![]()

Section VI

Structural Approaches

![]()

Restoring Habitat Hydraulics With Constructed Riffles

Robert Newbury

Newbury Hydraulics, Okanagan Centre, British Columbia, Canada Canadian Rivers Institute, University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada

David Bates

FSCI Consultants, Sechelt, British Columbia, Canada

Karilyn Long Alex

Okanagan First Nations Fisheries Department, Westbank, British Columbia, Canada

Riffles and rapids may be added to channels for a variety of purposes, including increasing hydraulic complexity, stabilizing mobile bed streams, increasing aquatic habitat, or restoring fish passage. To increase hydraulic complexity, there are several options for introducing locally varied hydraulic conditions through the creation of riffles, rapids, runs, and pools. This involves increasing the frequency of transitions between several conditions of uniform, gradually varied and rapidly varied flow. To improve fish passage, riffles and rapids are normally designed as fish-passable hydraulic structures, often replacing traditional fixed drop structures or low dams in channelized streams. The provision of more diverse hydraulics and fish access may be a project objective, but the intricacies of specific aquatic habitat types are beyond commonly used one-dimensional open channel hydraulic equations. Consequently, reliance is placed on mimicking the hydraulics of preferred habitats surveyed in natural reference streams. The hydraulics observed in several preferred aquatic habitat types are broadly summarized, and a design method for riffles, runs, and pools with six project examples is presented.

1. HYDRAULICS AND HABITATS

Rapidly varying flows occur in streams at man-made structures, variations in bed topography, large roughness elements, or changes in channel shape. The local velocity and trajectory of flow is shaped by the flow boundaries and often by discrete cells of water moving within one another. Contrary to the uniform flow assumptions, a surprising amount of water may flow both in a cross-stream and upstream direction, such as when fast water enters a slowly moving pool (Figure 1). Energy losses result primarily from turbulent contraction, expansion, and deceleration. These conditions occur over such a short reach that frictional losses on the boundaries are generally ignored for design purposes.

Rapidly varied flow conditions are the focus of this chapter. For a full treatment of open channel hydraulics and hydraulic structures, readers may refer to several historic and recent sources: introductory concepts [Brater and King, 1976; Kay, 1998], open channel hydraulics [Chow, 1959; Chanson, 1999], fluvial processes [Leliavsky, 1966; Chang, 1988], and habitat hydraulics [Vogel, 1981; Allan, 1995].

Figure 1. In this short reach at the head of a pool, two thirds of the flow directions are upstream or across the channel in two back eddies on either side of the channel and in the “horseshoe vortex” formed behind the boulder. Aeration occurs as the rapid flow penetrates the slower moving pool water, carrying air under the surface that emerges as noisy bubble-popping white water. This is the only source of flowing water sound and a sure indicator of rapidly varying flow.

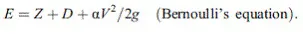

The state of the flow is defined by how the potential and kinetic energy components are partitioned [see Chow, 1959, chapter 1]. The potential and kinetic energy components are expressed in an equation named for Daniel Bernoulli (1700–1782) in recognition of his founding hydraulic concepts by Euler (1707–1783) [Rouse and Ince, 1957] where

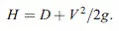

Applied to stream channels, E is the sum of all of the energy of the flow at that point in the channel, Z is the elevation of the channel bed above a determined datum (m), D is depth of flow (m), V is the mean velocity (m s-1), g is the acceleration due to gravity (9.8 m s-2), and α is an adjustment factor for cross-section changes in the short reach (assumed to be 1.0 in this discussion). The term V2/2g describes the kinetic energy of the flow (m). The specific energy of the flow H (m) is the sum of the water depth and kinetic energy at a point in the channel where

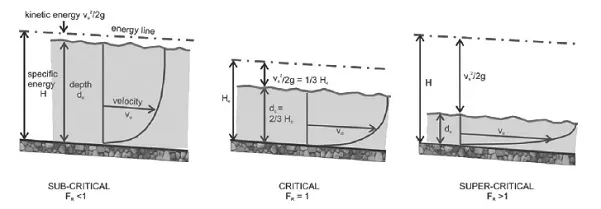

There are only three states of flow based on velocity and depth combinations: (1) subcritical, the depth is two times or more greater than the kinetic energy, typically in deeper pools and mildly sloping channels; (2) critical, the depth is two times the kinetic energy as the water flows over riffle crests, protruding boulders, or in steeply sloping streams; and (3) supercritical, the depth of flow is less than two times the kinetic energy in waterfalls and short vertical drops below boulders and ledges for example.

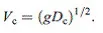

The Froude number Fr, where Fr = V/(gD)1/2 is equal to 1 for critical flow, less than 1 for subcritical flow, and greater than 1 for supercritical flow (Figure 2).

