eBook - ePub

Homogeneous Catalysts

Activity - Stability - Deactivation

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Homogeneous Catalysts

Activity - Stability - Deactivation

About this book

This first book to illuminate this important aspect of chemical synthesis improves the lifetime of catalysts, thus reducing material and saving energy, costs and waste.

The international panel of expert authors describes the studies that have been conducted concerning the way homogeneous catalysts decompose, and the differences between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts.

The result is a ready reference for organic, catalytic, polymer and complex chemists, as well as those working in industry and with/on organometallics.

The international panel of expert authors describes the studies that have been conducted concerning the way homogeneous catalysts decompose, and the differences between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts.

The result is a ready reference for organic, catalytic, polymer and complex chemists, as well as those working in industry and with/on organometallics.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Elementary Steps

1.1 Introduction

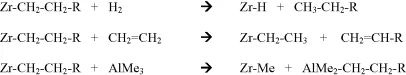

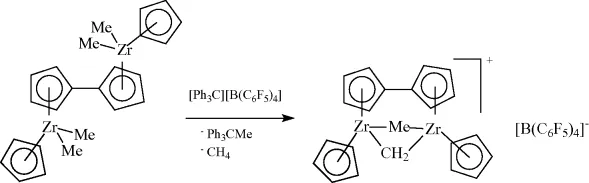

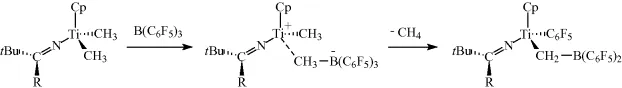

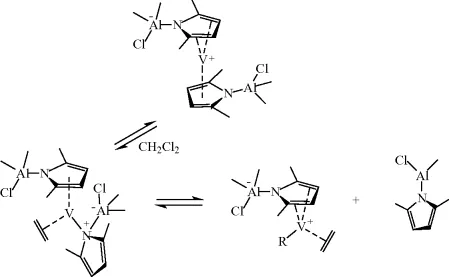

Catalyst performance plays a central role in the literature on catalysis and is expressed in terms of selectivity, activity and turnover number. Most often catalyst stability is not addressed directly by studying why catalysts perform poorly, but by varying conditions, ligands, additives, and metal, in order to find a better catalyst. One approach to finding a suitable catalyst concerns the screening of ligands, or libraries of ligands 1 using robotics; especially, supramolecular catalysis [2–4] allows the fast generation of many new catalyst systems. Another approach is to study the decomposition mechanism or the state the catalyst precursor is in and why it is not forming an active species. For several important reactions such studies have been conducted, but they are low in number. As stated in the preface, in homogeneous catalysis there has always been less attention given to catalyst stability [5] than there is in heterogeneous catalysis 6. We favor a combined approach of understanding and exploration, without claiming that this is more efficient. In the long term this approach may be the winner for a reaction that we have got to know in much detail. For reactions, catalysts, or substrates that are relatively novel a screening approach is much more efficient, as shown by many examples during the last decade; we are not able to study all catalysts in the detail required to arrive at a level at which our knowledge will allow us to make predictions. We can reduce the huge number of potential catalysts (ligands, metals, co-catalysts) for a desired reaction by taking into account what we know about the decomposition reactions of our coordination or organometallic complexes and their ligands. Free phosphines can be easily oxidized and phosphites can be hydrolyzed and thus these simple combinations of ligands and conditions can be excluded from our broad screening program. In addition we can make sophisticated guesses as to what else might happen in the reaction with catalysts that we are about to test and we can reduce our screening effort further. To obtain a better understanding we usually break down the catalytic reaction under study into elementary steps, which we often know in detail from (model) organometallic or organic chemistry. As many books do, we can collect elementary steps and reverse the process and try to design new catalytic cycles. We can do the same for decomposition processes and first look at their elementary steps [7]; the process may be a single step or more complex, and even autocatalytic. In this chapter we will summarize the elementary reactions leading to the decomposition of the metal complexes and the ligands, limiting ourselves to the catalysis that will be dealt with in the chapters that follow.

1.2 Metal Deposition

Formation of a metallic precipitate is the simplest and most common mechanism for decomposition of a homogeneous catalyst. This is not surprising, since reducing agents such as dihydrogen, metal alkyls, alkenes, and carbon monoxide are the reagents often used. A zerovalent metal may occur as one of the intermediates of the catalytic cycle, which might precipitate as metal unless stabilizing ligands are present. Precipitation of the metal may be preceded by ligand decomposition.

1.2.1 Ligand Loss

A typical example is the loss of carbon monoxide and dihydrogen from a cobalt hydrido carbonyl, the classic hydroformylation catalyst (Scheme 1.1).

Scheme 1.1 Precipitation of cobalt metal.

