eBook - ePub

Nanomaterials in Catalysis

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Nanomaterials in Catalysis

About this book

Nanocatalysis has emerged as a field at the interface between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis and offers unique solutions to

the demanding requirements for catalyst improvement. Heterogeneous catalysis represents one of the oldest commercial applications of nanoscience and nanoparticles of metals, semiconductors, oxides, and other compounds have been widely used for important chemical reactions. The main focus of this fi eld is the development of well-defined catalysts, which may include both metal nanoparticles and a nanomaterial as the support. These nanocatalysts should display the benefits of both homogenous and heterogeneous catalysts, such as high efficiency and selectivity, stability and easy recovery/recycling. The concept of nanocatalysis is outlined in this book and, in particular, it provides a comprehensive overview of the science of colloidal nanoparticles. A broad range of topics, from the fundamentals to applications in catalysis, are covered, without excluding micelles, nanoparticles in ionic liquids, dendrimers, nanotubes, and nanooxides, as well as modeling, and the characterization of nanocatalysts, making it an indispensable reference for both researchers at universities and

professionals in industry.

the demanding requirements for catalyst improvement. Heterogeneous catalysis represents one of the oldest commercial applications of nanoscience and nanoparticles of metals, semiconductors, oxides, and other compounds have been widely used for important chemical reactions. The main focus of this fi eld is the development of well-defined catalysts, which may include both metal nanoparticles and a nanomaterial as the support. These nanocatalysts should display the benefits of both homogenous and heterogeneous catalysts, such as high efficiency and selectivity, stability and easy recovery/recycling. The concept of nanocatalysis is outlined in this book and, in particular, it provides a comprehensive overview of the science of colloidal nanoparticles. A broad range of topics, from the fundamentals to applications in catalysis, are covered, without excluding micelles, nanoparticles in ionic liquids, dendrimers, nanotubes, and nanooxides, as well as modeling, and the characterization of nanocatalysts, making it an indispensable reference for both researchers at universities and

professionals in industry.

Information

Chapter 1

Concepts in Nanocatalysis

1.1 Introduction

Catalysis occupies an important place in chemistry, where it develops in three directions, which still present very few overlaps: heterogeneous, homogeneous and enzymatic. Thus, homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis are well-known as being two different domains defended by two scientific communities (molecular chemistry and solid state), although both are looking for the same objective, the discovery of better catalytic performance. This difference between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis is mainly due to the materials used as catalysts (molecular complexes in solution versus solid particles, often grafted onto a support), as well as to the catalytic reaction conditions applied (for example liquid-phase reactions versus gas-phase ones). Considering the advantages of these two catalytic approaches, on the one hand heterogeneous catalysts are easy to recover but present some drawbacks, such as the drastic conditions they require to be efficient and the mass transport problems; on the other hand, homogeneous catalysts are known for their higher activity and selectivity, but the separation of expensive transition metal catalysts from substrates and products remains a key issue for industrial applications [1]. The first attempts to bridge the gap between these two communities date from the 1970s to the early 1980s. From one side chemists working in the molecular field, such as J.M. Basset, M. Che, B.C. Gates, Y. Iwasawa and R. Ugo, among others, initiated pioneering works on surface molecular chemistry to develop single-site catalysts, and/or reach a better understanding of conventional supported catalyst preparation through a molecular approach; from the other side, chemists of the solid state, such as G. Ertl and G. Somorjai, were interested in the molecular understanding of surface chemical catalytic processes. For the latter, the revolutionary development of surface science at the molecular level was possible thanks to the development of techniques of preparation of clean single crystal surfaces and characterization of structure and chemical composition under ultrahigh vacuum [(X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), atomic emission spectroscopy (AES), low energy electron diffraction (LEED) etc]. Once again, although these scientists aimed at a common objective, little interaction or cross-fertilization action has appeared during the last 20 years. One should however cite the first International Symposium on Relations between Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalysis, organized on Prof. Delmon's initiative in Brussels (Belgium) in 1973. Interestingly, this event appeared 17 years after the first International Congress on Catalysis (Philadelphia, 1956) and 5 years before the first International Symposium on Homogeneous Catalysis (Corpus Christi, 1978). In parallel, although colloidal metals of Group 8 were among the first catalysts employed in the hydrogenation of organic compounds, the advent of high pressure hydrogenation and the development of supported and skeletal catalysts meant that colloidal catalysis has hardly been explored for many years [2–4].