When Fr = 1, the critical velocity is

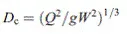

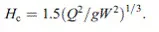

The critical depth Dc and critical specific energy Hc may be expressed in terms of the discharge Q (m3 s–1) and width of the flow W (m):

Figure 2. Three possible states of flow based on velocity and depth combinations for rectangular channels and associated Froude numbers.

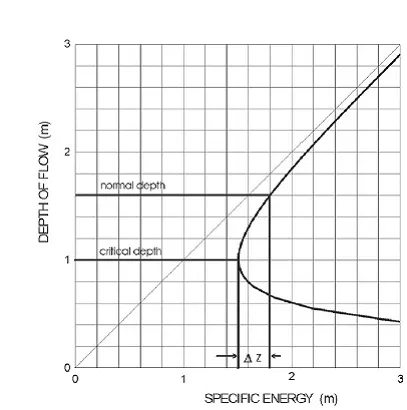

Figure 3. Combinations of depth and velocity that can occur for a given discharge and width are shown in this specific energy diagram. The minimum specific energy occurs at the critical depth. If the resistance-governed normal depth, in this case for a uniform channel with no backwater effects, is greater than the critical depth, there is room for the manipulation of the local channel cross section without changing the flood stage [Chanson, 1994]. In this case, the bed may be raised by the height ΔZ. In some cases, for example, in incised streams, riffle crests may be set much higher to allow normal flood discharges to enter the floodplain.

All combinations of depth and velocity for a given discharge in a channel cross section can be expressed as a specific energy curve where the depth of flow D is plotted against the specific energy H (Figure 3). The point of minimum specific energy required for a given width and discharge occurs at the critical depth (Dc), where the curve reverses slope between the subcritical zone and supercritical zone, in this case at a depth of 1.0 m.

2. LOCAL HYDRAULICS AND HABITAT PREFERENCES

Flows described by the Froude number have been mapped and linked to three traditional stream habitat classifications: riffles, runs, and pools [Jowett, 1993]. Species-specific habitat preferences based on observed combinations of velocity, depth, and substrate (termed habitat suitability indices) are compiled for a wide variety of fish [Bovee, 1982; Keeley and Slaney, 1996]. Four examples of observed habitats and subsequent projects designed to mimic the site-specific channel geometry and hydraulics follow.

2.1. Fish Habitat Preferences: Jumping Pound Creek, Alberta, Canada

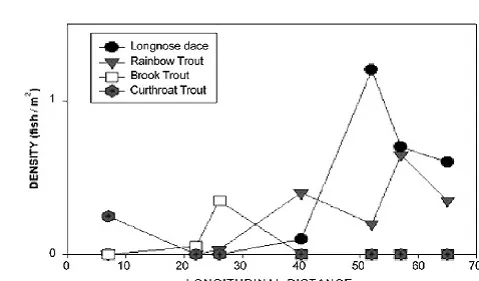

The abundance of fish species was observed to increase with the drainage area and stream width in the upper reaches of Jumping Pound Creek, Alberta, Canada (Figure 4) [Glozier, 1989].

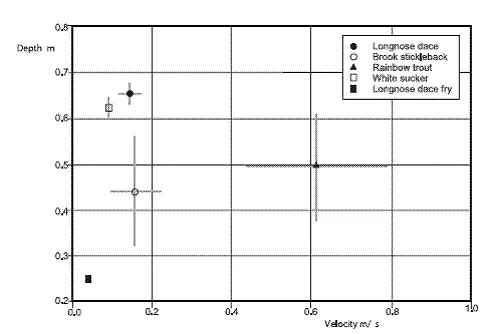

The fish are not distributed uniformly in the sample reaches. The velocity and depth preferences for species in the lower reach (Figure 5) are shown in Figure 6 and Table 1 [Swanson and Ray, 2003].

Figure 4. Increasing number of fish species from the headwaters to near the mouth of Jumping Pound Creek, Alberta, measured in kilometers [Glozier, 1989].

Figure 5. Lower sample reach of Jumping Pound Creek, Alberta.

The Froude number of habitats increases as the smaller species mature from fry to adult. Larger juvenile rainbow trout (47 times fry lengths) were found in higher velocity water with Froude numbers that were 10 times greater than those in the smaller fish locations. Similar observations have been made for cutthroat trout in Chapman Creek, British Columbia, Canada (see example 4 of Bates [2000]).

