![]()

1

Ubiquitous Computing: Basics and Vision

1.1 Living in a Digital World

We inhabit an increasingly digital world, populated by a profusion of digital devices designed to assist and automate more human tasks and activities, to enrich human social interaction and enhance physical world1 interaction. The physical world environment is being increasingly digitally instrumented and strewn with embedded sensor-based and control devices. These can sense our location and can automatically adapt to it, easing access to localised services, e.g., doors open and lights switch on as we approach them. Positioning systems can determine our current location as we move. They can be linked to other information services, i.e., to propose a map of a route to our destination. Devices such as contactless keys and cards can be used to gain access to protected services, situated in the environment. Epaper2 and ebooks allow us to download current information onto flexible digital paper, over the air, without going into any physical bookshop. Even electronic circuits may be distributed over the air to special printers, enabling electronic circuits to be printed on a paper-like substrate.

In many parts of the world, there are megabits per second speed wired and wireless networks for transferring multimedia (alpha-numeric text, audio and video) content, at work and at home and for use by mobile users and at fixed locations. The increasing use of wireless networks enables more devices and infrastructure to be added piecemeal and less disruptively into the physical environment. Electronic circuits and devices can be manufactured to be smaller, cheaper and can operate more reliably and with less energy. There is a profusion of multi-purpose smart mobile devices to access local and remote services. Mobile phones can act as multiple audio-video cameras and players, as information appliances and games consoles.3 Interaction can be personalised and be made user context-aware by sharing personalisation models in our mobile devices with other services as we interact with them, e.g., audio-video devices can be pre-programmed to show only a person’s favourite content selections.

Many types of service provision to support everyday human activities concerned with food, energy, water, distribution and transport and health are heavily reliant on computers. Traditionally, service access devices were designed and oriented towards human users who are engaged in activities that access single isolated services, e.g., we access information vs we watch videos vs we speak on the phone. In the past, if we wanted to access and combine multiple services to support multiple activities, we needed to use separate access devices. In contrast, service offerings today can provide more integrated, interoperable and ubiquitous service provision, e.g., use of data networks to also offer video broadcasts and voice services, so-called triple-play service provision. There is great scope to develop these further (Chapter 2).

The term ‘ubiquitous’, meaning appearing or existing everywhere, combined with computing to form the term Ubiquitous Computing (UbiCom) is used to describe ICT (Information and Communication Technology) systems that enable information and tasks to be made available everywhere, and to support intuitive human usage, appearing invisible to the user.

1.1.1 Chapter Overview

To aid the understanding of Ubiquitous Computing, this introductory chapter continues by describing some illustrative applications of ubiquitous computing. Next the proposed holistic framework at the heart of UbiCom called the Smart DEI (pronounced smart ‘day’) Framework UbiCom is presented. It is first viewed from the perspective of the core internal properties of UbiCom (Section 1.2). Next UbiCom is viewed from the external interaction of the system across the core system environments (virtual, physical and human) (Section 1.3). Third, UbiCom is viewed in terms of three basic architectural designs or design ‘patterns’: smart devices, smart environments and smart interaction (Section 1.4). The name of the framework, DEI, derives from the first letters of the terms Devices, Environments and Interaction. The last main section (Section 1.5) of the chapter outlines how the whole book is organised. Each chapter concludes with exercises and references.

1.1.2 Illustrative Ubiquitous Computing Applications

The following applications situated in the human and physical world environments illustrate the range of benefits and challenges for ubiquitous computing. A personal memories scenario focuses on users recording audio-video content, automatically detecting user contexts and annotating the recordings. A twenty-first-century scheduled transport service scenario focuses on the transport schedules, adapting their preset plans to the actual status of the environment and distributing this information more widely. A foodstuff management scenario focuses on how analogue non-electronic objects such as foodstuffs can be digitally interfaced to a computing system in order to monitor their human usage. A fully automated foodstuff management system could involve robots which can move physical objects around and is able to quantify the level of a range of analogue objects. A utility management scenario focuses on how to interface electronic analogue devices to an UbiCom system and to manage their usage in a user-centred way by enabling them to cooperate to achieve common goals.

