![]()

Part One

Smart Strategy

![]()

Chapter 1.1

The Need for Smart Strategy

Why Strategy?

Without a goal in life, it is tough to achieve much. Mindless wandering rarely delivers great results. As the Cheshire Cat said in Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, “If you don't know where you are going, any road will get you there.”1

The goal of any business is to deliver superior sustainable performance. “Performance” means return on investment; firms are in business to make a profit. “Sustainable” means profit over the long term rather than to meet the next quarterly earnings targets. It's easy to deliver a short-term burst of profits by failing to invest for tomorrow and stealing from future performance. Delivering a sustainable stream of income is much harder. “Superior” means better than competitors; firms who always strive to win are less likely to be blindsided by competition, and more likely to survive and prosper. Winners also gain better access to resources (e.g. people, capital), increasing sustainability.

To deliver superior, sustainable performance firms need a good strategy. This requires good strategy formulation: the integration of choices on where and how to compete. It also depends on good strategy implementation: the marshalling of resources and integration of actions to deliver the strategy. Formulation and implementation both require good leadership to ensure that the right choices are made, the right assets are deployed and the right actions are taken.

Why Smart Strategy?

There is no such thing as strategy in isolation; it must be consistent with the competitive environment. This is always changing, so strategy must change too. Firms must constantly be steering purposefully in a winning direction; this is the definition of Strategic IQ. Those with moderate IQ keep up with the pack, but the smartest firms don't simply react to change; they drive it, shaping the competitive environment to their advantage. To do this, they need smart strategy.

Firms that fail to change their strategies in a timely fashion put themselves in grave danger. The longer the delay, the bigger the strategic problems become and the harder they are to fix. The more a firm invests in tactical responses that do not address the underlying strategic problems, the more resources are diverted from much-needed strategic change and the more the firm is distracted from the strategic issues it should be addressing.

It is easy to get caught in this trap. Sales and profits can continue to grow for many years before strategic weaknesses show through. Firms become complacent and defer expensive and painful changes until later. But once financial results collapse, shareholders have little patience with investing heavily in solving long-term problems; they want a quick fix. It becomes very difficult to make the necessary changes and the firm struggles on, squeezed between impatient investors and an increasingly hostile competitive environment until it finally fails. Far better to diagnose the disease early and treat it before it becomes critical; better still to avoid catching it at all. Part One: Smart Strategy of the book aims to help firms to do this.

In this chapter, we provide an overview of Part One, Ltd. We examine the pathology of strategic inertia and identify a number of levels of Strategic IQ. We start with firms demonstrating low IQ: they either don't know what strategy is or are incapable of changing it. This begs the question “What is Strategy?” We address this briefly. We then move on to firms with moderate IQ, which have recognized the need for strategy and are developing skills in strategy formulation and execution. Finally, we identify those with high IQ, constantly striving for better strategy. The remaining chapters in Part One examine each of these topics in more detail.

Low Strategic Intelligence

Developing and implementing a strategy is a non-trivial task, so it is not surprising that firms are reluctant to change once they have discovered one that works. But for some the problem is deeper than this; they've never had a strategy and don't know what one is; they deliver profitable growth without really knowing why. They are the strategically blind, blissfully ignorant and sit at the bottom of the Strategic IQ ladder.

It may seem amazing to some that firms without a strategy can do well, but it is often easy to grow sales and profits when there is little competition; all ships rise on a rising tide. When competitive pressure rises, the need for strategy becomes more apparent, but the blissfully ignorant don't know how to deal with it. And when profits are suffering, it is harder to invest time and money in figuring out what to do. The time to develop a strategy is before you realize you need one.

There are other forms of strategic blindness. Some firms play let's pretend and fool themselves that they have a strategy, using all the jargon, but what they are doing has precious little to do with building and sustaining competitive advantage. Then there are those with strategic amnesia; they once had a good strategy but have forgotten it and are now running on autopilot. All of these firms are strategically blind; they don't really know what their strategy is, so it is tough for them to know when to change it or how to do so. The challenge is to open their eyes to the need for strategy and build commitment to developing one.

The next rung on the ladder of low Strategic IQ is the peculiar behaviour of strategic denial. Such firms are wilfully blind; they have a clear strategy that has worked for them in the past and they refuse to give it up despite the fact that they can see the need for change. Some try to ignore the data, like the proverbial ostrich with its head in the sand; others accept it but do nothing, awaiting their fate like a bunny in the headlights. Others exhaust themselves with tactical diversions such as overhead cost reductions and reorganizations in order to drive short-term profits rather than fix the long-term problem. Firms caught in denial must be encouraged to confront the fact that they have a strategic problem and accept that they must now move on to survive. They must also put mechanisms in place to prevent this behaviour from being repeated.

