![]()

Part I

The Convertibles Market

![]()

1

Terminology

Gentlemen prefer bonds.

Andrew Mellon (US financier philanthropist, 1855–1937)

Convertible bonds have been around for more than a century. They are a spin-off from the traditional corporate bond market. The main difference is the fact that the buyer of convertible debt has the possibility to convert the convertible bond into shares of the issuing company. What makes these bonds challenging and at the same time interesting, is that their behaviour is on the crossroad of three asset classes: equity, fixed income and, to a lesser extent, currencies. The pricing and risk management of convertible bonds has benefited enormously from the advances in the equity derivatives scene and the advent of credit derivatives. In the equity derivatives discipline, for example, our understanding has moved a long way from the Black and Scholes breakthrough in 1973 to the introduction in the 1990s of the more advanced stochastic volatility models. The credit default swap market can be credited for bringing the concept of default intensity and recovery rates into the area of convertible bonds. This chapter provides a mandatory introduction into the standard terminology of this asset class. After reading this chapter, one will have mastered convertible slang.

1.1 THE PAYOFF

Hybrid securities are securities with both debt and equity characteristics. The most important family member of this asset class is the convertible bond. A convertible bond is a security in which the investor can convert the instrument into a predefined number of shares of the company that issued the bond. This conversion is, by default, not mandatory and is an option for the investor.

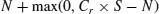

Convertible bonds are not new. We have to go back as far as 1881 to find the issue of the first convertible bond. The railroad magnate J.J. Hill needed an innovative way to finance one of his new projects because nobody was interested in buying any equity when he wanted to increase the capital in his railroad company. The convertible bond market has evolved a lot since this first issue more than a century ago, but the principle of mixing debt and equity in one single instrument remains the same. The final payoff of the convertible bond is written as:

The holder of this convertible has the right, at maturity, to swap the face value N of the bond for Cr shares with price S, where Cr is the conversion ratio. Hence, a simplified definition of a convertible bond is a bond with an embedded call option. Rewriting (1.1) and abstracting from the fact that the convertible might pay coupons illustrates this:

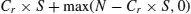

The above argument is only possible when the conversion is restricted to the maturity of the convertible bond. Actually, by put–call parity, holding a convertible bond is also economically the same as holding Cr shares combined with a European put option to sell these shares in return for the face value N of the convertible bond:

Some simplified valuation methods support this breakup. These methods try to value a convertible as a package consisting of a European option on a stock and a corporate bond. Convertible bonds are issued by corporates (the issuer) but we cannot simply categorize them as debt. They rank before the common stockholders, and their behaviour can move from being a pure bond to an equity-like security. All of this depends on the behaviour of the underlying common stock, into which the convertible can be converted. In the case when the conversion value (Cr × S) is high enough, the holder of the convertible (the investor) will exercise his or her conversion right. This could happen if the dividend yield earned on the shares is high enough compared to the coupon earned on the bond. On a non-dividend paying stock, conversion will not happen prior to maturity. A company issuing a convertible can be seen as selling shares on a forward basis. The above example is limited to the possibility of converting at maturity. Most convertibles are American-style in their conversion possibilities: converting the bond into shares is not limited to the maturity date only. Conversion can happen during a predefined conversion period (ΩConversion).

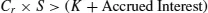

The value Cr × S is called the conversion value CV or parity Pa. Next to the conversion feature there is also a possibility for the bond to be called by the issuer. The issuer has, during a certain call period (ΩCall), the right to buy back the outstanding convertible security at a price K. This is the call price. In legal documents regarding convertibles, this is often called the early redemption amount. The moment the bond gets called, the investor can still convert into shares even when t ∉ ΩConversion. This is called a forced conversion and is different from (1.2), which stands for an optional conversion. After receiving a call notice from the issuer, the rational investor will convert if:

The conversion into common stock and the possibility of being called are the two basic building blocks present in most hybrid securities. In the next section, additional features will be discussed using a real-world example.

1.2 ADVANTAGES OF CONVERTIBLES

For both issuers and investors there are several advantages in issuing hybrid capital or investing in hybrid securities. According to the Modigliani–Miller theorem, the capital structure has no relevance. A company looking to raise capital should be indifferent to the way this capital is raised. Equity or debt, it doesn't really matter [78]. Their Nobel prize-winning paper is based on a perfect world with no taxes, and all information is available to everyone. A company cannot optimize its cost of capital by choosing a perfect mix of debt and equity. The reality is different however.

1.2.1 For the Issuer

Cost of capital consideration

Academic theory considers it a myth that the argument that the coupon on a convertible is less than the coupon on equivalent corporate debt, making the convertible the ideal instrument from a cost of capital point of view [28]. A treasurer or financial director of a company is not going to make the choice between issuing shares or corporate or convertible debt solely based on the annual coupon. If the share price rises in the future, the extra dilution after the conversion of the debt into shares would not maximize the value for the current shareholders. A company that is expecting a long-term rally on its shares would be better off issuing corporate debt. If the CFO is 100% certain that the share price is going to drop going forward, the shareholders would be better off having issued new share capital. But all of this is built on assumptions and wishful thinking. It is impossible to predict share prices. It would also imply that good companies issue debt and bad companies issue equity.

For growth companies, the lower coupon argument still stands, however. It might be a very good reason to opt for convertible debt as companies might run tight budgets in the first years after the issue date. A capital intensive growth company that is looking for a lighter interest rate charge will therefore prefer convertible debt over corporate debt. Table 1.1 provides for a handful of converts a comparison between the current yield1 on the convertible bond and the current yield on a corporate bond issued by the same issuer of the convertible. For each of the convertibles in the list a corporate bond issued by the same company is used as comparison. The current yield on the convertibles is clearly lower than the yield on corporate debt of the same issuer. The difference in yield is compensated by the embedded right to convert the convertible bond into shares at the discretion of the investor.

Table 1.1 Comparison of the current yield on some convertible and corporate bonds issued by the same...