![]()

Part One

Basics of Asset Securitization

![]()

Chapter 1

Asset Securitization: Concept and Market Development

The concept and market practice of asset securitization started in 1970, when mortgage bankers pooled their newly originated residential mortgages and issued residential mortgage-backed securities. By issuing residential mortgage-backed securities, mortgage bankers were able to raise funds more efficiently in the capital market to finance their originations of residential mortgages.1 It took only 20 years for the asset securitization market to become the largest sector in the U.S. capital market, with the outstanding balance exceeding one trillion dollars. In the early development of the asset securitization market, residential mortgages were the only type of underlying assets that were being securitized. Since the mid-1980s, a great variety of financial assets that had predictable and steady future receivable cash flows have been utilized as the underlying assets for securitization.

This chapter will first discuss the basic concept of asset securitization. It will then present the development history of the asset securitization market in the United States over the past 40 years.

Basic Concept of Asset Securitization

Asset securitization is an innovative way for lenders to raise funds in the capital market by selling the future receivable cash flows of their assets.2 The cash flows are sold in the form of securities that are backed by the cash flows of the very assets sold. The securities are therefore called asset-backed securities. This method of financing differs from the traditional means of raising funds by attracting deposits or borrowing in the form of loans. It is also different from issuing debt or equity securities (bonds or stocks) to obtain funds in the capital market.

Issuers of asset-backed securities are mostly originators of the assets backing the securities. These assets can be a wide variety of residential or commercial mortgages, consumer loans, commercial leases, or any financial instruments that have predictable and stable receivable cash flows. In recent years, there have been new and popular asset-backed securities that are supported by assets that are corporate bonds, commercial and industrial loans, or even asset-backed securities themselves.

Since asset-backed securities are issued by lenders through the mechanism of structuring future receivable cash flows of the underlying assets to finance their funding needs, the securities are also called structured finance securities. From an accounting point of view, the issuance of asset-backed securities is considered an asset sale. This differs from the issuance of bonds, which is debt financing by corporations, the various levels of government, or authorities.

Specifically, by issuing an asset-backed security to raise funds to finance the origination of loans, the financing has the following five salient features:

- The asset-backed security is issued through a special purpose entity.

- The accounting treatment of issuing an asset-backed security is asset sale rather than debt financing.

- An asset-backed security requires the servicing of the underlying assets for the investor.

- The credit of the asset-backed security is derived primarily from the credit of the underlying assets (the collateral).

- There is invariably a need of credit enhancement for the asset-backed security.

At the outset, it is critical that several basic terms of asset securitization are clarified to avoid possible confusion in future discussions. Throughout this book, the presentation and the analysis, unless specifically noted, are from the viewpoint of the lender, who is a loan originator. The originator is the one who originates the loans that are pooled as the underlying assets for the issuance of asset-backed securities in the asset securitization transaction. Therefore, the term originator is synonymous with the term lender. The two terms are used in the book interchangeably. Further, since asset securitization is primarily enabling those originators to use their newly originated or existing loans to obtain funds, the loans are really their assets (although from the point of view of the borrowers, they are debts). Thus, the terms loans and assets in the context of structured finance are also synonymous. They are interchangeable terms. The issuer of asset-backed securities is mostly an entity that is set up by the originator of the underlying assets. So, while the originator and the issuer are legally two different entities, they are economically the same or very closely related business entities.

Special Purpose Entity

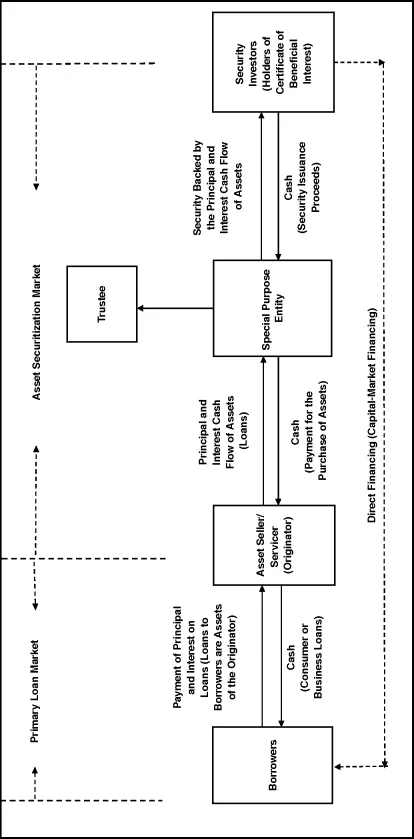

A special purpose entity (SPE) is a unique feature of asset securitization.3 Alternatively, an SPE is also referred to as a special purpose vehicle (SPV) or a special purpose trust (SPT). Basically, an SPE is a trust that is set up by the originator for the purpose of purchasing the loans it originates and issuing in the capital market a certificate of beneficial interest, for which the cash flows are backed solely by the cash flow of loans purchased from the originator (see Figure 1.1). Actually, the purchase of loans and the issuance of the certificate of beneficial interest take place simultaneously. They are two parts of a transaction. The SPE, on the one hand, raises the funds in the capital market by issuing the asset-backed security; and on the other hand, it uses the very issuance proceeds to pay for the purchase of the underlying assets. The holder of the certificate of beneficial interest is generically called the investor of the asset-backed security.

