![]()

Chapter 1

Methodology of Modeling in Biology and Ecology

1.1. Models and modeling

The notion of models in the field of biology emerged over the course of the 1960s and 1970s when it became apparent that more precision was required between the real-world subject of study and its representation through a mathematical object: the mathematical model. For living systems, one of the first major syntheses was created by J.-M. Legay [LEG 73]1. Since then, many groups and individuals have contributed to a more precise definition of this notion and, especially, the definition of a model construction and use strategy, i.e. a modeling approach. However, the development of this method has been a source of debate, with certain parties neglecting or denying its usefulness in biology and ecology, and other experts struggling with the idea that the mathematical and physical objects in question may appear simpler than the simplest virus or the most elementary macromolecule. Moreover, the difficulty of producing general laws written in a mathematical form is not always fully appreciated. This difficulty has two implications: firstly, it limits the applicable range of models, leading to a diversification of approaches, and secondly, it leads to a questioning of the approach itself. Finally, the difficulty in obtaining precise and sufficiently numerous measurements does not facilitate our task. This being said, we may no longer doubt the fact that modeling is recognized as an effective tool, particularly when integrated into a rigorous experimental approach.

Finally, while modeling is not necessarily a form of theorization, the construction of a model may prove to be a determining element; however, we must remember that a formula or mathematical object must, first and foremost, be operational, i.e. respond to the aims of the modeling activity, and, as far as possible, be interpretable in biological or ecological terms. This formula must be able to be translated into simple terms, accessible to all, to avoid esotericism in the language used: esotericism has a tendency to cover ignorance and leads to obscurantism.

1.1.1. Models

A model can be described as a symbolic representation of certain aspects of a real-world object or phenomenon, i.e. an expression or formula written following the rules of the symbolic system from which this representation stems. This may seem somewhat obscure. Firstly, we should illustrate the notion of a symbolic system. Let us take the example of natural integers. In everyday life, we use a set of ten symbols to represent the numbers 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9: the figures in the decimal system. The numbers we use to count, for example, the number of people in a room, are made up of a figure (from zero individuals, 0, to nine people, written as 9) or two or more figures in conjunction (for more than nine people). Moreover, we can perform defined operations using these numbers, for example addition, which allows us to use two numbers to obtain a third. These rules were not defined by chance, but correspond to a concrete reality. For example, if we know that a room contains 21 people and eleven more people enter the room, the addition 11 + 21 allows us to calculate the final number of people without needing to recount: 11 + 21 = 32. This demonstrates the operation of any symbolic system: we have a set of basic symbols which we can associate and transform using a set of rules specific to this system.

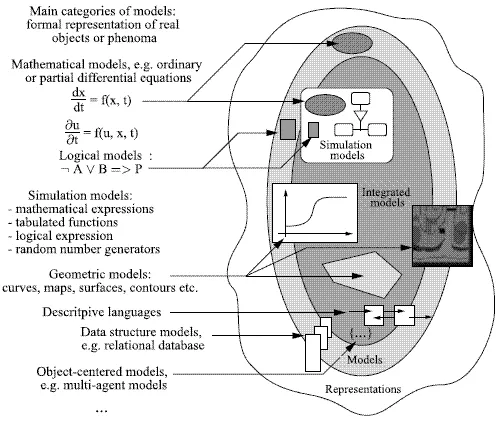

In practice, the symbolic systems used in modeling today are rather more complex, but are still based on the same principle. We encounter a wide variety of systems; in addition to everyday language, significant examples include:

– mathematical language, in which case we talk of mathematical models;

– computerized modes of representation (programming languages, database formalisms, knowledge-base formalisms, multi-agent formalisms, etc.;

– geometric representations: curves, surfaces, maps, etc.;

– and many others.

Figure 1.1. gives an idea of the most widespread symbolic representation systems. See the following for an example.

