![]()

Chapter 1

Principles of Brain Function and Structure: 1 Genetics, Physiology and Chemistry

1.1 Introduction

It has become fashionable periodically to ascribe much psychopathology to the evils of modern society, and the resurgence of this notion from time to time reflects the popularity of the simple. Often imbued with political overtones, and rarely aspiring to scientific insights, such a view of the pathogenesis of psychiatric illness ignores the long tradition of both the recognition of patterns of psychopathology and successful treatment by somatic therapies. Further, it does not take into account the obvious fact that humanity's biological heritage extends back many millions of years.

In this and the next chapter, consideration is given to those aspects of the neuroanatomy and neurochemistry of the brain that are important to those studying biological psychiatry. Most emphasis is given to the limbic system and closely connected structures, since the understanding of these regions of the brain has been of fundamental importance in the development of biological psychiatry. Not only has a neurological underpinning for ‘emotional disorders’ been established, but much research at the present time relates to the exploration of limbic system function and dysfunction in psychopathology.

1.2 Genetics

Every cell in the human body contains the nuclear material needed to make any other cell. However, cells differentiate into a specific cell by expressing only partially the full genetic information for that individual. While it is beyond the scope of this book to fully explain all of modern genetics, it is important to grasp several basic aspects that are involved in building and maintaining the nervous system, and which may impact on psychiatric diseases.

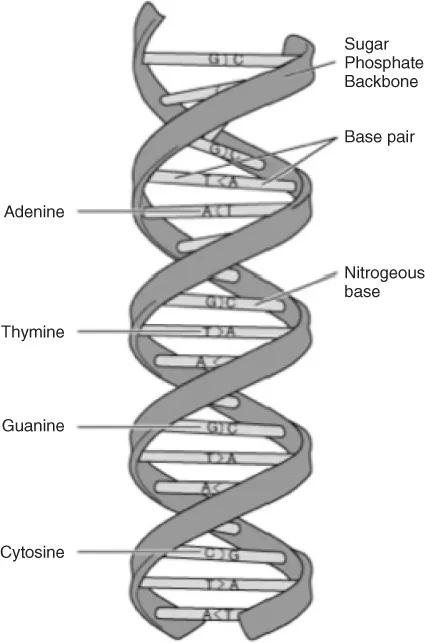

Modern genetic theories are based on knowledge of the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) molecule, its spontaneous and random mutations and the recombination of its segments. DNA is composed of two intertwined strands (the double helix) of sugar-phosphate chains held together by covalent bonds linked to each other by hydrogen bonds between pairs of bases. There is always complementary pairing between the bases, such that the guanine (G) pairs with cytosine (C), and the adenine (A) with thymine (T). This pairing is the basis of replication, and each strand of the DNA molecule thus forms the template for the generation of another. Mammalian DNA is supercoiled around proteins called histones (Figure 1.1). Recently it has been discovered that histones can be modified by life experiences. The actual protein folding of the genetic materials changes as a function of histones or methylation on the DNA. Early life experiences can actually cause large strands of the DNA to become silent and not expressed (McGowan et al., 2008; Parent and Meaney, 2008).

On the DNA strand are many specific base sequences that encode for protein construction. Thus, proteins are chains of amino acids, and one amino acid is coded by a triplet sequence of bases (the codon). For example, the codon TTC codes for phenylalanine.

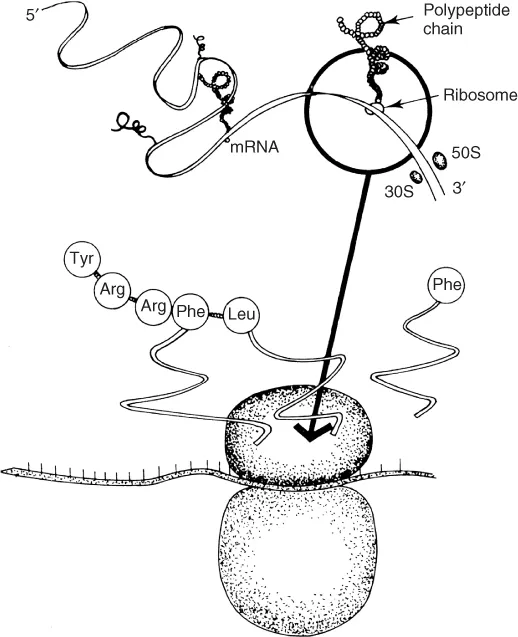

DNA separates its double helix in a reaction catalysed by DNA polymerase. In the synthesis of protein, ribonucleic acid (RNA) is an intermediary. RNA is almost identical to DNA, except that uracil (U) replaces thymine, the sugar is ribose, and it is single-stranded. Thus, an RNA molecule is created with a complementary base sequence to the DNA, referred to as messenger RNA (mRNA). This enters the cytoplasm, attaches to ribosomes, and serves as a template for protein synthesis. Transfer RNA (tRNA) attaches the amino acids to mRNA, lining up the amino acids one at a time to form the protein. The tRNA achieves this by having an anticodon at one end attach to the mRNA and the amino acid at the other (see Figure 1.2). Coding occurs between the start and stop codons.

Much is now known regarding the various sequences of bases that form the genetic code. In total, chromosomal DNA in the human genome has approximately 3 billion base pairs. There are 20 amino acids that are universal constituents of proteins, and there are 64 ways of ordering the bases into codons (Wolpert, 1984). Most amino acids are represented by more than one triplet, and there are special techniques for starting and stopping the code. Although it was thought that the only direction of information flow was from DNA to RNA to protein, investigations of tumour cells have revealed retroviruses: RNA viruses that can be incorporated into host DNA.