The resting state of the catalyst is either HCo(CO)4 or RC(O)Co(CO)4, and both must lose one molecule of CO before further reaction can take place. Thus, loss of CO is an intricate part of the catalytic cycle, which includes the danger of complete loss of the ligands giving precipitation of the cobalt metal. Addition of a phosphine ligand stabilizes the cobalt carbonyl species forming HCo(CO)3(PR3) and, consequently, higher temperatures and lower pressures are required for this catalyst in the hydroformylation reaction.

A well-known example of metal precipitation in the laboratory is the formation of “palladium black”, during cross coupling or carbonylation catalysis with the use of palladium complexes. Usually phosphorus-based ligands are used to stabilize palladium(0) and to prevent this reaction.

1.2.2 Loss of H+, Reductive Elimination of HX

The loss of protons from a cationic metal species, formally a reductive elimination, is a common way to form zerovalent metal species, which, in the absence of stabilizing ligands, will lead to metal deposition. Such reactions have been described for metals such as Ru, Ni, Pd, and Pt (Scheme 1.2). The reverse reaction is a common way to regenerate a metal hydride of the late transition metals and clearly the position of this equilibrium will depend on the acidity of the system.

Scheme 1.2 Reactions involving protons and metal hydrides.

Too strongly acidic media may also lead to decomposition of the active hydride species via formation of dihydrogen and a di-positively charged metal complex (reaction (2), Scheme 1.2). All these reactions are reversible and their course depends on the conditions.

As shown in the reaction schemes for certain alkene hydrogenation reactions and most alkene oligomerization reactions (Schemes 1.3 and 1.4), the metal maintains the divalent state throughout, and the reductive elimination is not an indissoluble part of the reaction sequence.

Scheme 1.3 Simplified scheme for heterolytic hydrogenation.

Scheme 1.4 Alkene oligomerization.

The species LnMH+ are stabilized by phosphine donor ligands, as in the Shell Higher Olefins Process (M=Ni) 8 and in palladium-catalyzed carbonylation reactions [9].

We mention two types of reactions for which the equilibrium, shown in Scheme 1.2, between MH+ and M + H+ is part of the reaction sequence, the addition of HX to a double bond and the Wacker reaction. As an example of an HX addition we will take hydrosilylation, as for HCN addition the major decomposition reaction is a different one, as we will see later. The hydrosilylation reaction is shown in Scheme 1.5 [10].

Scheme 1.5 Simplified mechanism for hydrosilylation.

In the Wacker reaction, elimination of HCl from “PdHCl” leads to formation of palladium zero [11] and the precipitation of palladium metal is often observed in the Wacker reaction or related reactions [12]. In the Wacker process palladium(II) oxidizes ethene to ethanal (Scheme 1.6) and, since the re-oxidation of palladium by molecular oxygen is too slow, copper(II) is used as the oxidizing agent. Phosphine ligands cannot be added as stabilizers for palladium zero, because they would be oxidized. In addition, phosphine ligands would make palladium less electrophilic, an important property of palladium in the Wacker reaction.

Scheme 1.6 Ethanal formation from ethene via a Wacker oxidation reaction.

In the palladium-catalyzed Heck reaction (Scheme 1.7), as in other cross coupling reactions, the palladium zero intermediate should undergo oxidative addition before precipitation of the metal can occur. Alternatively, Pd(0) can be “protected” by ligands present, as in the example of Scheme 1.7, but this requires another dissociation step before oxidative addition can occur. Both effective ligand-free systems [13] and ligand-containing systems have been reported [14]. A polar medium accelerates the oxidative addition. The second approach involves the use of bulky ligands, which give rise to low coordination numbers and hence electronic unsaturation and more reactive species. Turnover numbers of millions have been reported [15].

Scheme 1.7 The mechanism of the Heck reaction using excess phosphine.

1.2.3 Reductive Elimina...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Further reading

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- About the Author

- Chapter 1: Elementary Steps

- Chapter 2: Early Transition Metal Catalysts for Olefin Polymerization

- Chapter 3: Late Transition Metal Catalysts for Olefin Polymerization

- Chapter 4: Effects of Immobilization of Catalysts for Olefin Polymerization

- Chapter 5: Dormant Species in Transition Metal-Catalyzed Olefin Polymerization

- Chapter 6: Transition Metal Catalyzed Olefin Oligomerization

- Chapter 7: Asymmetric Hydrogenation

- Chapter 8: Carbonylation Reactions

- Chapter 9: Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions

- Chapter 10: Alkene Metathesis

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Homogeneous Catalysts by John C. Chadwick,Rob Duchateau,Zoraida Freixa,Piet W. N. M. van Leeuwen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences physiques & Chimie organique. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.