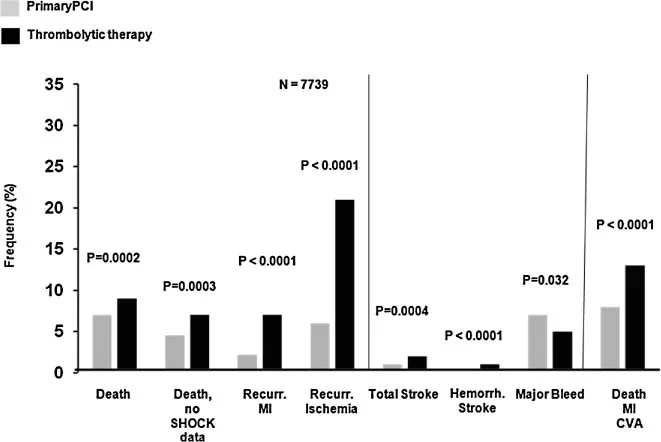

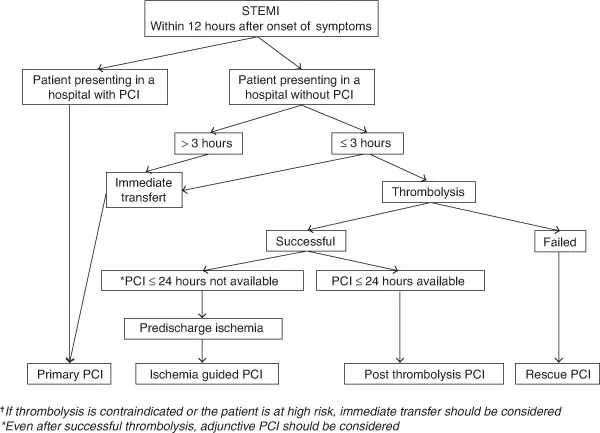

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention became increasingly popular in the early 1990s. Evidence favoring this strategy in comparison with thrombolytic therapy is substantiated by a metaanalysis of 23 randomized trials demonstrating that PCI more efficaciously reduced mortality, nonfatal reinfarction, and stroke (Fig. 1.1) [2]. The advantage of primary PCI over thrombolysis was independent of the type of thrombolytic agent used, and was also present for patients who were transferred from one institution to another for the performance of the procedure. Therefore, primary PCI is now considered the reperfusion therapy of choice by all the guidelines [3,4]. With respect to bleeding complications, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that the incidence of major bleeding complications was lower in patients treated with primary PCI than in those undergoing thrombolytic therapy [2]. In particular intracranial hemorrhage, the most feared bleeding complication, was encountered in up to 1% of patients treated with fibrinolytic therapy and in only 0.05% of primary PCI patients. The algorithm for treatment of patients admitted for a STEMI is presented in Fig. 1.2 [5].

Figure 1.1 Short-term clinical outcomes of patients in 23 randomized trials of primary PCI versus thrombolysis. (Reproduced with permission from [2] Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;361:13–20.)

Figure 1.2 Algorithm for revascularization in STEMI patients with less than 12 hours from symptom onset according to the 2005 ESC guideline for PCI. (Reproduced with permission [5] from Silber S, Albertsson P, Aviles FF, et al. Guidelines for percutaneous coronary interventions. The Task Force for Percutaneous Coronary Interventions of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:804–847.)

Advantages of Primary PCI

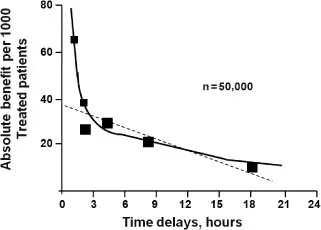

More than 90% of patients treated by primary PCI achieve normal flow (thrombosis in myocardial infarction [TIMI] grade flow 3) at the end of the intervention, while only 65% of patients treated by thrombolytic therapy benefit from this degree of reperfusion (Table 1.1) [6–8]. In addition, thrombolyis is characterized by a rapidly decreased efficacy after 2 hours of symptom onset (Fig. 1.3) [9]. There is a close relationship between the quality of coronary flow obtained after reperfu-sion therapy and mortality, and the prognosis of patients in whom flow normalization is not achieved is similar to that of patients with persistent vessel occlusion. The classification of TIMI myocar-dial blush grade allows an estimate of the tissue-level perfusion (Table 1.1). A critical link between lower TIMI myocardial blush grade, expression of a microcirculatory compromise, and mortality has been demonstrated in patients with normal epicardial flow following reperfusion therapy [10]. The improvement of clinical outcomes with primary PCI versus thrombolysis is also the consequence of a lower rate of reocclusion (0–6%). Accordingly, with thrombolytic therapy, reocclusion may occur in over 10% of cases even among patients presenting within the first 2 hours of symptom onset.