The genetic programme is determined by DNA, and at various times in development, and in daily life, various genes will be turned on or off depending on the requirements of the organism. There is a constant interplay between the genetic apparatus and chemical constituents of the cell cytoplasm.

In the human cell there is one DNA molecule for each chromosome, and there are some 100 000 genes on 46 chromosomes. This constitutes only a small portion of the total genomic DNA, and more than 90% of the genome seems non-coding. About 50% of human DNA consists of short repetitive sequences that either encode small high-abundance proteins such as histones, or are not transcribed. A lot of these are repetitive sequences dispersed throughout the genome, or arranged as regions of tandem repeats, referred to as satellite DNA. Such repeats are highly variable between individuals, but are inherited in a Mendelian fashion. These variations produce informative markers, and when they occur close to genes of interest are used in linkage analysis. Complimentary cDNA probes are produced using mRNA as a template along with the enzyme reverse transcriptase. The latter is present in RNA viruses; HIV is a well-known example. Reverse transcriptase permits these viruses to synthesize DNA from an RNA template. It is estimated that 30–50% of the human genome is expressed mainly in the brain.

Retroviruses enter host cells through interaction at the host cell surface, there being a specific receptor on the surface. Synthesis of viral DNA then occurs within the cytoplasm, the RNA being transcripted into DNA by reverse transcriptase, and the viral DNA becoming incorporated into the host's genome.

Oncogenes are DNA sequences homologous to oncogenic nucleic acid sequences of mammalian retroviruses.

In the human cell the chromosomes are divided into 22 pairs of autosomes, plus the sex chromosomes: XX for females and XY for males. Individual genes have their own positions on chromosomes, and due to genetic variation different forms of a gene (alleles) may exist at a given locus. The genotype reflects the genetic endowment; the phenotype is the appearance and characteristics of the organism at any particular stage of development. If an individual has two identical genes at the same locus, one from each parent, this is referred to as being a homozygote; if they differ, a heterozygote. If a heterozygote develops traits as a homozygote then the trait is called dominant. There are many diseases that are dominantly inherited. If the traits are recessive then they will only be expressed if the gene is inherited from both parents. Dominant traits with complete penetrance do not skip a generation, appearing in all offspring with the genotype.

If two heterozygotes for the same recessive gene combine, approximately one in four of any children will be affected; two will be carriers, and one unaffected. When there is a defective gene on the X chromosome, males are most severely affected, male-to-male transmission never occurs, but all female offspring of the affected male inherit the abnormal gene.

Many conditions seem to have a genetic component to their expression, but do not have these classic (Mendelian) modes of inheritance. In such cases polygenetic inheritance is suggested.

Mitochondrial chromosomes have been identified. They are densely packed with no introns and they represent around 1% of total cellular DNA. They are exclusively maternally transmitted. Unlike nuclear chromosomes, present normally in two copies per cell at the most, there are thousands of copies of the mitochrondrial chromosomes per cell.

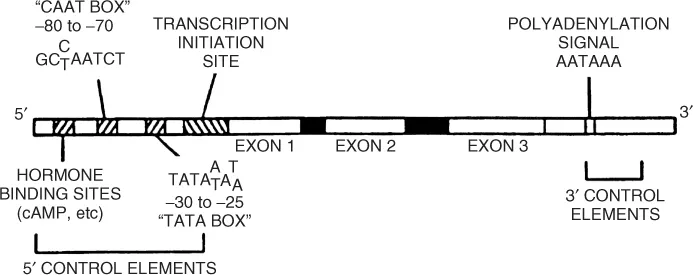

In the gene there are coding sequences, called exons, and intervening non-coding segments referred to as introns. Some sequences occur around a gene, regulating its function. It is not unusual for the genes of even small proteins to be encoded in many small exons (under 200 bases) spread over the chromosome. Most genes have at least 1200 base pairs, but are longer because of introns. Further, important sequences precede the initiation site (or 59), and the end of the gene (39). A model of a generic gene is shown in Figure 1.3. The promotor region is at the 59 end, containing promotor elements and perhaps hormone binding sites. These activate or inhibit gene transcription. The coding region consists of sequences that will either appear in the mature mRNA (exons) or be deleted (introns).

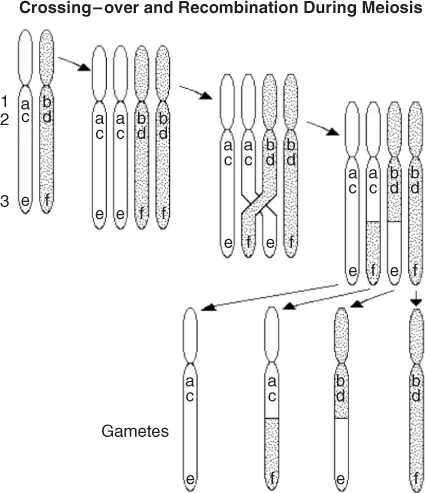

During meiosis, the strands from the two chromosomes become reattached to each other, but each chromosome carries a different allele. There is then a new combination of alleles in the next generation, this exchange being referred to as recombination. The frequency of a recombination between two loci is a function of the distance between them: the closer they are, the less is the likelihood that a recombination will occur between them (Figure 1.4).

Linkage analysis places the location of a particular gene on a chromosome; physical mapping defines the linear order among a series of loci. Genetic distance is measured in centimorgans, reflecting the amount of recombination of traits determined by g...