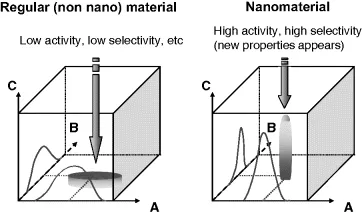

Since the end of the 1990s, and with the development of nanosciences, nanocatalysis has clearly emerged as a domain at the interface between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis, which offer unique solutions to answer the demanding conditions for catalyst improvement [5, 6]. The main focus is to develop well-defined catalysts, which may include both metal nanoparticles and a nanomaterial as support. These nanocatalysts should be able to display the ensuing benefits of both homogenous and heterogeneous catalysts, namely high efficiency and selectivity, stability and easy recovery/recycling. Specific reactivity can be anticipated due to the nanodimension that can afford specific properties which cannot be achieved with regular, non-nano materials (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Nanoarchitecture: an avenue to superior precision. Axes are: A: composition of functional sites; B: ordering level of sites; C: functional properties of material.

In this approach, the environmental problems are also considered. Definitions can be given: the term ‘colloids’ is generally used for nanoparticles (NPs) in liquid-phase catalysis, giving rise to ‘colloidal catalysis,’ while ‘nanoparticle’ is more often attributed to NPs in the solid state, thus related to the heterogeneous catalysis domain. The terms ‘nanostructured’ or ‘nanoscale’ materials (and by extension ‘nanomaterials’) are any solid that has a nanometer dimension. Despite these differences in nomenclature, NPs are always implicated and ‘nanocatalysts’ or ‘nanocatalysis’ summarize well all the different cases.

In the nanoscale regime, neither quantum chemistry nor the classical laws of physics hold. In materials where strong chemical bonding is present, delocalization of electrons can be extensive, and the extent of delocalization can vary with the size of the system. This effect, coupled with structural changes, can lead to different chemical and physical properties, depending on size. As for other properties, surface reactivity of nanoscale particles is thus highly size-dependent. Of particular importance for chemistry, surface energies and surface morphologies are also size-dependent, and this can translate to enhanced intrinsic surface reactivity. Added to this are large surface areas for nanocrystalline powders and this can also affect their chemistry in substantial ways [7]. Size reduction to the nanometer scale thus leads to particular intrinsic properties (quantum size effect) for the materials that render them very promising candidates for various applications, including catalysis. Such interest is well established in heterogeneous catalysis, but colloids are currently experiencing renewed interest to get well-defined nanocatalysts to increase selectivity.

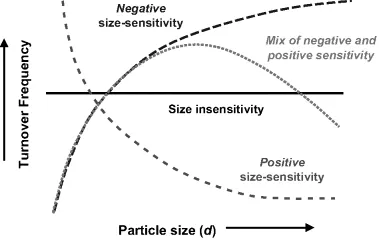

Much work in the field has focused on the elucidation of the effects of nanoparticle size on catalytic behavior. As early as 1966, Boudart asked fundamental questions about the underlying relationship between particle size and catalysis, such as how catalyst activity is affected by size in the regime between atoms and bulk, whether some minimum bulk-like lattice is required for normal catalytic behavior, and whether an intermediate ideal size exists for which catalytic activity is maximized [8]. Somorjai's group has studied this issue extensively. Although there is tremendous variation in the relationships between size and activity depending on the choice of catalyst and choice of reaction, these relationships are often broken into three primary groups: positive size-sensitivity reactions, negative size-sensitivity reactions, and size-insensitive reactions. There is also a fourth category composed of reactions for which a local minima or maxima in activity exists at a particular NP size (see Figure 1.2) [9, 10]. Positive size-sensitivity reactions are those for which turnover frequency increases with decreasing particle size. The prototypical reaction demonstrating positive size-sensitivity is methane activation. Dissociative bond cleavage via σ-bond activation as the rate-limiting step is a common feature in reactions with positive size-sensitivity. Negative size-sensitivity reactions are those for which turnover frequency decreases with decreasing particle size. In this case, formation or dissociation of a π-bond is often the rate-limiting step. The prototypical reactions for this group are dissociation of CO and N2 molecules, which each require step-edge sites and contact with multiple atoms. These sites do not always exist on very small NPs, in which step-edges approximate adatom sites. These reactions also sometimes fall into the fourth category of those with a local maximum in turnover frequency versus particle size because certain particle sizes geometrically favor the formation of these sorts of sites. The third type of reaction is the size-insensitive reaction, for which there is no significant dependence of turnover frequency on nanoparticle diameter. The prototypical size-insensitive reaction is hydrocarbon hydrogenation on transition metal catalysts, for which the rate-limiting step is complementary associative σ-bond formation. Although these effects are often referred to as structure-sensitivity effects, they are referred to as size-sensitivity effects here in order to further distinguish them from another type of structure-sensitivity, which is derived from differences in crystal face and which is discussed below.

