eBook - ePub

The World's Christians

Who they are, Where they are, and How they got there

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Written by an award-winning author, this well-organized and comprehensive introduction to global Christianity illuminates the many ways the world's Christians live their faith today.

- Covers the entire globe: Africa, Asia, and Latin America as well as Europe, North America, and the Pacific

- Provides impartial, in-depth descriptions of the world's four major Christian traditions: Orthodox, Catholic, Protestant, and Pentecostal/Charismatic

- Utilizes the best available sources to produce an up-to-date profile of demographic trends in the Christian population

- Blends history, sociology, anthropology, and theology to create a rich, multi-layered analysis of the world Christian movement

- Features clear maps and 4-color illustrations throughout the volume

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The World's Christians by Douglas Jacobsen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christianity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I Who They Are

Introduction

To be a Christian is to be a follower of Christ, but not all Christians follow Christ in the same way. That fact is underscored by a quick survey of the social structure of contemporary Christianity. Christians are institutionally divided into more than 35,000 separate churchly organizations, ranging in size from the enormous Roman Catholic Church which has more than a billion members to the grandly named Universal Church of Christ which has 400 members worldwide, most of them in the USA and the West Indies. Every week, Christians gather at more than five million local churches and parishes to worship God. And that’s just the formal structure. Informally, there are millions of additional Christian groups which meet in homes, schools, and places of work for Bible study, prayer, and mutual support. Each of these groups and each individual follower of Christ is in some sense unique, yet almost all of the world’s two billion Christians are affiliated with one or another of four major Christian traditions that dominate the movement today: Eastern Orthodoxy, Roman Catholicism, Protestantism, and the Pentecostal/Charismatic movement.

The word "tradition" comes from the Latin world traditio, which means “to hand down,” and religious traditions represent specific packages of beliefs, practices, and spiritual attitudes and emotions that have been handed down within different religious communities from generation to generation for years, if not centuries. This definition of tradition might make it sound as if religious traditions never change, but that is not the case. All traditions change, though most change slowly. In essence, a religious tradition is like a long, multigenerational conversation in which each new generation adds its own new insights and concerns, sometimes affirming and sometimes critiquing and revising what was done in the past. Over the course of two millennia, Christianity has produced a number of different major traditions, each with its own distinct sets of beliefs, practices, and spiritual affections. Some historical Christian traditions have become extinct, but the four traditions described in Part I are still quite vigorous and strong.

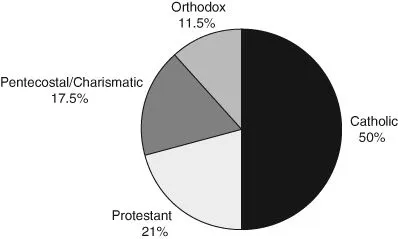

Figure I.1 The four major contemporary Christian traditions (% of total global Christian population)

Within the overarching category of being Christian, most individuals see themselves as belonging to one and only one of these four traditions. A person is either a Catholic or a Protestant or an Orthodox or a Pentecostal/Charismatic Christian. But while this general rule of thumb rings true for most Christians, there is sometimes fuzziness at some of the boundaries. Thus, for example, some people think of themselves as Orthodox Catholics (because they are members of Catholic Churches that use an Orthodox liturgy for worship) and others consider themselves to be both Catholic and Protestant, most notably “Anglo-Catholic” members of the Church of England. This kind of blurring of identity is especially common at the borders where the Pentecostal/Charismatic tradition touches the Protestant and Catholic traditions, with literally millions of Christians considering themselves both Catholic and Charismatic or both Protestant and Pentecostal. Even with these exceptions, however, most of the world’s Christians can be classified quite easily into just one of the four major traditions.

