eBook - ePub

Development of Vaccines

From Discovery to Clinical Testing

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Development of Vaccines

From Discovery to Clinical Testing

About this book

Development of Vaccines: From Discovery to Clinical Testing outlines the critical steps, and analytical tools and techniques, needed to take a vaccine from discovery through a successful clinical trial. Contributions from leading experts in the critical areas of vaccine expression, purification, formulation, pre-clinical testing and regulatory submissions make this book an authoritative collection of issues, challenges and solutions for progressing a biologic drug formulation from its early stage of discovery into its final clinical testing. A section with details and real-life experiences of toxicology testing and regulatory filing for vaccines is also included.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Development of Vaccines by Manmohan Singh, Indresh K. Srivastava, Manmohan Singh,Indresh K. Srivastava in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Pharmacology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

IMMUNOGEN DESIGN

Chapter 1

Microbial vaccine design: the Reverse Vaccinology approach

1.1 Introduction

Infectious diseases are the greatest cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide; pathogenic bacteria are responsible for approximately 50% of this burden. From a public health standpoint, prevention of diseases has a greater impact and is more cost effective than treating the infection. Vaccines are the most cost-effective methods to control infectious diseases and at the same time one of the most complex products of the pharmaceutical industry. There are several infectious diseases for which traditional approaches for vaccine discovery have failed. With the advent of whole-genome sequencing and advances in bioinformatics, the vaccinology field has radically changed, providing the opportunity for developing novel and improved vaccines. Overall, the combination of different approaches (“-omics” approaches)—genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, structural genomics, proteomics, and immunomics—are being exploited to design new vaccines.

1.2 Historical View of “Classical” Vaccinology

The history of vaccination is traditionally dated to the publication, in 1798, of Edward Jenner's landmark experiments with cowpox in which he inoculated a neighbor's boy with purulent material from a milkmaid's hand lesion in the United Kingdom. The boy, 8 years old, was subsequently shown to be protected against a smallpox challenge. For more than 80 years, little more was done with respect to immunization, until Louis Pasteur discovered the attenuating effect of exposing pathogens to air or to chemicals. This discovery was achieved as the result of leaving cultures on the laboratory bench during a summer holiday. Thus, Pasteur developed the first vaccine made in the laboratory and also founded the terminology of vaccination (1, 2). Since the time of Pasteur until recently, there have been two paths of vaccine development: attenuation or inactivation and the production of recombinant subunits. With regard to attenuation, heat, oxygenation, chemical agents, or aging were the first methods used, notably by Pasteur for rabies and anthrax vaccines. Passage in an animal host, such as the embryonated hen's egg, was the next method, as practiced by Theiler for the yellow fever vaccine. After the development of in vitro cell culture in the 1940s, attenuation was accomplished by a variety of means, including selection of random mutants, adaptation to growth at low temperatures, chemical mutation to induce inability to grow at high temperature (temperature sensitivity), or induction of auxotrophy in bacteria. The second set of strategies are represented by the inactivation of the microorganism or by purifying small subunits derived from the pathogen of interest.

Late in the nineteenth century, Theobald Smith in the United States and Pasteur's colleagues independently showed that whole organisms could be killed without losing immunogenicity. This new strategy soon became the basis of vaccines for typhoid and cholera and later for pertussis, influenza, and hepatitis A. Other approaches consisted in isolation of virulence factors from the microorganisms, such as toxins or capsular polysaccharides. In the 1920s, the exotoxins of Corynebacterium diphtheriae and Clostridium tetani were inactivated by formalin, to provide antigens for immunization against diphtheria and tetanus (1). Extracted type-b polysaccharide capsule of Haemophilus influenzae was shown attractive as a vaccine antigen since the invasive disease was almost exclusively restricted to type-b organisms, and antipolysaccharide antibodies had an important role in natural immunity. However, early observations with Hib demonstrated the limitations of plain polysaccharide as a vaccine antigen. When given, during the first 2 years of life, purified polysaccharide induced relatively low levels of serum antibodies, typically insufficient to protect against invasive disease. Following further studies with a variety of bacterial polysaccharides, and in the light of the limitations of plain polysaccharide as vaccine antigens, the Hib polysaccharide was shown to be more immunogenic when covalently linked to a protein carrier, giving additionally boosted responses characteristic of T-dependent memory (3, 4). Overall, with the classical vaccinology approaches many infectious diseases can be prevented. Table 1.1 reports a list of vaccines licensed for immunization in the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (5).