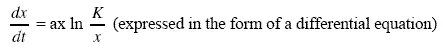

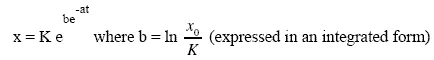

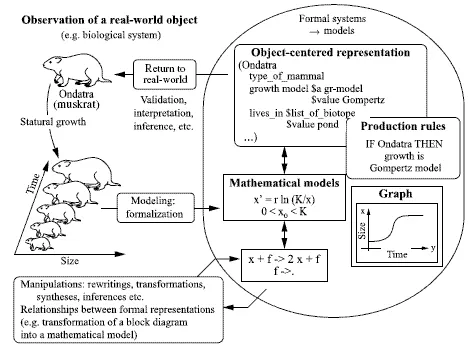

The Gompertz (mathematical) model

or

This model represents the growth of certain morphological variables, including height and body mass, in higher organisms (for example, the development of body mass in the muskrat presented in Chapter 3, section 3.5.2).

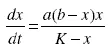

The Monod model

x represents the size of a population. This model provides a good representation of the growth of bacterial populations; we shall return to this example later.

Topographical maps and choremes

These provide users with a geometrical vision of the physical environment: for example, vegetation maps give a representation of vegetal coverage. Other symbolic systems may be used by geographers, for example, the choreme system proposed by Roger Brunet (see Brunet et al., [BRU 92], for example) to represent spatial organization and dynamics.

Functional representation

This diagram represents the growth of a biomass x in the presence of a growth factor f for which the dynamics are independent of the biomass. This diagram may be associated with the Gompertz model. It assists in the interpretation of the growth phenomena described by this model in functional terms.

One of the first problems we encounter is the choice of representation: we must represent well in order to solve well [MIN 88]. The integrated form of the Gompertz model, for example, is operational from a perspective of numerical calculation; the differential form, on the other hand, is better suited to interpretation. This expression is used to develop a block diagram, leading to the interpretation of the model in biological terms (see Chapter 2 and 3).

1.1.2. Modeling

Clearly, modeling is the approach which leads to the creation of a model. The process takes into account:

– the object and/or phenomenon being represented;

– the formal system selected;

– objectives, i.e. the use for which the model is intended;

– data (in relation to variables) and information (concerning the relationship between variables) already available or accessible through experimentation or observation.

The tasks which need to be accomplished clearly depend on the biological situation and formal system selected. However, in all cases, we must:

– carry out formalization activities in correspondence with the writing of the model;

– manipulate this model within the formal system to render it more “useable” (for example to obtain an integrated expression from a differential equation) and to study its properties;

– establish relationships with other representations (for example, the graph of a function, or the computer program which will allow users to calculate numerical values);

– interpret and compare the different representations obtained in the formal world with the biological reality (this reality is generally seen through experimental data).

1.2. Mathematical modeling

As we have seen, modeling may be based on formal systems other than mathematics. However, mathematical modeling is the best known, explored and developed system (having been in use for over 2000 years), both in terms of its internal operations and in terms of the relationships between mathematical objects and real objects or other representations (for example, geometric representations). The construction of mathematical representations follows the same type of schema laid out in Figure 1.2 (see Figure 1.3).

However, we should remember that most current knowledge in mathematics was obtained through problems in the domain of physics. The capacity of mathematics to solve certain problems in this discipline is astonishing: objects and concepts have emerged, the existence of which was suggested by the logic inherent in mathematics, permitting subtle physical interpretations. To take a current example, we might refer to gauge theory, or to the consequences of Lagrangian invariance for certain transformations known as symmetries. However, these extraordinary successes should not distract us from the fact that the picture is less rosy as soon as we move away from fundamental physics, even to the domain of “everyday” physics, particularly in terms of the physics of complex systems (for example, the correct treatment of the painter’s ladder problem, including friction and the “oscillations” produced by the painter climbing the ladder, which is no easy matter). Tackling biological systems is harder still. We do not know if “nature” is essentially mathematical2, but one thing we can say, without excessive positivism, is that mathematics developed essentially around certain physical problems, and while it is encouraging and astounding that it responds so well to these questions, this seems to be greater proof of the excellence of the human mind rather than of the presence of a profound mathematical “essence” in the world.

With our current knowledge, we are able to give a more detailed vision of modeling using a global diagram where the “elementary” steps are laid out (see Figure 1.4). Our discussion will be based on this diagram. In Figures 1.2 and 1.3 and, to a lesser extent, in Figure 1.4., we see that we refer ba...