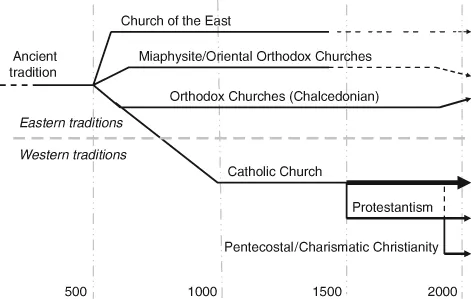

The Catholic tradition has the largest number of adherents, including roughly half of all the Christians in the world. The Protestant tradition comes next in terms of size, followed closely by the Pentecostal/Charismatic movement. Eastern Orthodoxy is the smallest of the four major traditions. (See Figure I.1.) A full accounting of the world’s Christians would also need to acknowledge a handful of other traditions that cannot be shoehorned into the big four. Some of these were once large and important Christian traditions such as the Church of the East (sometimes called the Nestorian Church) and the Miaphysite Churches (also known as the Oriental Orthodox Churches); see Figure I.2. Others are much smaller or of much more recent origin, such as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (also known as the Mormon Church). These smaller alternative traditions will be discussed where appropriate in the regional and historical sections of this book, but they are not given separate treatment here.

Every Christian tradition has a beginning point, though the particular “birth date” of a tradition is not always easy to identify. The Pentecostal/Charismatic movement is the youngest of the four major traditions, and its beginning is the easiest to date, usually being associated with the Azusa Street Revival, which took place in Los Angeles, California from 1906 to 1908 under the leadership of the African American preacher William J. Seymour. October 31, 1517 is sometimes cited as the start-up date for the Protestant movement – the day when Martin Luther first posted his famous “95 Theses” protesting the practices of the Roman Catholic Church on the door of the church in Wittenburg, Germany where he served as both priest and university professor. The origins of the Catholic and Orthodox traditions are harder to date, both because these traditions are ancient and because each emerged slowly as the result of a long process of development and consolidation. Many of the ingredients that make up these two traditions existed from the earliest years of the Christian movement, but those ingredients had to be mixed and baked for quite some time before they took on the specific characteristics that still define these traditions as they exist today. Viewed in terms of their contemporary identities, the Orthodox tradition can be said to have acquired its distinctively Orthodox shape around the ninth century, while the Catholic tradition developed its decisively Catholic identity sometime around the twelfth century.

Figure I.2 Development of major historical Christian traditions

The Orthodox Tradition

Today there are about 240 million Orthodox Christians in the world, accounting for roughly 12 percent of the world’s total Christian population. They are part of a family of about 40 independent and geographically defined churches that all see themselves as part of a single Orthodox tradition. The Orthodox tradition is defined by its shared consensus rather than by a hierarchically imposed uniformity. Historically, the highest office within the Orthodox tradition is the Patriarch of Constantinople (also known as the “Ecumenical Patriarch”), but this title denotes honor and respect, not power or control. Most contemporary Orthodox Churches are organized along national lines, a fact that is reflected in names such as the Greek Orthodox Church or the Romanian Orthodox Church or the Russian Orthodox Church (which is the largest of the Orthodox Churches, having about 115 million members). For Orthodoxy, the liturgy (the service of worship in the church building) is at the center of lived faith, and Orthodox worship is a full body experience that involves hearing the words of the prayers, seeing the images (icons) of the saints that are painted on the walls and ceiling, and smelling the incense that wafts through the room from the censors swung back and forth by the priests.

The Catholic Tradition

The Catholic tradition is housed almost entirely within the single massive institution that is known as the Roman Catholic Church. This church is overseen by the Bishop of Rome, who is also called the “Pope” (meaning “papa” or “father”). The current Pope is Benedict XVI, who assumed office in 2005 after the death of his long-serving and popular predecessor, John Paul II. Because of its size and its hierarchical organizational structure, the Catholic Church can appear to be a monolith when viewed from the outside. But the term “catholic” means literally “from the whole,” and the Catholic Church has always been a big tent where many different expressions of Christian faith and practice have been able to exist side by side within the wholeness of the church as a corporate body. The Catholic Church is the most ethnically and culturally diverse organization in the world, with more than 130 nations having at least 100,000 Catholics living within their borders. The five nations with the largest Catholic populations are Brazil (145 million), Mexico (90 million), the United States (70 million), the Philippines (65 million), and Italy (55 million).

