![]()

1

The basics of cancer

If the three worst words are, ‘You have cancer’, then the four worst are ‘Your cancer is back’.

Katie Couric, American newscaster and journalist

CHAPTER CONTENTS

- Cancer is a complex entity

- Cancer through the ages

- Modern day cancer research and treatment

- Prevalence and mortality varies with each cancer

- Risk factors have been identified

- Will cancer be conquered within our lifetime?

- Expand your knowledge

- Additional readings

Very little strikes more fear into peoples’ hearts than being told they have cancer. Such a diagnosis can turn a person’s world upside down and conjure up thoughts of what lies ahead: pain, disfigurement, disability, nausea, hair loss, or even death. Recent years, however, have seen extraordinary advances in basic cancer research and in the development of more effective methods for the detection, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer. Consequently, while the phrase “You have cancer,” may be life-altering, it is not necessarily the devastating, life-threatening diagnosis of generations past.

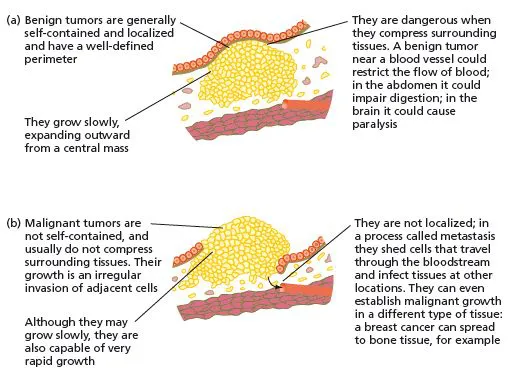

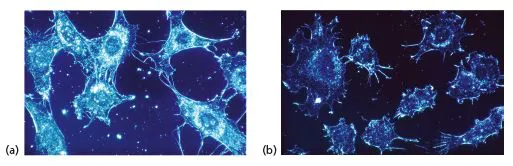

CANCER IS A COMPLEX ENTITY

In the most basic sense, cancer is the abnormal, uncontrolled growth of previously normal cells. The transformation of a cell results from alterations to its DNA that accumulate over time. The change in the genetic information causes a cell to no longer carry out its functions properly. A primary characteristic of cancer cells is their ability to rapidly divide, and the resulting accumulation of cancer cells is termed a tumor. As the tumor grows and if it does not invade the surrounding tissues, it is referred to as being benign (Figure 1.1a). If, however, the tumor has spread to nearby or distant tissues then it is classified as malignant (Figure 1.1b). Metastasis is the breaking free of cancer cells from the original primary tumor and their migration to either local or distant locations in the body where they will divide and form secondary tumors.

Do benign or malignant cells form metastatic tumors?

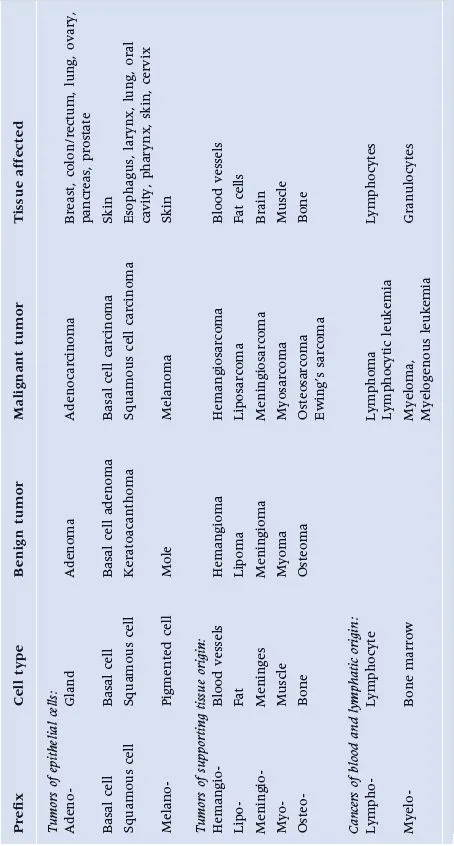

There are many types of cancer

Cancer is not a single disease; there are over 100 identified types, all with different causes and symptoms. To distinguish one form from another the cancers are named according to the part of the body in which they originate. Some tumors are identified to reflect the type of tissues they arise from, with the suffix -oma, meaning tumor, added on. For example, myelos- is a Greek term for marrow. Thus, myeloma is a tumor of the bone marrow, whereas hepatoma is liver cancer (hepato- = liver), and melanoma is a cancer of melanocytes, cells found primarily in the skin that produce the pigment melanin. (Table 1.1)

There are four predominant types of cancer

The four major types of cancer are carcinomas, sarcomas, leukemias, and lymphomas. Approximately 90% of human cancers are carcinomas, which arise in the skin or epithelium (outer lining of cells) of the internal organs, glands, and body cavities. Tissues that commonly give rise to carcinomas are breast, colorectal, lung, prostate, and skin. Sarcomas are less common than carcinomas and involve the transformation of cells in connective tissue such as cartilage, bone, muscle, or fat. There are a variety of sarcoma subtypes and they can develop in any part of the body, but most often arise in the arms or legs. Liposarcoma is a malignant tumor of fat tissue (lipo- = fat) whereas a sarcoma that originates in the bone is called osteosarcoma (osteo- = bone).