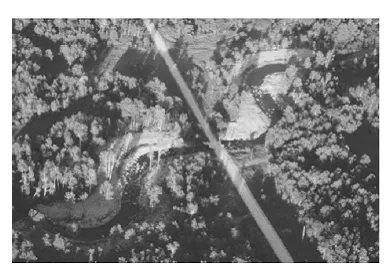

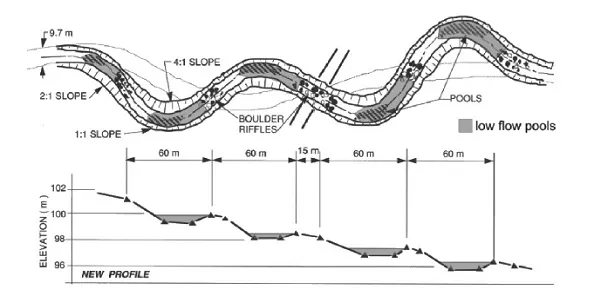

Stream restoration projects for a range of species and life stages can be designed to create a similar diversity of hydraulic conditions by altering the reach hydraulics with pool, riffle, and run profiles. For example, the dimensions of natural meanders with proven adult trout habitats were mimicked in recreating meanders in the North Pine River (Figure 7) [Newbury and Gaboury, 1993]. The project plan and profile are shown in Figure 8. Similar profiles showing equal drops in runs and riffles have been observed in meandering streams [Leopold et al., 1964].

Table 1. Froude Number at Observed Fish Locations in the Lower Reach of Jumping Pound Creek, Alberta, Canada

| Longnose Dace | fry | 0.026 |

| | adult | 0.055 |

| River Shiner | fry | 0.027 |

| | adult | 0.038 |

| Spottail Shiner | fry | 0.026 |

| | adult | 0.037 |

| Brook Stickleback | juvenile | 0.074 |

| White Sucker | juvenile | 0.036 |

| Rainbow Trout | juvenile | 0.276 |

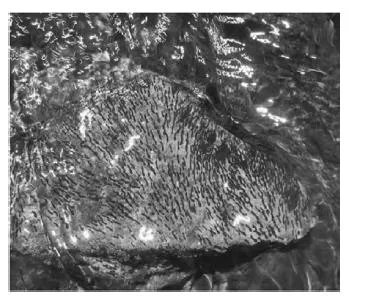

2.2. Benthic Habitats in Critical Flow

The life cycle for many benthic insects requires a period of attachment or occupation on the streambed in an optimum feeding location for grazing surface algae or capturing organic drift [Allan, 1995]. Algae growth occurs where there is maximum light penetration in zones of minimum depth. This occurs in shallow runs and on the surface of large cobbles and boulders in riffles and rapids. Insects in these highvelocity habitats have developed streamlined bodies with low drag coefficients and employ a variety of anchoring strategies, such as hooks, claws, glues, and the attachment of heavier materials to their bodies or external cases. Black-fly larvae holding on to the rock surface with a salivary glue and hooks and Caddisfly larvae in cases made of fine bed materials glued to the rock surface are shown in Figures 9 and Figure 10. Riffles are an important source of food production for fish because of the relatively high macroinvertebrate production relative to other parts of the channel [Allan, 1995].

Figure 6. Depth and velocity measurements at fish locations observed in the lower reach of Jumping Pound Creek, Alberta.

Figure 7. Riffle, runs, and meanders constructed though a straightened highway crossing on the North Pine River, Manitoba, in 1990. The reconstructed meanders mimic natural adult trout habitats found elsewhere in the river. Photo by K. Kansas, Manitoba Fisheries.

Figure 8. Plan and profile of the North Pine River, Manitoba, trout pool project. The still water levels extend halfway around the meander bends observed in other meandering reaches. The spacing and radius of curvature surveyed in nearby unaltered trout pools are the average observed in meandering alluvial rivers [Chang, 1988].

Figure 9. Blackfly larvae in a critical flow zone on the surface of a large cobble, Battle Creek, Saskatchewan.

Stream restoration projects designed to sustain resident fish populations must create local hydraulic conditions in riffles and rapids that are elastic in the sense that the target conditions will persist over a range of discharges as the stream stage changes. This can be accomplished by arranging cobbles and boulders of different sizes and elevations of the surface of riffles and rapids that maintain similar near-emergent conditions over a wide range of depths. Resilient designs that address a range of flow conditions while still meeting project objectives are also more likely to persist into the future under changing hydrology due to climate and land use change. For example, in 1991, emergent boulders and cobbles were added to a uniform bedrock reach of the Whiteshell River MB to create pools and insect habitats in a reach regularly stocked with rainbow trout from an adjacent hatchery (Figure 11). The reach was developed for the Manitoba Fly Fishers Association as a training site for student fishers [Newbury, 2010]. Other than a loss of cover as woody debris decayed, the created habitats have persisted for 17 years (Figure 1...