From a balance-sheet point of view, the SPE has no assets other than those purchased from the originator, and no liabilities other than those of the asset-backed security it issues. With this special and strict asset–liability structure, the cash flows of the assets are matched by those of the liabilities. From the accounting and legal points of view, the SPE is considered bankruptcy-remote. Asset securitization is also called structured finance, because it is done through a special legal structure of the SPE and the interest and principal payment of the security it issues is through the structuring of the projected future receivable cash flows from the underlying assets. Structured finance is a formal and generic term for asset securitization. The term structured finance is often used to differentiate from corporate finance. Colloquially, however, the term asset securitization is more often used to describe precisely the process of pooling assets for the issuance of an asset-backed security. To further simplify the description of asset securitization, it sometimes is just called securitization.

Asset Sale versus Debt Financing

One great advantage of asset securitization is that it is an effective way of managing the balance sheet by the originator through the selling of its newly originated or existing loans to raise funds. This way of financing enables the originator to collect the present value, at the prevailing market price, of the stream of the future receivable cash flows of their assets. Asset securitization, therefore, is not a debt financing and the funding has no consequence of expanding the issuer's balance sheet. Further, by selling assets, the originator does not rely on attracting deposits or borrowing from other financial institutions to fund the origination of the assets, both of which will expand the liability side of the balance sheet. Actually, it can be said that when a lender raises funds through asset securitization, the financing could even have the effect of shrinking the lender's balance sheet if it elects to use the issuance proceeds to pay down liabilities (this being the case when the lender sells existing loans on its portfolio). By contrast, a lender raising funds through deposits, borrowing, issuing debt or equity securities to fund the origination of loans would have the consequence of expanding its balance sheet.

The Requirement of Servicing

The function of servicing is unique for asset-backed securities because the sole source of the interest and principal payments of the securities is supported entirely by the future cash flows of the underlying assets. The servicing function is performed by a servicer, who often is the originator and also the seller who sells the very assets to the SPE. Primarily, the servicer performs the servicing function by collecting the interest and principal cash flows generated from the underlying assets and then passing them, through the SPE, to the investor (holder of certificate of beneficial interest). Other important elements of the servicing function include working with delinquent borrowers, disposing of defaulted assets, and providing timely and accurate cash-flow reports to investors.

In the early days of the legal structure of the SPE, which was a grantor trust, the servicing function was passive in that the servicer was required not to touch the cash flow generated from the underlying assets other than just passing them on to the investor. This requirement was made necessary so that the Internal Revenue Service would see through the SPE, not levying an income tax at the SPE level on the interest cash flow generated from the underlying assets. The income tax liability will fall on the investor, who is the ultimate owner of the assets underlying the asset-backed securities. It stands to reason that if the tax on interest income to the SPE were to be levied while the interest income to the investor is also taxed, there would be income taxes on two levels of the transaction. This double taxation would completely nullify the economic benefits intended for securitization.

Under this passive management requirement, all the servicer was required to do was simply pass the cash flows onto the investor. The servicer could not manage the cash flows to earn incremental yield for the trust by reinvesting the interim cash flow (the cash flow the SPE owns temporarily between the time it was collected by the servicer and the time it was distributed to the certificate holder). Nor was the servicer permitted to allocate the principal cash flow of the underlying assets to satisfy the varying maturity preferences of the different types of investors. Later on, new legislation permitted active management of the cash flow of the underlying assets. It allowed the servicer to allocate the cash flow, without encountering tax consequences, by prioritizing the principal payment of the underlying assets to investors according to maturity and credit-risk preferences. Also, the servicer was allowed to manage the interim cash flow to enhance the income of the trust by purchasing short-term money market instruments with the interim cash flow.

As will be explained in later chapters, the ability of the servicer to allocate cash flows is critically important in the development of new types of asset-backed securities. It allowed the innovative creation of maturity tranching and credit tranching of the cash flows of the underlying assets. Issuers were allowed to issue asset securitization securities in various maturity classes and credit-risk classes.

In comparison with asset-backed securities, corporate or government bonds do not need servicers. This is because the interest and principal payment of these obligations are paid out of the issuers' earnings or tax revenues. The cash flows of the liabilities are not matched by the cash flows of any of their assets.

Credit of the Underlying Assets

Since the interest and principal cash flow of an asset-backed security come solely from its underlying assets, the credit risk of the security is derived primarily from the credit risk of the underlying assets. (As will be explained in later chapters, the credit risk, or simply the credit, of a borrowing entity or a debt instrument refers to the likelihood of the borrower defaulting on its debt. The likelihood of default is assessed publicly by credit rating agencies. According to credit rating agencies, the incidence of default is defined as the borrower failing to make timely payment of interest and/or the repayment of principal of the debt. A high credit rating, or a strong credit, would mean a low probability of default. Conversely, a low credit rating, or a weak credit, suggests a high probability of default.) More important, the credit of the assets is highly dependent on economic conditions. In a prosperous economy, the underlying assets would perform strongly with less frequent incidences of default. In a depressed economy, however, the underlying asset would have a weak credit performance and the incidences of default would become more frequent.

This feature contrasts sharply with the credit determinant of a debt obligation of a corporation or a government entity. The credit strength of a corporate debt is first and foremost dependent on the management of the corporation. A well-managed corporation is likely to have a stronger credit because it is more likely to be financially healthy with a greater earning potential. This would enable the corporation to service its debt in various economic environments. Conversely, the credit o...