Protestantism

The Protestant tradition is housed in a bewildering mix of thousands of different separate, independent denominations. Catholic and Orthodox Christians often consider the Protestant tradition to be unruly. In fact it is – but that is also the point. Protestants view faith largely as an individual matter, and Protestants are encouraged to read the Bible and determine what it means for themselves. As diverse and confusing as Protestantism can sometimes seem, the overall pattern is actually tidier than one might suppose. While Protestantism has tended to fragment with time, like-minded Protestants have also been busy gathering themselves together into a relatively limited number of major Protestant subtraditions. The largest of these are the Anglican, Baptist, Lutheran, Methodist, and Reformed subtraditions, and these five groups together account for roughly 85 percent of the almost 400 million Protestants in the world today.

The Pentecostal/Charismatic Movement

The newest of the four major contemporary Christian traditions is still in the early stages of formation. It has one core tenet: God is still active in the world through the Holy Spirit, so that miracles and spiritual gifts are an expected component of the Christian life. But while the movement’s distinctive emphasis is relatively easy to describe, the boundaries of the movement are somewhat fuzzy, and they are fuzzy precisely because Pentecostal/Charismatic faith is defined by an emphasis rather than by a distinctively different set of beliefs. The question is how much emphasis a particular group has to place on the active work of the Holy Spirit in order to qualify as Pentecostal/Charismatic. Answers to that question differ considerably and, as a result, claims about the size of the worldwide Pentecostal/Charismatic movement vary widely. On the low side, some say that the movement now accounts for roughly 10 percent of the world’s Christians. On the high side, some say 25 to 30 percent of the world’s Christians are now Pentecostal/Charismatic in orientation. The 17.5 percent figure used in this book represents a middling estimate based on a careful region-by-region analysis of the numbers.

In the next four chapters these traditions are examined in more detail, with each chapter following the same basic format. First, the spirituality (the core convictions and lived experience) of believers in each tradition is described. Each chapter then explores how the Christian concept of salvation is understood. A third section focuses on the structure of the tradition, the movement’s institutional and sociological organization. Finally, there is a brief outline of the story (or history) of the tradition. Taken together, these chapters provide a broad-brush description of contemporary Christianity. They answer the question “Who are the world’s Christians?” by explaining how different Christians conceptualize God and salvation, how they have organized their churches, how they have institutionally housed and preserved their particular form of Christian faith, and how they have passed that faith down from generation to generation.

Chapter 1

The Orthodox Tradition

Orthodoxy has the longest history of the four major Christian traditions that exist today, and it preserves the ancient ideas and practices of Christianity more fully than any other tradition. In many ways, the past is still alive in Orthodoxy, so much so that some outsiders view Orthodoxy as locked in the past. But for its adherents, Orthodox Christianity is very much a living faith, connecting them to the present and future as much as to the past.

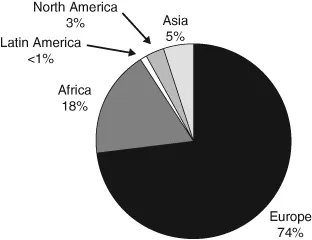

Geographically, the original heartland of Orthodoxy was the Middle East and the southern Balkans (the area that is now Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, and Macedonia). By 1500, however, under increasing pressure from Islam, the geographic center of Orthodoxy had moved north into Russia and Eastern Europe, where Orthodoxy remains the majority religion today. Three-quarters of all the Orthodox Christians in the world now live in Europe. In the twentieth century, Orthodoxy suffered greatly as most of Eastern Europe fell under Communist rule, but it endured and is currently enjoying a revival throughout the post-Communist world.

While Orthodoxy is the most geographically limited of the four major Christian traditions (see Figure 1.1), it too has become a global faith, with the Orthodox diaspora – the many communities of Orthodox Christians that now live outside of the Middle East and Eastern Europe – thinly circling the world. After Europe, Africa has the next largest number of Orthodox Christians, though most of the African Orthodox population (more than 90 percent) lives in just two countries: Egypt and Ethiopia. The Orthodox presence in Asia and Latin America (especially Brazil and Argentina) is generally small and spotty, but it exists. While the Orthodox population in North America and Australia is also relatively small, it is generally more robust. In North America, in particular, a significant experiment in Orthodox history is taking place. The Orthodox community in that region is highly complex – people from many different Orthodox Churches have moved to the area – and Orthodox leaders are currently trying to figure out how to unify all those Orthodox believers into a single “pan-Orthodox” movement. That process is prompting considerable theological reflection and creativity in some circles (those favoring the Americanization of the tradition) and significant anguish in others (those wanting to hold on to the often deeply intertwined religious and ethnic identities of the past).