Table 1.1 Vaccines Licensed for Immunization and in the United States approved by FDA

| Subunit Vaccines |

| Anthrax |

| Tetanus |

| Diphtheria |

| Pertussis |

| Haemophilus influezae |

| Hepatitis B |

| Human papillomavirus |

| Meningococcus (groups A, C, Y, and W-135) |

| Pneumococcal |

| Tetanus |

| Typhoida |

| Live Vaccines |

| Tuberculosis |

| Measles |

| Mumps |

| Rotavirus |

| Varicella |

| Yellow fever |

| Herpes zoster |

| Smallpox |

| Inactivated Vaccines |

| Hepatitis A |

| Influenzaa |

| Japanese encephalitis |

| Plague |

| Polio |

| Rabies |

a Additional live vaccine.

However, the above-metioned approaches have several limitations, including the fact that, in some cases, pathogenic microorganisms are difficult to culture in vitro and, therefore, production of live attenuated, inactivated, or subunit vaccines becomes impractical and time consuming. As a result, there are several infectious diseases for which these traditional approaches have failed and for which vaccines have not yet been developed.

1.3 Reverse Vaccinology

1.3.1 Classical Reverse Vaccinology: The MenB Story

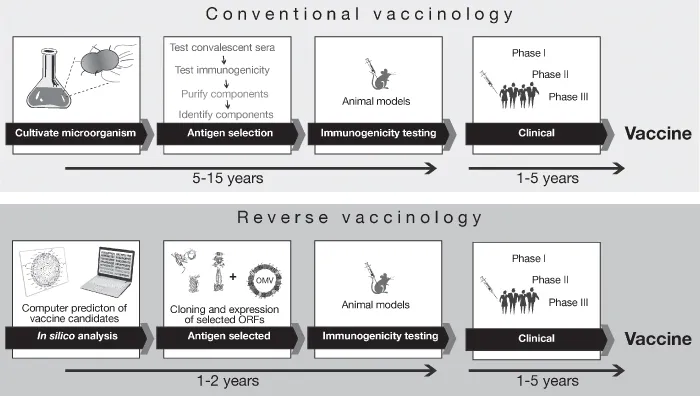

Conventional approaches to develop vaccines, as described above, are based on the cultivation of the microorganisms in vitro, and only abundant components can be isolated by using biochemical and microbiological methods. Although successful in many cases, these approaches have failed to provide vaccines against pathogens that did not have obvious immunodominant protective antigens (6). With the advent of whole-genome sequencing and advances in bioinformatics, the vaccinology field has radically changed, providing the opportunity for developing novel and improved vaccines. The availability of the complete genome sequence of a free-living organism (H. influenzae) in 1995 (7) marked the beginning of a “genomic era,” which allowed scientists to use new approaches for vaccine design and for the treatment of bacterial infections. With this powerful sequencing technology, a new approach to identify vaccine candidates was proposed on the basis of the genomic information. This approach was called reverse vaccinology (Fig. 1.1). The novelty of reverse vaccinology was not based on growing microorganisms but on running algorithms to mine DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) sequence information contained in the blueprint of the bacterium (8). The first step of this in silico analysis is the appropriate combination of algorithms and the critical evaluation of the coding capacity. The predicted open reading frames (ORFs) are used for homology searches against a database with BLASTX, BLASTN, and TBLASTX programs to identify DNA segments with potential coding regions. Since secreted or extracellular proteins are more accessible to antibodies than are intracellular proteins, they represent ideal vaccine candidates and therefore the surface localization criterion is applied. The in silico approach results in the identification of a large number of genes. It is, therefore, necessary to use simple procedures that allow a large number of target genes to be cloned and expressed. Once purified, the recombinant proteins are used to immunize mice. The postimmunization sera are analyzed to verify the computer-predicted surface localization of each polypeptide and their ability to elicit an immune response. The direct means to study the protective efficacy of candidate antigens is to test the immune sera in an animal model in which protection is dependent on the same effector mechanisms as in humans (9).

Figure 1.1 Schematic representation and time lines of classical vaccinology in comparison to the reverse vaccinology approach. (See insert for color representation of this figure.)

The reverse vaccinology approach has been applied for the first time to the bacterial pathogen Neisseria meningitides serogroup B. Although the use of vaccines based on the polysaccharide antigen has been successful for most of the species causing bacterial meningitis (H. influenzae type B, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and N. meningitidis serogroups A, C, Y, and W135), the same approach cannot be easily applied to meningococcus B. This is because the MenB polysaccharide is a polymer of α(2–8)-linked N-acetyl-neuraminic acid (or polisyalic acid), which is also present in glycoproteins of mammalian neural tissues. The poor immune response and the high risk of autoimmunity have hindered much of the research on the MenB polysaccharide (10). An alternative approach to the MenB vaccine was based on the surface-exposed proteins contained in outer membrane vesicles (OMVs). These vaccines have been shown both to elicit serum bactericidal antibody responses and to protect against developing meningococcal disease in clinical trials (11–13). Although these vaccines provided evidence of efficacy against the homologous strain, they show sequence and antigenic variability in their major components (14).