What is the difference between the terms hepatoma and hepatocarcinoma?

Certain forms of cancer do not form solid tumors. For example, leukemias are cancers of the bone marrow, which leads to the overproduction and early release of immature leukocytes (white blood cells). Lymphomas are cancers of the lymphatic system. This system, which is a component of the body’s immune defense, consisting of lymph, lymph vessels, and lymph nodes, serves as a filtering system for the blood and tissues.

Each cancer is unique

While there are certain commonalities shared by cancers of a particular type, each may be unique to a single individual. This is because of different cellular mutations that are possible, and can depend on whether the disease is detected at an early or advanced stage. As a result, two women diagnosed with breast cancer may or may not receive the same treatment. The impact of the disease on the individual, as well as the final outcome of the disease, is unique in every case. Still, several types of cancers can have a similar set of symptoms, which may be shared with several other conditions, making screening, detection, and diagnosis a complex problem.

A tumor can impact the function of the tissue in which it resides or those in the surrounding areas. Tumors provide no useful function themselves and may be considered “parasites,” with every step of their advance being at the expense of healthy tissue (Figure 1.2). While most types of cancers form tumors, many do not form discrete masses. As previously stated, leukemia is a cancer of the blood that does not produce a tumor, but rather rapidly produces abnormal blood cells in the bone marrow at the expense of normal blood cells.

The development of tumors

All tumors begin with mutations (changes) that accumulate in the DNA (genetic information) of a single cell causing it and its offspring to function abnormally. DNA alterations can be sporadic or inherited. Sporadic mutations occur spontaneously during the lifespan of a cell for a number of reasons: a consequence of a mistake made when a cell copies its DNA prior to dividing, the incorrect repair of a damaged DNA molecule, or chemical modification of the DNA, each of which interferes with expression of the genetic information. Inherited mutations are present in the DNA contributed by the sperm and/or egg at the moment of conception. To date, 90–95% of diagnosed cancers appear to be sporadic in nature and thus have no heredity basis. Whether the mutations that result in a cancer are sporadic or inherited, certain genes are altered that negatively affect the function of the cells.

Genetic influence on tumors

A link between a particular genetic mutation and one or more types of cancers is made by analyzing and comparing the DNA of malignant tissue samples obtained from patients and members of families with a high incidence of a particular cancer and comparing it to the DNA from healthy individuals. For example, a study could be conducted in which the DNA isolated from tumor cells obtained from liver cancer patients is analyzed and determined to possess certain versions of genes whereas different versions of those same genes are present in the DNA of liver cells of healthy persons. An association could then be drawn between the “bad” versions of those genes and liver cancer.

This type of analysis has been crucial in identifying certain versions of genes associated with a predisposition for the development of particular forms of cancer. For example, studies have demonstrated that there is an elevated risk of breast or ovarian cancer associated with certain versions of the BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 genes (Chapter 8). Another example is retinoblastoma, a rare tumor of the eye typically found in infants and young children, which is associated with alterations within the Rb gene (Chapter 4).

CANCER THROUGH THE AGES

Although not specifically identified as such, cancer has been known for many centuries. In fact, there is evidence of tumors in the bones of five thousand year old mummies from Egypt and Peru. The disease itself was not very common, nor explored or understood, because in ancient times fatal infectious diseases resulted in shorter lifespans. Given that the vast majority of cancers are sporadic, there was less opportunity for the accumulation of the mutations necessary to transform normal cells into cancerous ones.

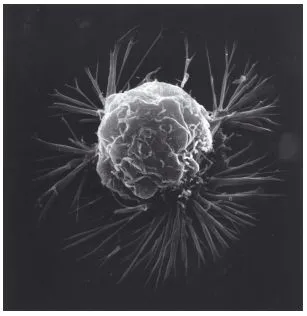

The word “cancer” was first introduced by Hippocrates (460–370 BC), the Greek physician and “father of medicine” (Figure 1.3). He coined the term carcinoma, from the Greek word karcinos, meaning “crab,” when describing tumors. This is because tumors often have a central cell mass with extensions radiating outward that mimic the shape of the shellfish (Figure 1.4).

