- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Advances in Enzymology and Related Areas of Molecular Biology, Volume 77

About this book

This book covers important advances in enzymology, explaining the behavior of enzymes and how they can be utilized to develop novel drugs, synthesize known and novel compounds, and understand evolutionary processes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Advances in Enzymology and Related Areas of Molecular Biology, Volume 77 by Eric J. Toone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biochemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Structure and Mechanism of RND-Type Multidrug Efflux Pumps

I. Introduction

It has long been known that gram-negative bacteria are usually much more resistant than gram-positive bacteria to the actions of antibiotics and chemotherapeutic agents. The cells of the former group are surrounded by an extra membrane layer, the outer membrane (OM), and it was suspected that this additional membrane layer acted as a general barrier for the influx of agents. Indeed, the nonspecific diffusion channels of OM, the porins, limit the influx of small hydrophilic agents, because their channels are quite narrow (7 by 11 Å in the Escherichia coli OmpF porin) (1, 2). In addition, the lipid bilayer domain of the OM is unusual in its extreme asymmetry by having the outer leaflet composed nearly exclusively of lipopolysaccharides containing only saturated fatty acid chains (3), and the very low fluidity of this outer leaflet decreases the spontaneous permeation rates of hydrophobic probe molecules by nearly two orders of magnitude compared with conventional phospholipid bilayers containing many unsaturated fatty acid residues (4). Nevertheless, when the permeability coefficients of β-lactams across E. coli OM were measured, even the slowest-penetrating compounds were found to equilibrate across the outer membrane usually within a minute, that is, in a time span that is much shorter than the generation time of E. coli (5), in part because the surface-to-volume ratio is very high in these small bacterial cells. It was thus clear that the OM barrier alone cannot generate significant levels of resistance, and another major process must work synergistically with this barrier (5). With β-lactams, the ubiquitous periplasmic β-lactamases can fulfill this role. However, with other classes of antibiotics, the nature of this second process remained obscure until the constitutive multidrug efflux pumps were found to be widespread in gram-negative bacteria and to act synergistically with the OM barrier (6, 7).

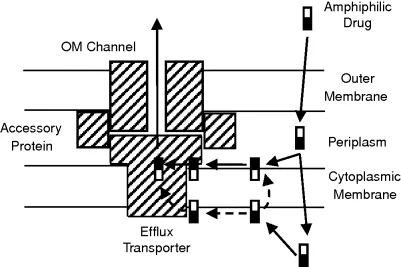

Gram-negative bacteria usually contain multidrug efflux pumps belonging to several families, such as ABC (ATP-binding cassette), SMR (small multidrug resistance), MFS (major facilitator superfamily), MATE (multiple antibiotic and toxin extrusion), and RND (resistance–nodulation–division) (8–10). Among these, most are pumps located in the cytoplasmic membrane and must pump out drugs rapidly into the periplasm because the drugs can penetrate back into cytosol frequently by spontaneous diffusion. Only the RND pumps (and a few exceptional pumps belonging to other families) exist in a tripartite form traversing both the OM and the inner membrane, in a manner first suggested by Wandersman and co-workers for a protein-secreting apparatus of gram-negative bacteria (11). This complex involves, in addition to the RND pump protein located in the inner membrane, an outer membrane channel such as TolC of E. coli (belonging to OMF [outer membrane factor] family (12)), and a periplasmic adaptor protein (belonging to the MFP [membrane fusion protein] family (13)). As shown in Figure 1, this construction allows the bacteria to pump out drug molecules directly into the external medium. This is a huge advantage for bacteria, because the drug in the medium has to cross the low-permeability OM in order to reenter the cells, in contrast to the drug molecules in the periplasm, which can easily penetrate the high-permeability inner membrane. Thus, the tripartite RND pumps are expected to produce drug resistance very effectively by working synergistically with the outer membrane barrier (6, 7).

Figure 1 Early schematic view of the tripartite pump complex. Note that amphiphilic drugs (empty and solid rectangles represent hydrophobic and hydrophilic parts of the molecule) are hypothesized to be captured from the periplasm–plasma membrane interface or possibly from the cytosol (or the cytosol–membrane interface). For the latter process, two possible pathways are envisaged (dashed arrows): Either the substrate is flipped over to the outer surface of the membrane first and then follows the regular periplasmic capture pathway, or it follows a different capture pathway from the cytosol. For the AcrAB–TolC system, the efflux transporter corresponds to AcrB, the accessory protein to AcrA, and the OM channel to TolC. [Modified from (7).]

