- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Art and Science of HDR Imaging

About this book

Rendering High Dynamic Range (HDR) scenes on media with limited dynamic range began in the Renaissance whereby painters, then photographers, learned to use low-range spatial techniques to synthesize appearances, rather than to reproduce accurately the light from scenes. The Art and Science of HDR Imaging presents a unique scientific HDR approach derived from artists' understanding of painting, emphasizing spatial information in electronic imaging.

Human visual appearance and reproduction rendition of the HDR world requires spatial-image processing to overcome the veiling glare limits of optical imaging, in eyes and in cameras. Illustrated in full colour throughout, including examples of fine-art paintings, HDR photography, and multiple exposure scenes; this book uses techniques to study the HDR properties of entire scenes, and measures the range of light of scenes and the range that cameras capture. It describes how electronic image processing has been used to render HDR scenes since 1967, and examines the great variety of HDR algorithms used today. Showing how spatial processes can mimic vision, and render scenes as artists do, the book also:

- Gives the history of HDR from artists' spatial techniques to scientific image processing

- Measures and describes the limits of HDR scenes, HDR camera images, and the range of HDR appearances

- Offers a unique review of the entire family of Retinex image processing algorithms

- Describes the considerable overlap of HDR and Color Constancy: two sides of the same coin

- Explains the advantages of algorithms that replicate human vision in the processing of HDR scenes

- Provides extensive data to test algorithms and models of vision on an accompanying website

www.wiley.com/go/mccannhdr

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Art and Science of HDR Imaging by John J. McCann,Alessandro Rizzi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Electrical Engineering & Telecommunications. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Section F: HDR Image Processing

31

HDR Pixel and Spatial Algorithms

31.1 Topics

In Section F we will describe and analyze HDR algorithms that we have divided into a number of categories. We will emphasize the many variants of Retinex and ACE image processing and review analytical interpretations. We describe a number of different techniques to evaluate the success of different algorithms. Finally, we use what we have learned to discuss future research in HDR imaging.

31.2 Introduction – HDR Image Processing Algorithms

In Section A we described how the ideas of silver halide photography have influenced our thinking about images. We may never be sure if analyzing images one pixel at a time comes from Euclidean geometry, or the chemical mechanisms of silver halide photography, or the later influence of Thomas Young’s tricolor hypothesis. It may be a combination of all three. Regardless, there are many useful systems that perform successful predictions with calculations that limit the input information to that of a single pixel. Silver halide film models and colorimetry are good examples. We can calculate the response of a film from the quanta catch of the silver-halide grains at a small local region of the film. The film’s response to quanta catch is the same everywhere in the image. As well, we can predict whether two different spectra (wavelength vs. energy distributions) will match to humans. As we have seen many times in this text, calculations that are restricted to the information from a single pixel cannot predict human appearance, and are of limited value in HDR imaging.

Our analysis has the goal of evaluating an algorithm’s ability to render all types of scenes. If the process mimics the human visual system, then it must render appropriately LDR, HDR, low-average and high-average scenes using the same algorithm parameters. Using this as a performance standard is very helpful in evaluating the great variety of algorithms.

We will review image processing algorithms that use light (quanta catch) from:

one pixel,

a local group of pixels,

all the pixels,

and all the pixels in a way that mimics vision.

31.3 One Pixel – Tone Scale Curves

It is easy and efficient to apply tone scale curves to digital images. While color negative-to-print technology installed a fixed tone scale in the factory, digital photography can apply it using the individual’s personal computer. Although the practice is completely different, the principles are the same. Jones and colleagues sought the best compromise for optimal rendition of all types of scenes. They measured the limits of veiling glare, and designed negatives that in single exposures captured all the dynamic range possible after glare (Section B). There is no fundamental difference between film and digital tone-scale rendering. Both cannot address the issue raised by Land’s Black and White Mondrian, and “John at Yosemite” experiments. Nonuniform illumination, sun and shade, puts the same light on the camera’s film plane from white areas in the shade, and black areas in the sun. HDR scene rendition that mimics human vision requires spatial image processing.

There is a great irony in using Tone Scales to improve digital imaging. Tone scales were built into the chemistry of film processing. A great deal of practical image-quality research on the scenes people photographed determined the optimal tone scale response for prints and transparencies (Mees, 1961; Mees & James, 1966). Tone scales for film photography were optimal for pixel based image processing of all scenes. Pixel-based processing had to be the best compromise. It cannot respond differently to scene content. However, digital imaging has made spatial processing possible. Unlike film, that restricted spatial interactions to a few microns, electronic imaging has freed us from the fixed compromise of a global tone scale.

31.3.1 One Pixel – Histogram

A popular tool among digital photographers is histogram equalization. Histograms that plot the number of pixels for all camera quantization levels (e.g., 0 to 255) are very helpful in evaluating camera exposures. Over- and under-exposure is easily recognized in histogram plots. Engineers have developed programs that group quantization levels into bins, and then redistribute the bins with the goal of having a more uniform distribution of digital values. Histogram equalization programs process the image using the pixel-value population. It assumes that the image will look better if all the bins have an equal count. Histograms equalization programs completely ignore the spatial information in the input, and significantly distort the spatial relationships in the output. Many scenes are harmed by histogram-equalization renditions because they change the spatial relationships of image content.