Figure 1.2 Major classes of size-sensitivity, which describe the relationships between NP size and turnover frequency for a given combination of reaction and NP catalyst. (------) negative size-sensitivity; (- - - -) positive size-sensitivity; (·······) Mix of negative and positive sensitivity.

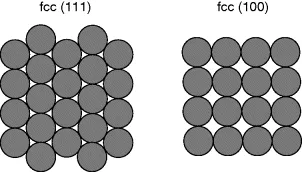

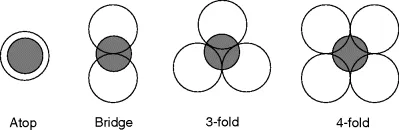

Aside from considerations of NP size, a second major area of inquiry is that of the effect of nanoparticle shape on reaction rate, selectivity, and deactivation. This work is derived from the abundance of research done on single crystal surfaces, which has demonstrated what is known as structure sensitivity in catalysis. Experiments on a wide variety of catalysts have determined that the atomic arrangement of atoms on a surface has a significant effect on catalyst behavior. As demonstrated in Figures 1.3 and 1.4, the type of crystal face dramatically affects the coordination, number of nearest neighbors, and both two- and three-dimensional geometry of the catalytically active surface atoms. The availability of particular types of adsorption sites can have a large effect on catalysis, as it is common for adsorbates to differ in their affinity for each type of adsorption site. Consequently, the presence or absence of a particular type of site can affect not only reaction rates, but also selectivity. However, not all reactions are structure sensitive and some reactions are known to be structure sensitive only within a range of specific conditions. In the case of nanoparticle catalysts, structure-sensitivity is manifested in terms of NP shape. When little attention is given to shape, most NPs adopt roughly spherical shapes, often referred to as polyhedra or octahedra, in order to minimize surface energy.

Figure 1.3 Two of the most common fcc crystal faces, (111) (left) and (100) (right).

Figure 1.4 Four of the most common adsorption sites found on single crystal terraces.

These NPs predominately feature (111)-oriented surface atoms, which is the lowest energy...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Foreword

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- Chapter 1: Concepts in Nanocatalysis

- Chapter 2: Metallic Nanoparticles in Neat Water for Catalytic Applications

- Chapter 3: Catalysis by Dendrimer-Stabilized and Dendrimer-Encapsulated Late-Transition-Metal Nanoparticles

- Chapter 4: Nanostructured Metal Particles for Catalysts and Energy-Related Materials

- Chapter 5: Metallic Nanoparticles in Ionic Liquids – Applications in Catalysis

- Chapter 6: Supported Ionic Liquid Thin Film Technology

- Chapter 7: Nanostructured Materials Synthesis in Supercritical Fluids for Catalysis Applications

- Chapter 8: Recovery of Metallic Nanoparticles

- Chapter 9: Carbon Nanotubes and Related Carbonaceous Structures

- Chapter 10: Nano-oxides

- Chapter 11: Confinement Effects in Nanosupports

- Chapter 12: In Silico Nanocatalysis with Transition Metal Particles: Where Are We Now?

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Nanomaterials in Catalysis by Philippe Serp, Karine Philippot, Philippe Serp,Karine Philippot in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Industrial & Technical Chemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.