![]()

1

DOPAMINERGIC HYPOTHESIS OF SCHIZOPHRENIA: A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Aurelija Jucaite and Svante Nyberg

In search of evidence for the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia, this review focuses on studies of patients with schizophrenia. The review is composed of two parts: the first serves as a short reminder of the anatomy and function of the dopamine system, and the second guides the reader through the history of scientific discoveries and paradigms used to investigate the role of dopamine in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.

1.1 DOPAMINE SYSTEM: NEUROANATOMY AND MODE OF ACTIVITY

Dopamine is a phylogenetically old neurotransmitter intrinsic to brain function and behavior. It is of central importance in movement, reward-associated behavior, and emotions. Abnormal patterns of dopamine neurotransmission have been suggested to underlie several neurological and psychiatric disorders, for example, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases, schizophrenia, drug abuse, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

1.1.1 Macroanatomy

Dopamine is synthesized in dopaminergic neurons from the amino acid tyrosine by the enzymes tyrosine hydroxylase (forming L-3,4-dihydroxylphenylalanine [L-DOPA]) and L-amino acid decarboxylase (AACD). Tyrosine hydroxylase is a rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of dopamine, and its mRNA expression is abundant in human mesencephalon.

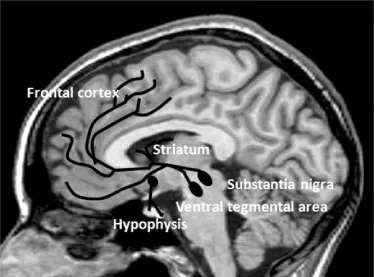

Dopaminergic neurons showing the highest expression of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA are aggregated in distinct clusters: the ventral midbrain (A8-9-10), diencephalon (A11-15), and telencephalon (A16-olfactory bulb, A17, and the retina). Dopaminergic neurons cluster into the three major nuclei in the brain that contain cell bodies: (1) the substantia nigra pars compacta (SN, A9), located in the ventral midbrain; (2) the ventral tegmental area (VTA) or A10, lying medial to SN; and (3) the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus, throughout the posterior and dorsomedial nuclei of hypothalamus (A11–15, in the diencephalon) [1, 2]. Smaller groups of dopaminergic neurons are located in the retina and the olfactory bulb, in the human cerebral cortex [3, 4], in the subcortical white matter, and in the striatum [5, 6].

The dopaminergic projections from these neurons are distributed throughout the anatomically segregated neuronal systems that control motor, limbic, and cognitive aspects of behavior (Fig. 1.1). The dopaminergic projections form three major long pathways:

1. The nigrostriatal pathway contains over 80% of all dopaminergic innervation, primarily targeting the striatal medium spiny projection neurons. Dopamine modulates cortical innervation to the striatum and is involved in the control of movement.

2. The mesolimbic pathway, with neurons from VTA synapsing in the nucleus accumbens and amygdala, is engaged in emotions, motivation, goal-directed behavior, pleasurable sensations, the euphoria of drug abuse, and the delusions and hallucinations of psychosis [7].

3. The mesocortical pathway originates in the VTA and terminates in the forebrain with its most abundant innervation in the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate, insula, entorhinal cortices. The majority of target neurons are excitatory pyramidal cells and minor target group are dendrites of local inhibitory neurons [8, 9] largely involved in cognitive functions.

There is a topographic organization of the SN/VTA innervation to the cortical regions (e.g., dorsal prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices receive innervation from the dorsal group of cells of the SN and the retrobulbar area), while ventromedial limbic cortices receive input from the VTA [10]. In addition, several shorter pathways distinct from the major projections have been identified: the tubero-infundibular pathway, which projects from the hypothalamic nucleus to the anterior pituitary and contributes to the neurohumoral regulation of lactation; the mesohippocampal tract, which originates in the SN/VTA and terminates at the hippocampus and is involved in memory formation; and the mesofrontal tract, which traverses from the SN to the prefrontal cortex and is active in reward mechanisms. Ultrashort dopaminergic pathways connecting inner and outer layers of the retina (interplexiform amacrine-like neurons) and cells in the olfactory bulb (periglomerular dopamine cells) have also been reported [11], although their function is less well understood.