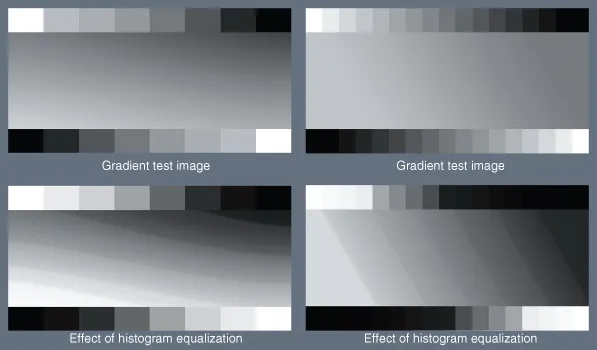

Figure 31.1 shows the effects of histogram equalization on a pair of test targets made up of gradients and uniform gray squares. The left and right targets have the same maximum, minimum and range. They have different gradients in the middle and more gray steps between max and min on the right. They differ in the image statistics; the number of pixels per digital value (0 to 255). In the gradients, pixels have very similar values to nearby pixels. Since histogram equalization just evaluates the statistics of the image, it does not preserve subtle local relationships. In the pair of test targets the gradient appears smooth and low in contrast. In the pair of histogram-equalized images below, the gradients are broken up into different bands of luminance, showing the algorithm’s indifference to local relationships. Furthermore, the gray scales at top and bottom have been rendered with lower contrast near white and black, but with higher contrast for mid-grays.

Figure 31.1 Banding created by histogram equalization. The top pair are different input images; the bottom pair are the outputs of the same histogram equalization algorithm.

Humans do not use image statistics in generating appearances. As we have seen in Sections D and E, the spatial relationships of the image content control appearances.

31.3.2 One Pixel – LookUp Tables

There is a great advantage to single-pixel processing. It is fast, low-cost, and requires minimal hardware. HDR algorithms frequently use LookUp Tables (LUTs) because they require only a small number of memory locations per color to load the digital values of the output. The operation is to read the memory value out at the appropriate address. This operation is simpler and faster than multiplying two numbers.

Single pixel techniques are ideal for manipulating the appearance of individual images which have a particular problem. There are many HDR guide books that can help to solve particular problems for particular scenes using multiple digital exposures, RAW format cameras and LUTs (Bloch, 2007; Freeman, 2008; McCollough, 2008; Correll, 2009; Fraser & Schewe, 2009). Although they often use the less powerful three 1-D LUT approach, they do great things to individual images.

Three-dimensional LUTs are an extremely powerful tool in making accurate reproductions and controlling color profiles (Pugsley, 1975; Kotera et al., 1978 Abdulwahab et al., 1989, McCann, 1995; 1997). Recall the analogy of color reproduction as the act of moving from an old house to a new one with different size rooms. The 3-D LUT process lets one use a different strategy in each room. It is much more powerful than three 1-D LUTs. Such 3-D LUTs play a major role in the color calibration processes of digital printers, displays and color management systems (Green, 2010).

31.3.3 Using 1-D LookUp Tables for Rendering HDR Scene Captures

Kate Devlin (2002) and Carlo Gatta (2006) wrote extensive reviews of the many tone scale LUTs and their underlying principles. Reinhard et al. (2006, Chapter 6) review the digital versions of conventional film tone-scale techniques. Although Reinhard provides many color illustrations of the processes, it is difficult to compare these approaches because each of the examples uses a different test image.

Applying the same pixel processing LUT (global operators) to any, and all, scene reproductions is not realistic. Some algorithms use a two step process to incorporate models of human vision. First, they assume that multiple-exposures can measure accurate scene luminance. Second, they apply a global-tone-scale map derived from psychometric functions, measured using isolated spots of light, rather than using scenes.

Many algorithms use some kind of psychophysical data to convert scene radiance to visual appearance. As well, psychophysical data are sometimes used outside of their original context. Similarities with human vision are taken as an inspiration, rather than modeling calibrated scene input with precise implementation of the experimental data. They have been inspired by Steven’s data on brightness perception (Tumblin & Rushmeier, 1993), Blackwell contrast sensitivity model (Ward, 1994), models of photopic and scotopic adaptation (Ferwerda, et al., 1996) differential nature of visual sensation (Larson et al., 1997), image statistics (Holm, 1996) adaptation and gaze (Scheel et al., 2000). Reinhard and Devlin (2004) used physiological data to modify uncalibrated cameras’ scene capture. They used Hood’s modification of Naka & Rushton’s famous equation describing an electrode’s extra-cellular post-receptor graded S-potential response of excised fish retinas.

There are many problems with such algorithms that prevent them from accurately predicting human vision. The captured scene data is an ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Wiley-IS&T Series in Imaging Science and Technology

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- About the Authors

- Preface

- Series Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Section A: History of HDR Imaging

- Section B: Measured Dynamic Ranges

- Section C: Separating Glare and Contrast

- Section D: Scene Content Controls Appearance

- Section E: Color HDR

- Section F: HDR Image Processing

- Glossary

- Author Index

- Subject Index