1.1.2.1 Personal Memories

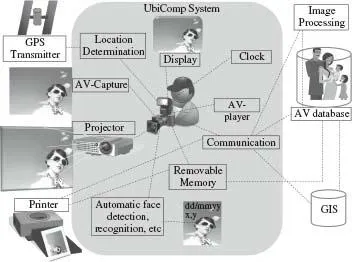

As a first motivating example, consider recording a personal memory of the physical world (see Figure 1.1). Up until about the 1980s, before the advent of the digital camera, photography would entail manually taking a light reading and then manually setting the aperture and shutter speed of the camera in relation to the light reading so that the light exposure on to a light-sensitive chemical film was correct.4 It involved manually focusing the lens system of the camera. The camera film behaved as a sequential recording media: a new recording requires winding the film to the next empty section. It involved waiting for the whole film of a set of images, typically 12 to 36, to be completed before sending the recorded film to a specialist film processing company with specialist equipment to convert the film into a specialist format that could be viewed. The creation of additional copies would also require the services of a specialist film processing company.

A digital camera automatically captures a visual of part of the physical world scene on an inbuilt display. The use of digital cameras enables photography to be far less intrusive for the subject than using film cameras.5 The camera can autofocus and auto-expose recorded images and video so that recordings are automatically in focus and selected parts of the scene are lit to the optimum degree. The context of the recording such as the location and date/time is also automatically captured using inbuilt location and clock systems. The camera is aware that the person making a recording is perhaps interested in capturing people in a scene, in focus, even if they are off centre. It uses an enhanced user interface to do this which involves automatically overlaying the view of the physical world, whether on an inbuilt display or through a lens or viewfinder, with markers for parts of the face such as the eyes and mouth. It then automatically focuses the lens so faces are in focus in the visual recording.

The recorded content can be immediately viewed, printed and shared among friends and family using removable memory or exchanged across a communications network. It can be archived in an external audio-visual (AV) content database. When the AV content is stored, it is tagged with the time and location (the GIS database is used to convert the position to a location context). Image processing can be used to perform face recognition to automatically tag any people who can be recognised using the friends and family database. Through the use of micro electromechanical systems (MEMS (Section 6.4) what previously needed to be a separate decimetre-sized device, e.g., a projector, can now be inbuilt. The camera is networked and has the capability to discover other specific types of ICT devices, e.g., printers, to allow printing to be initiated from the camera. Network access, music and video player and video camera functions could also be combined into this single device.

Ubiquitous computing (UbiCom) encompasses a wide spectrum of computers, not just devices that are general purpose computers,6 multi-function ICT devices such as phones, cameras and games consoles, automatic teller machines (ATMs), vehicle control systems, mobile phones, electronic calculators, household appliances, and computer peripherals such as routers and printers. The characteristics of embedded (computer) systems are that they are self-contained and run specific predefined tasks. Hence, design engineers can optimise them as follows. There is less need for full operating system functionality, e.g., multiple process scheduling and memory management and there is less need for a full CPU, e.g., the simple 4-bit microcontrollers used to play a tune in a greeting card or in a children’s toy. This reduces the size and cost of the product so that it can be more economically mass-produced, benefiting from economies of scale. Many objects could be designed to be a multi-function device supporting AV capture, an AV player, communicator, etc. Embedded computing systems may be subject to a real-time constraint, real-time embedded systems, e.g., anti-lock brakes on a vehicle may have a real-time constraint that brakes must be released within a short time to prevent the wheels from locking.

ICT Systems are increasing in complexity because we connect a greater diversity and number of individual systems in multiple dynamic ways. For ICT systems to become more useful, they must in some cases become more strongly interlinked to their physical world locale, i.e., they must be context-aware of their local physical world environment. For ICT systems to become more usable by humans, ICT systems must strike the right balance between acting autonomously and acting under the direction of humans. Currently it is not possible to take humans completely out of the loop when designing and maintaining the operation of significantly complex systems. ICT systems need to be designed in such a way that the responsibilities of the automated ICT systems are not clear and the responsibilities of the human designers, operators and maintainers are clear and in such a way that human cognition and behaviour are not overloaded.

1.1.2.2 Adaptive Transport Scheduled Service

In a twentieth-century scheduled transport service, timetables for a scheduled transport service, e.g., taxi, bus, train, plane, etc. to pick up passengers or goods at fixed or scheduled point are only accessible at special terminals and locations. Passengers and controllers have a limited view of the actual time when vehicles arrive at designated way-points on the route. Passengers or goods can arrive and wait long times at designated pick-up points. A manual system enables vehicle drivers to radio in to controllers their actual position when there is a deviation from the timetable. Controllers can often only manually notify passengers of delays at the designated pick-up points.

By contrast, in a twenty-first-century scheduled transport service, the position of transport vehicles is determined using automated positioning tec...