Thus, the genomic approach for target antigen identification was directed to develop a vaccine against serogroup B N. meningitides (15). Neisseria meningitidis is a Gram-negative diplococcus and an obligate human pathogen that colonizes asymptomatically the upper nasopharynx tract of about 5–15% of the human population. Five serogroups (A, B, C, W135, and Y) account for virtually all of the cases of meningococcal disease (16). N. meningitidis is the major cause of meningitis and sepsis, two devastating diseases that can kill children and young adults. Invasive meningococcal disease causes a significant public health burden worldwide, with approximately 500,000 cases and >50,000 deaths reported annually (6, 16). MenB represents the first example of the application of reverse vaccinology and the demonstration of the power of genomic approaches for novel antigen identification. In 2000, an invasive isolate of N. meningitides (MC58) was sequenced and analyzed to identify suitable vaccine candidates with the in silico approach decribed above. After discarding cytoplasmic proteins and known Neisseria antigens, 570 genes predicted to code for surface-exposed or membrane-associated proteins were identified. Successful cloning and expression was achieved for 350 proteins, which were then purified and tested for localization, immunogenicity, and protective efficacy. Of the 91 proteins found to be surface exposed, 28 were able to induce complement-mediated bactericidal antibody response, providing a strong indication of the proteins capability of inducing protective immunity (17). Additionally, in order to test the suitability of these antigens for conferring protection against heterologous strains, the proteins were evaluated for gene presence, phase variation, and sequence conservation in a panel of genetically diverse MenB strains representative of the global diversity of the natural N. meningitidis population (9). This analysis yielded a handful of antigens, which were both conserved in sequence and able to elicit a cross-bactericidal antibody response against all of the strains in the panel, demonstrating that they could confer general protection against the meningococcus. To strengthen the protective activity of the single-protein antigens and to increase strain coverage, the final vaccine formulation comprises a “cocktail” of the selected antigens. This vaccine is currently in phase III clinical trials (17, 18).

1.3.2 Reverse Vaccinology Applied to the Pan-Genome Concept

In the last decade, microbial genomic sequencing has experienced an exponential growth. Sequencing of 1129 bacterial genomes have been completed and 2893 are currently in progress (19). All of the genomic sequences are available in public databases, and they cover hundreds of species, as well as multiple pathogenic and commensal strains of the same species. Recently, an analysis of the Streptococcus agalactiae genome has led to the pan-genome definition for this pathogen (20). It was suggested that the genomic sequence of a single strain is not genetically representative of an entire species, due to the surprising intraspecies diversity. Subsequently, in order to develop a universal vaccine with a broad range of coverage against the major circulating strains, a combination of antigens representative of different strains of the same pathogen should be included. Therefore, the classical reverse vaccinology approach has now been extended to a wider number of genomes belonging to the same species, as performed for S. agalactiae.

S. agalactiae (commonly referred to as group B Streptococcus or GBS) is an encapsulated Gram-positive coccus. GBS strains are classified into 9 serotypes according to immunogenic characteristics of the capsular polysaccharides (Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, and VIII), and approximately 10% of serotypes are nontypeable (21). GBS was originally isolated in 1938 from animals (22), and is the main cause of bovine mastitis, an economically important problem in dairy cattle throughout the world (23). However, invasive group B streptococcal disease emerged in the 1970s as a leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality in the United States (24) and represents the most common etiological agent of invasive bacterial infections (pneumonia, septicemia, and meningitis) in human neonates (25, 26). The need for a vaccine against GBS is supported by the observation that the risk of neonatal infection is inversely proportional to the maternal antibody response specific for the GBS capsular polysaccharide. In fact, the transplacental transfer of maternal IgG antibodies protects infants from invasive group B streptococcal infection (27). As a first approach to vaccine development, capsular polysaccharide (CPS)–tetanus toxoid conjugates against all 9 GBS serotypes were shown to induce CPS-specific IgG that is functionally active in opsonization against GBS of the homologous serotype. Clinical phase 1 and phase 2 trials of conjugate vaccines prepared with CPS from GBS types Ia, Ib, II, III, and V revealed that these preparations are safe and immunogenic in healthy adults. Although these vaccines are likely to provide coverage against the majority of GBS serotypes that cause disease in the United States, they do not offer protection against pathogenic serotypes that are more prevalent in other parts of the world (e.g., serotypes VI and VIII, which predominate among GBS isolates from Japa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Contributors

- Part 1: Immunogen Design

- Part 2: Vaccine Platforms

- Part 3: Characterization of Immunogens

- Part 4: Formulation Optimization and Stability Evaluation

- Part 5: Clinical and Manufacturing Issues

- Index

- Color Plates