Wild-type strains of most gram-negative bacteria are resistant to most lipophilic antibiotics (for E. coli they include penicillin G, oxacillin, cloxacillin, nafcillin, macrolides, novobiocin, linezolid, and fusidic acid), and this “intrinsic resistance” was often thought to be caused by the exclusion of drugs by the outer membrane barrier. Indeed, breaching the outer membrane barrier does sensitize E. coli cells to the drugs just mentioned (14). However, inactivation of the major and constitutively expressed RND pump AcrB also makes the bacteria nearly completely susceptible to these agents [the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of a lipophilic penicillin, cloxacillin, goes down from 512 μg/mL in the wild type to only 2 μg/mL (15)] even in the presence of the intact outer membrane barrier. Thus, the characteristic intrinsic resistance of gram-negative bacteria owes as much to the RND pumps as to the outer membrane barrier.

Since some tripartite pumps give resistance to drugs that cannot penetrate the inner membrane, such as the dianionic compound carbenicillin, they were proposed to be able to capture drug molecules from the periplasm (6, 7). Finally, in order to produce significant levels of drug resistance, the drugs that were pumped out into the periplasm by the simple pumps located in the inner membrane need to be captured and then extruded across the OM into the medium by tripartite RND pumps (16, 17). For example, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the expression of a simple tetracycline pump TetA produces only a very modest degree of resistance (MIC = 32 μg/mL) in the absence of the main tripartite pump MexB–MexA–OprM, but MIC is raised up to 512 μg/mL if the tripartite pump is, in addition, expressed at the normal, constitutive level. That the high resistance is not due to the pumping of tetracycline by the tripartite pump alone is seen from the fact that the tripartite pump, in the absence of TetA, produces an MIC of only 4 μg/mL (16). Thus, these two types of pumps appear to act in a truly synergistic manner.

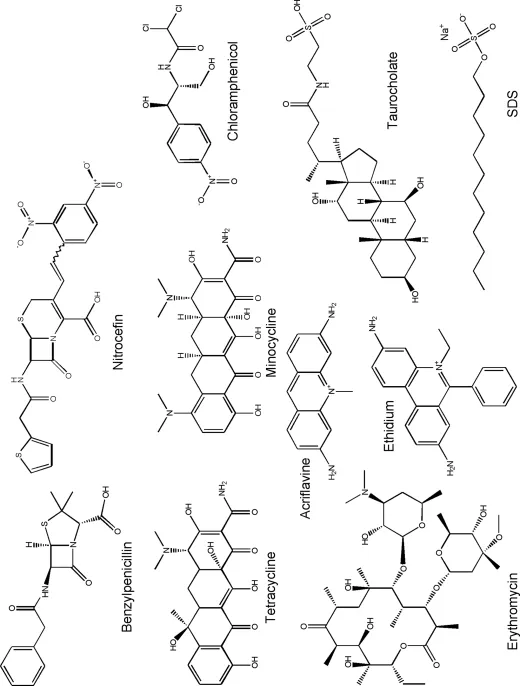

The first example of an RND pump that functions as a multidrug exporter was identified in 1993 (18); this was AcrB (called AcrE in that paper) in E. coli. The immediately upstream gene, acrA, was known to be involved in acriflavine resistance, but the mechanism was thought to be the decreased permeability of the envelope through the global chemical modification of its components. We showed that acriflavine penetrates rapidly across OM in both the wild-type and acrAB-inactivated strain, yet accumulates at a much higher level in the cells of the latter. We also noted the similarity of the AcrB sequence to CzcA, a divalent cation efflux pump, and proposed that AcrB functions by actively pumping out acriflavine, not by strengthening the passive permeability barrier of OM. The extremely wide substrate specificity of this pump was indicated by the fact that inactivation of the acrAB genes made E. coli hypersusceptible not only to several dyes but also to detergents (such as SDS, Triton X-100, and bile salts) and to a wide range of antibiotics, including macrolides, β-lactams, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, fusidic acid, and novobiocin (but not aminoglycosides) (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Examples of substrates for the AcrB pump.