Hippocrates believed that the body contained four “humors” or body fluids, and that each fluid was associated with a specific personality or temperament characteristic. “Blood” persons had a sanguine or optimistic personality with a passionate, joyous disposition. Someone with a dull or sluggish temperament would have “Phlegm.” Possessing “Yellow Bile” meant that one was quick to anger, while having “Black Bile” indicated a person was melancholic or depressed. In medieval times, it was believed that disease was a result of an imbalance of any of the four humors and physicians could restore health or harmony by purging, starving, vomiting, or bloodletting. In particular, an excess of black bile was thought to be the primary cause of cancer. This theory was accepted and taught for over 1300 years through the Middle Ages and championed by Claudius Galen (131–201 AD), a Greek physician and writer who described many diseases using this hypothesis (Figure 1.5). Both Hippocrates and Galen defined disease as a natural process, a theory that remained for centuries.

Box 1.1

Bloodletting as a medical practice

Interestingly, bloodletting is a method used in modern medical practice. The FDA formally approved the use of leeches as medical devices in June 2004. The invertebrate bloodsuckers are most often used following reconstructive surgery for the reattachment of fingers and toes to remove the excess blood that accumulates from severely damaged blood vessels. Since pooled blood often inhibits the healing of wounded tissues, the leeches’ ability to extract it is beneficial and efficient. Hirudin is an effective anti-blood clotting agent present in the saliva of the leech that keeps the blood flowing, giving time for the vessels and tissues to heal. Although it seems as if leech therapy would be painful, it is not thanks to a mild anesthetic the leeches produce.

The use of autopsies is very significant to medical discoveries

Unfortunately, during the Middle Ages the dissection of cadavers was largely prohibited for religious reasons, or yielded little data when conducted at all, due to its primitive nature. The failure to recognize the benefits of studying cadavers, or the understandable ignorance of the times, arguably delayed the progress of medical science. As a result, one of medicine’s most informative research tools, dissection of cadavers, was largely ignored.

The English physician William Harvey (1578–1657) is credited with conducting the first examples of postmortem (after death) analysis (Figure 1.6). Although rare and certainly unscientific by modern standards, his “public dissections” are now known as autopsies. Giovanni Morgagni (1682–1771), an Italian physician, is considered the founder of pathological anatomy (Figure 1.7). In 1761, at the age of 79, he published a book describing nearly 700 autopsies that he had performed associating a patient’s cause of death to the pathological findings made postmortem. His work was a far cry from the theory of “humors” that had previously existed and laid the foundation for the serious study of cancer as a cause of morbidity (disease) and mortality (death).

Early discovery of carcinogens

Also published in 1761 was a paper by John Hill, an English physician. In it he made the first causal link between substances in the environment and cancer when he described a relationship between tobacco snuff and nasal cancer. This brought about the awareness of carcinogens (chemical agents that have been demonstrated to cause cancer). In 1775, the English surgeon Sir Percivall Pott observed and noted a high rate of scrotal cancer among chimney sweepers. He postulated that it was caused by long-term exposure to the chemicals in the soot-soaked ropes worn as harnesses. His research led to studies that associated particular occupations with an increased risk of developing specific forms of cancer – the forerunner to the field of public health and cancer.

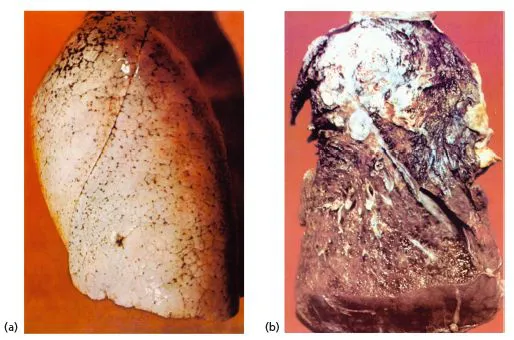

The use of microscopes demonstrated changes at a cellular level

The development of improved microscopes in the late nineteenth century allowed for more thorough examinations of cells and their activities than was previously possible. It was realized that cancer cells were different in both appearance and behavior from normal cells within the same tissue or organ (Figure 1.8). Early twentieth century accomplishments in the development of cell culture (an in vitro technique for studying the activity of cells in an organism under simulated physiological conditions1.1), new and improved diagnostic techniques, the discovery of chemical carcinogens, and the use of chemotherapy (powerful anticancer drugs) all had significant impacts upon the understanding and treatment of cancer.

MODERN DAY CANCER RESEARCH AND TREAT...