Mechanical complications of STEMI, such as acute mitral regurgitation and ventricular septal defect, were reduced by 86% by primary PCI compared with thrombolytic therapy in a meta-analysis of the GUSTO-1 and PAMI trials [11]. Free wall rupture was also significantly reduced by primary PCI [12]. Finally, primary PCI may allow earlier discharge (2–3 days following PCI versus 7 days following fibrinolytic therapy for uncomplicated courses).

Table 1.1 TIMI Classication of Coronary Flow and Perfusion

| Flow Grade Classification | |

| TIMI Flow Grade | Definition |

| 0 | No antegrade flow beyond the point of occlusion. |

| 1 | Faint antegrade coronary flow beyond the occlusion, although filling of the distal coronary bed is incomplete. |

| 2 | Delayed or sluggish antegrade flow with complete filling of the distal territory. |

| 3 | Normal flow that fills the distal coronary bed completely. |

| Perfusion Grade Classification | |

| Perfusion Grade | Definition |

| 0 | Minimal or no myocardial blush is seen. |

| 1 | Dye stains the myocardium; this stain persists on the next injection. |

| 2 | Dye enters the myocardium but washes out slowly so that the dye is strongly persistent at the end of the injection. |

| 3 | There is normal entrance and exit of the dye in the myocardium so that the dye is mildly persistent at the end of the injection. |

Adapted with permission from [7] Gibson CM, Schomig A. Coronary and myocardial angiography: angiographic assessment of both epicardial and myocardial perfusion. Circulation. 2004;109:3096–3105; and [8] Schömig A, Mehilli J, Antoniucci D, et al. Mechanical reperfusion in patients with acute myocardial infarction presenting more than 12 hours from symptom onset: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:2865–2872.

Figure 1.3 Time delays to thrombolysis in STEMI and the absolute reduction in 35-day mortality. (Reproduced with permission from [9] Boersma E, Maas AC, Deckers JW, Simoons ML. Early thrombolytic treatment in acute myocardial infarction: reappraisal of the golden hour. Lancet. 1996;348:771–775.)

Decreasing the Time to Reperfusion in Primary PCI

The survival benefit of reperfusion associated with thrombolytic therapy shrinks with increasing delay in the administration of the agent. For stable patients undergoing primary PCI, no association between symptom-onset-to-balloon time and mortality was observed in the U.S. NRMI registry [13]. In contrast, a significant increase in mortality was detected for patients with a door-to-balloon-time greater than 2 hours [14]. Therefore, the findings of primary PCI trials may be only applicable to hospitals with established primary PCI programs, experienced teams of operators, and a sufficient volume of interventions. Indeed, an analysis of the NRMI-2 registry demonstrated that hospitals with less than 12 primary PCIs per year have a higher rate of mortality than those with more than 33 primary PCIs per year [13]. Useful tools to decrease the door-to-balloon time are described in Table 1.2 [15].

Challenging Groups of Patients

Concomitant High-Grade Non-Culprit Lesions

The timing of revascularization of severe non-culprit lesion treatment in patients with multivessel

Table 1.2 Strategies to Reduce the Door-to-Balloon Time in Primary PCI

|

From [15] Bradley EH, Herrin J, Wang Y, et al. Strategies for reducing the door-to-balloon time in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2308–2320.

disease undergoing primary PCI has long been debated. Multivessel PCI in stable STEMI patients was found to be an independent predictor of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) at 1 year [16]. However, a recent study suggested that systematic revascularization of multivessel disease at the time of primary PCI in contrast to ischemia-driven revascularization may be of advantage because incomplete revascularization was found to be a strong and independent risk predictor for death and MACE [17]. Another study supported the notion that complete revascularization improved clinical outcomes in STEMI patients with multivessel disease [18]. Accordingly, the study showed a significant lower rate of recurrent ischemic events and acute heart failure during the indexed hospitalization. Nevertheless, current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines recommend that PCI of the non-infarct artery should be avoided in the acute setting in patients without hemodynamic instability [19].

Cardiogenic Shock

The incidence of cardiogenic shock in acute MI patients is in decline, accounting for approximately 6% of all cases [20]. As the result of the increasing use of primary PCI, the shock-related mortality has decreased. Accordingly, a U.S. analysis showed mortality rates in shock of 60% in 1995 and 48% in 2004, while the corresponding primary PCI rates were 27% to 54% [21]. In the SHOCK trial, early revascularization was associated with a significant survival advantage [22]. In the study, approximately two-thirds of patients in the invasive arm were revascularized by PCI and one-third by CABG surgery. Thrombolysis was administered in 63% of patients allocated to the medical stabilization arm. Early revascularization is strongly recommended for shock patients younger than 75 years. In older patients, revasc...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- Part I Coronary Artery Disease

- Part II Noncoronary Interventions

- Part III Treatment of Left Ventricular Failure

- Part IV Cardiovascular Imaging

- Index