Figure 1.1 Where Orthodox Christians live (% of global Orthodox population living in each continent)

Spirituality

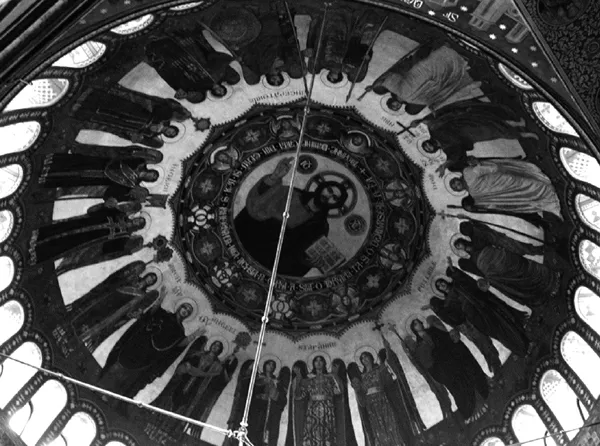

The spirituality of Orthodoxy focuses on worship, and to enter an Orthodox church is to enter a different place and time. Orthodox Christians view the liturgy (worship services held in the church building) as a way of participating briefly in the eternal worship of God that is always taking place in heaven. Most Orthodox churches have domed ceilings, and at the top of the dome there is an opening called the oculus. This is a symbolic eye into heaven and it is often encircled with windows. A huge icon (holy painting) of Christ as Pantokrator (the ruler of all) is painted in the oculus (see Figure 1.2), and Christ with the angels and apostles around him looks down on the gathered congregation where traditionally everyone stands, rather than sits, as a way of showing respect to God and to all the citizens of heaven.

Within an Orthodox church, one is surrounded by icons: icons on the ceiling, on the walls, on the screen or partition at the front of the church which is called an iconostasis, and on stands scattered throughout the building (see Figure 1.3). Icons portray not only Christ, but also Mary, the angels, and the great saints of the past. Other icons depict the stories of the Bible or important events in the history of Christianity. This panorama of images is intended to make those inside the building feel as if they are enveloped within a great community of faith, extending back in time thousands of years and looking forward together toward the future when God will welcome all the faithful into heaven. On the Orthodox way toward God no one walks alone. Rather, the journey toward God takes place in the constant company and with the ongoing assistance of others. That company includes both the living and the dead. In Orthodoxy, the boundary between the living and the dead is thin, and the Orthodox believe that the saints – holy men and women who have died – can still hear their cries for help and assist them in times of need.

In the same way that the line between life and death is thinned in Orthodoxy, the line between the sacred and the secular is also visually blurred in Orthodox iconography. The sacred and the secular interpenetrate, overlapping in time and space. Thus angels are everywhere in the icons because the Orthodox think they are everywhere in reality. The Orthodox believe that at the time of baptism every Christian is assigned a guardian angel for protection from evil and for guidance in the way of holiness and truth, but fallen angels (demons) are also ubiquitously present, seeking to turn people away from God and the path of faith. Because this spiritual world is hidden from view, humans tend to forget it. The liturgy and the icons remind people that they live within an invisible spiritual world of angels and demons just as literally as they live in the visible realm of the material world. In fact, the brilliance of the colors used in the painting of icons – and most of them were originally quite brilliant even though many old icons have grown dark with age – are luminous reminders that the spiritual world is as real, or more real, than the earth itself.

Figure 1.2 Holy Trinity Orthodox Cathedral (Sibiu, Romania), interior of main dome. Photo by author.

All of this communicates that nothing is ever done in secret. Life is lived in community. God is watching; Jesus is watching; Mary is watching; the angels are watching. And the saints are watching too. In fact, Orthodox icons – which are often displayed in homes as well as in churches – are understood to be not merely spiritual representations, but are also ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part I Who They Are

- Part II Where They Are

- Part III How They Got There

- Plates

- Index