1.1.2 Microanatomy

Neurotransmission, including the synthesis–storage–release–receptor binding of the monoamine neurotransmitter as well as its uptake or degradation, is a highly controlled process. The complex balance of this cascade determines the intensity of dopaminergic signaling.

In 1979, Kebabian and Calne [12] found that dopamine exerts its effects by binding to two classes of receptors, dubbed as the dopamine D1 and D2 receptors (D1R and D2R). These receptors could be differentiated pharmacologically, biologically, physiologically, and by their anatomical distribution. All dopamine receptors are G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Heteromeric guanine nucleotide-binding proteins (G-proteins) are made up of alpha (α), beta (β), and gamma (γ) subunits, binding to which will influence effector recognition and can activate different signaling cascades. Therefore, based on the receptor coupling to GPCRs, activated subunits of G-proteins and further effects on second messengers, dopamine receptors are presently subdivided into the Gs-, Gq-, or Golf-coupled D1 receptor family and Gi/o D2 receptor family [13]. By their different G-protein coupling, D1-family and D2-family receptors have opposing effects on adenylyl cyclase activity (i.e., stimulatory vs. inhibitory effect, respectively), on cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) concentration, as well as on phosphorylation processes [14]. Gene cloning revealed that DR2 family is further subdivided into dopamine D2, D3, and D4 receptors (D2R, D3R, D4R) and their splice forms. A short splice version of D2 (D2Sh) and a long splice version of D2 (D2Lh) coexist in the brain as the most characterized dopamine receptor splice variants. The D2Sh are predominantly presynaptic receptors (autoreceptors) and participate in the feedback mechanisms, or, when situated on the terminals, affect synthesis, storage, and release of dopamine into the synaptic cleft. The D2Lh are viewed as the classical postsynaptic receptors. The D1R family includes dopamine D1 and D5 receptors (D1R, D5R).

1.1.2.1 Dopamine D2/D3/D4 Receptors in the Human Brain (D2-like receptors)

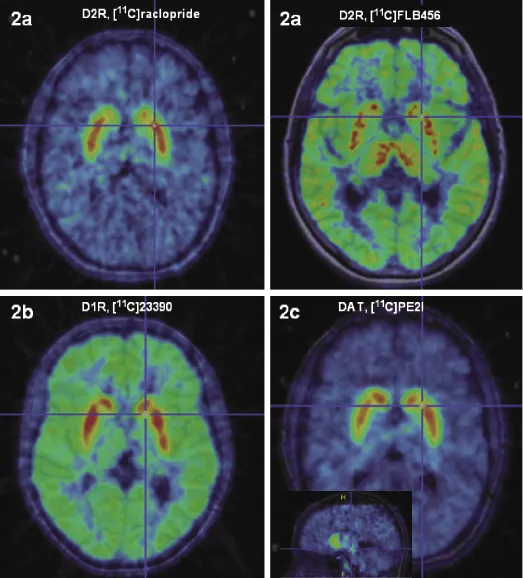

The precise anatomical location of the dopamine receptors in the human brain has been most fully established for the dopamine D2 receptors. In the adult human brain, D2R mRNA is markedly expressed in the striatum, neocortex, hippocampus, and amygdaloid complex, and differential expression is found in the thalamus as well as in most of the hypothalamic nuclei [15, 16]. D2R expression also follows a regional density pattern; there is a density gradient of D2R in decreasing order from the striatal structures, to the thalamus, to the midbrain, and finally, to the neocortex [17–19]. The dopamine D2R distribution in the neocortex is low, uneven, and varies between higher values in the temporal lobes (including hippocampus and amygdala) to minute receptor densities in the occipital lobes [20, 21]. Very heterogeneous D2R density is also found in the thalamus and in the striatum [22]. (Fig. 1.2a shows D2/D3R distribution as measured by molecular imaging in humans in vivo)

The D3R has a different anatomical distribution, being absent in the dorsal striatum, but abundant in the ventral striatum, thalamus, and hypothalamic nuclei (mainly mammillary bodies) and at low levels in the striatum and throughout the cortex. This is consistent with the mRNA expression pattern [19, 23]. However, so far there are no selective agonists available for D3Rs, and they are indistinguishable from D2Rs in in vivo measurements.