At about the same time, Poole and co-workers (19) found that P. aeruginosa mutants capable of growth in the presence of an iron chelator, α,α′-dipyridyl, overproduced an outer membrane protein (OprM, called OprK in the paper), and that the oprM gene was a part of an operon with upstream genes mexAB that are homologous to acrAB. Indeed, the inactivation of these genes made the organism hypersusceptible to chloramphenicol, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, and streptonigrin. Meanwhile, our studies on clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa whose β-lactam resistance could not be explained fully by the combination of OM barrier and the periplasmic β-lactamase showed that unidentified multidrug efflux pump(s) are overexpressed in these strains, leading to simultaneous resistance to a large number of agents (20, 21). The most likely candidate for this pump was found to be the MexAB–OprM, the major constitutive RND multidrug efflux transporter of P. aeruginosa, through collaboration with the Poole laboratory (22). MexAB–OprM extrudes not only fluoroquinolones, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline, but also novobiocin and a number of β-lactam antibiotics. These studies also gave the first indication that the pump functions as a tripartite complex, as mexA, mexB, and oprM genes comprised a single operon; in E. coli, the outer membrane channel TolC is coded elsewhere on the chromosome (23). Importantly, each of these three component proteins is essential for drug efflux, and the absence of even one component makes the entire complex totally nonfunctional (18, 19, 24). To this day, AcrB and MexB have been the most intensively studied RND drug transporters in bacteria and have served as the prototype for biochemical and structural studies of such pumps.

Some of the observations made in this early period were important in formulating our concepts on the function of RND drug efflux transporters.

1. Some β-lactam compounds, such as carbenicillin and ceftriaxone, which contain multiple charged groups and therefore cannot diffuse across the inner membrane, as verified experimentally, are nevertheless very good substrates of MexAB–OprM (21) and AcrAB– TolC (15). This observation indicates that the RND pumps are capable of capturing substrates from the periplasm (6, 7, 21). The periplasmic capture also fits with the observation that the same pump can catalyze the efflux of substrates with diverse charges: uncharged, anionic, cationic, or zwitterionic (7). Export of these substrates from cytosol will generate different effects on membrane potential, which may be difficult to deal with.

2. Although the pumps often handle a very wide range of substrates, they all seem to have a significant lipophilic portion (7, 15). This observation led to a hypothesis that many substrates become partially partitioned, from the periplasm into the outer leaflet of the inner membrane (see Figure 1), before being captured by the pump (7). This association with the membrane surface would involve an energetic cost in terms of decreased entropy, but a similar phenomenon is well known to occur with the interaction of amphiphilic anesthetics with lipid bilayers (25). An alternative interpretation of the requirement of lipophilic domain in the ligands, however, might be that hydrophobic interaction plays a predominant role in the binding of substrates at the binding pocket of the pump (see Section IV).

Finally, it should be mentioned that the tripartite architecture is not completely limited to RND pumps. In E. coli, an MFS efflux pump EmrB is known to form a tripartite structure together with the periplasmic adaptor EmrA and the outer membrane channel TolC (26), and to pump out weakly acidic or largely uncharged substrates, such as the proton uncoupler carbonyl cyanide m-chloropheny...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contributors

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Structure and Mechanism of RND-Type Multidrug Efflux Pumps

- Chapter 2: Efflux Pumps of Gram-Negative Bacteria: Genetic Responses to Stress and the Modulation of Their Activity by pH, Inhibitors, and Phenothiazines

- Chapter 3: Efflux Pumps of the Resistance–Nodulation–Division Family: A Perspective of Their Structure, Function, and Regulation in Gram-Negative Bacteria

- Chapter 4: The MFS Efflux Proteins of Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria

- Chapter 5: Efflux Pumps as an Important Mechanism for Quinolone Resistance

- Chapter 6: Xenobiotic Efflux in Bacteria and Fungi: A Genomics Update

- Chapter 7: A Survey of Oxidative Paracatalytic Reactions Catalyzed by Enzymes That Generate Carbanionic Intermediates: Implications for ROS Production, Cancer Etiology, and Neurodegenerative Diseases

- Color Plates

- Author Index

- Subject Index