Strategically incompetent firms are one rung up on the IQ ladder from those who are in strategic denial, because they admit they have a strategic problem but they don't have the competence to solve it. Some firms are lost in the dark; everyone can “feel” the problem, but they don't know what it is. Others find themselves squabbling because there are a wide range of strongly held views on the issue and no real agreement on how to proceed. Some cannot agree on the problem, others on a solution. In either case, this is probably just as well since incompetence leads to poorly framed problems and ineffective solutions. In the absence of understanding and alignment, all these firms continue with the old strategy, or invest excessive effort in tactical palliatives. The firms in greatest danger are those that agree on the problem and on the solution, but don't really know what they are doing. They march off in the hope of victory even though they are headed in the wrong direction.

There is a temptation amongst the incompetent to hire consultants to develop a strategy for them. In a changing world, this doesn't solve the long-term problem because the strategy will soon need to change again. It merely creates dependence, effectively outsourcing to advisors the critical decisions on how to compete. Strategically incompetent firms must commit to building the processes and the skills needed to formulate and implement strategy for themselves. Making this commitment is the first step to moderate strategic intelligence.

The challenges of low Strategic IQ and how firms can move towards moderate strategic intelligence are discussed in more detail in Chapter 1.2: Low Strategic Intelligence.

What is Strategy?

To commit to building strategic competence, firms must recognize that strategy is important and understand what it involves.

The objective of strategy is to deliver superior sustainable performance. Firms that achieve this attract more and better resources (e.g. people, investment). This makes them even more sustainable – a virtuous circle. Those that do not deliver this often wither and die. The importance of the distinction should not be lost on any firm committed to longevity.

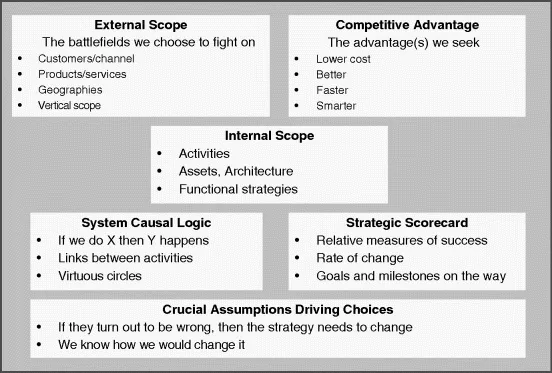

The principles of how a company intends to deliver superior sustainable performance are captured in its strategic business model (Figure 4).2 This summarizes the choices the firm has made about where to compete, what competitive advantage it seeks, what assets and activities it will invest in to deliver that advantage (its internal scope) and how it intends to organize these assets to do so.

The choice of where to compete is important because some businesses and business segments are more attractive than others. Firms must pick the right battlefields.3

But wherever they compete, they are likely to come across competitors, so they must make sure they build an advantage that will help them to win, to deliver superior profits. The two most important static advantages are lower cost and differentiation.4 For firms with lower costs, it is relatively clear why they can make more money. Differentiation is more subtle; it means better, as defined by the customer. And to make more profits, it must also support a price premium that exceeds any extra costs involved.

Faster and smarter are two dynamic advantages. Firms that are faster to reposition to attractive battlefields or increase static advantages have an edge.5 They can make superior profits until the competition catches up. Smarter companies look to exploit the inertia of competitors and do things that are harder to copy.6 They also look for pathways that give them more options for the future.7

A firm's ability to build advantage will depend on the assets it has at its disposal and how it organizes these assets.8 It may choose to invest in some activities and let third parties perform others. The objective is to configure to deliver the best returns.

The strategic business model documents the causal logic of the strategy, explaining the linkages between the drivers of advantage and the level of advantage expected. For instance, a doubling in plant scale might drive unit costs down by 15%. The logic also identifies the critical interdependencies between activities to reveal the effects of each activity on overall advantage. For example, for many years, Wal-Mart used to spend more on IT than its competitors, but the overall effect of this was to reduce costs because it brought the cost of many other activities down.

In addition to the logic, firms require strategic metrics9 showing the size of their advantage relative to competitors, the rate at which this is changing to see who is changing faster, the goals the firm has set itself and milestones along the way. Metrics help to test the veracity of the model and to ensure that everything is on track.

Ideally, the logic of a strategic business model should incorporate positive feedback loops or “virtuous circles”, driving ever-greater advantage.10 For instance, a firm might cut prices to increase...