The D4R has eight polymorphic variants in humans [24]. The receptor is found at a high density in the limbic cortex and in the hippocampus and is absent from the motor regions of the brain. mRNA for D4R has low expression in human cortex and striatum [25]. D4Rs are preferentially co-expressed with enkephalin in GABAergic neurons, thus predominantly modulating inhibitory control in the cortex and projection pathways [26]. No compounds are yet available for in vivo visualization of D4R, nor are there any pharmacological tools to distinguish between the physiological or functional contributions of D4 and D2/D3 receptors.

1.1.2.2 Dopamine D1/D5 Receptors in the Human Brain (D1-like receptors)

The cells expressing D1R mRNA are localized in the striatum, cerebral cortex, and bed nucleus of stria terminalis [16]. Dopamine D1R mRNA expression in the human cerebral cortex is the most abundant of all dopamine receptors. It is distributed in a laminar pattern and differs quantitatively between the cortical regions and subregions, with the highest expression in the medial orbital, insular, and parietal cortices [27]. Extremely low levels of D1R mRNA are found in the hippocampus, diencephalon, brainstem, and cerebellum, suggesting that neurons in those areas can mediate dopamine transmission via D1R, although mainly it would be mediated via D2/D3Rs. In the normal adult human brain, D1Rs show a widespread neocortical distribution, with D1R predominantly localized on spines and shafts of projection neurons [28]. D1Rs are found in high density in the basal ganglia, including regions of the caudate, putamen, globus pallidus, and SN [18, 29]. (D1R binding distribution in vivo is depicted in Fig. 1.2b). D1Rs in the globus pallidus and the SN are most likely localized on terminals, as there are no D1R mRNA expresssing cells in those regions. Within the basal ganglia, D1Rs are most abundant on GABAergic neurons expressing dynorphin/substance P [30].

D5R mRNA has predominant cortical expression and scattered low expression of mRNA is found in the subcortical structures, striatum, thalamus, and claustrum [31]. No radioligand selective for D5R is available. Immunochemistry studies suggest that D5Rs are concentrated in the hippocampus and entorrhinal cortex, but are also found in the thalamus and in the striatum [32].

The major functions of dopamine receptors are the recognition of the specific transmitter dopamine and the subsequent activation of effectors, leading to altered cell membrane potential and changes in the biochemical state of the postsynaptic cell. Neurotransmission via dopamine receptors is not sufficient to generate action potentials. Investigations into a possible neuromodulatory role of dopamine from the 1970s onward (i.e., electrophysiological experimental studies and microiontophoresis in vivo) have demonstrated that dopamine moderately depolarizes or hyperpolarizes neurons, usually by 5–7 mV [33]. Thus, dopamine acts as a neuromodulator, potentiating or attenuating cellular responses evoked by other neurotransmitters and thereby modulating neurotransmitter release, electrical excitability, and the neural firing properties of the target cell.

1.1.2.3 Regulation of Dopamine Neurotransmission (Synthesis, Reuptake, Storage, Degradation)

Dopamine levels in the synaptic/extrasynaptic environment are controlled by a number of molecular mechanisms: dopamine reuptake involving the presynaptic dopamine transporter, storage by vesicular monoamine transporters, and metabolic degradation by the enzymes catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT) and monoamine oxidase (MAO).

Dopamine Transporter (DAT)

The topology of DAT shows that it is a plasma membrane protein, with 12 transmembrane domains. It is localized only on dopaminergic neurons and is considered the phenotypic marker of dopaminergic neur...