![]()

1

Overview: Disorders of Menstruation

Paul B. Marshburn and Bradley S. Hurst

Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, North Carolina, USA

Introduction

This book is dedicated to the concept that menstrual cycle events are a vital sign for women. Irregularity in the pattern and amount of vaginal bleeding of uterine origin are often a sign of pathology or an aberration in the function of the hypothalamic, pituitary, and ovarian axis. Clues to disease states are afforded by changes in symptoms related to timing during the menstrual cycle. The process of menstruation may be accompanied by distressing symptoms such as menorrhagia (excessive menstrual blood loss), dysmenorrhea (painful periods), or oligo-amenorrhea (infrequent or absent periods). When the menstrual vital sign is appropriately and methodically interpreted, it can provide a window into the diagnosis of conditions that might be life-threatening or herald systemic disorders that only secondarily impact menstrual function.

In the logical approach to disorders of menstruation, the astute clinician should employ the precepts of Bayes theorem. The medical application of this theorem is summarized by stating that the probability of diagnosing a clinical disorder depends upon evaluating historical and diagnostic information in the population at risk. It is obvious that the interpretation of cyclic menses in a 5-year-old girl is different from that of the cyclic pattern of vaginal bleeding in a woman of reproductive age. For this reason, we have organized this book to discuss disorders of menstruation in the chronologic order of the seasons of a woman’s life. Therefore, sequential chapters begin with discussing abnormal vaginal bleeding in female infants and girls, followed by bleeding in peripubertal adolescents, women of reproductive age, those in the menopausal transition, and finally postmenopausal women. The likelihood of making an accurate diagnosis or achieving successful treatment is therefore dependent upon applying approaches in the appropriate age group and clinical setting, and in the population at risk.

This book is written for any practicing clinician who provides healthcare for girls and women. The authors have attempted to apply their knowledge to provide a conceptual framework to understand the mechanisms responsible for abnormal menstrual bleeding or early pregnancy failure. The exhaustive, academic presentation, however, is substituted for the direct and sensible approaches of expert authors who have a wealth of successful clinical experience based upon the rigorous evaluation of clinical trials. This clinically focused book is aimed at providing gynecologists in practice or in training with a guide for use “in the office” or “at the bedside.” Our emphasis is upon providing an accurate diagnostic algorithm that leads to evidence-based therapy with approaches that are practical, efficient, and cost-effective.

Physiology of Menstruation

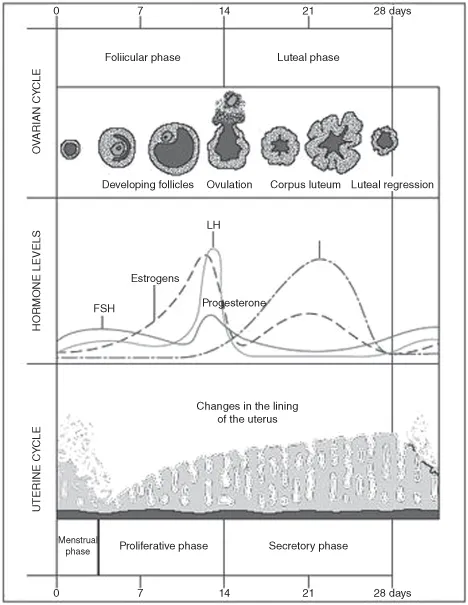

The functional development of the endometrium is orchestrated by ovarian estrogen stimulation during the follicular phase, followed by the postovulatory influence of estrogen and progesterone from the corpus luteum to induce secretory endometrial transformation. This process is crucial for the perpetuation of the human species by inducing proper endometrial development for embryo implantation (Figure 1.1). In the absence of embryo implantation, the endometrium is sloughed during menstruation or “the period,” appropriately termed because it implies a beginning, a middle, and an end. Such a period occurs as a result of physiologic endometrial changes prompted by a decline in steroid production by the corpus luteum if pregnancy is not established. Regular, monthly, menstrual bleeding is the outward manifestation of the ovarian cycle that results from ovulation.

The landmark work of J. E. Markee, published in 1940, has been critical to the understanding of physiologic changes in primate endometrium during the menstrual cycle. Markee transplanted endometrium into an in-vivo observation chamber, the anterior chamber of the eye in rhesus monkeys. In this way, he directly observed endometrial changes during all the phases of the menstrual cycle in experiments that spanned 9 years of work. The cumulative studies of Markee and other investigators indicate that the process of menstruation is a series of universal endometrial events. Further investigation showed that the physiologic processes that start menstruation are also responsible for stopping it.

Paracrine factors, induced by the simultaneous decline in estradiol and progesterone, promote rhythmic contraction of the endometrial spiral arterioles. The resultant endometrial ischemia causes destabilization of the lysosomes, which release prostaglandins (primarily PGF2-alpha) that promote myometrial contractions. Fluid from the ischemic, liquefactive necrosis of endometrial tissue and blood is expelled by these myometrial contractions. Menstrual bleeding decreases after hemostasis from a combination of myometrial contractions and platelet plugging on exposed arteriolar type 2 collagen. The cessation of menstrual flow is completed with the initiation of endometrial tissue repair, growth, and angiogenesis that is required for preparation for implantation in the next cycle. Thus, a period of menstrual bleeding occurs through a process that is initiated by physiologic events that leads to its own conclusion.

Menstrual Parameters

The menstrual cycle may be defined by its length, regularity, frequency, and pattern of menstrual blood loss. The average menstrual cycle length in the reproductive years is between 28 and 30 days, with an average period of menstruation of 4 days, and a volume of blood loss of approximately 30 mL. The primitive woman had fewer menstrual periods because the absence of contraceptive options meant that women were more often pregnant or lactating. Today, women experience approximately 400 menstrual cycles. It has been postulated that the development of hormonal contraception, methods of permanent sterilization, fewer pregnancies per woman, reduced intervals of lactational amenorrhea, and later age at time of first conception have all contributed to an increase in the number of menstrual cycles and the magnitude of menstrual disorders. Heavy menstrual and intermenstrual bleeding is the most common indication for hysterectomy and accounts for 4% of physician consultations annually.

“Abnormal uterine bleeding” is a term applied to deviations from the normal menstrual parameters defined above. The terminology used to describe “abnormal” menstruation, however, has not been defined in a universally accepted manner. The main causes of abnormal uterine bleeding are listed in Table 1.1. Benign disorders of the uterus may present with the complaint of excessive menstrual blood loss and/or an associated irregularity in the pattern of menstrual bleeding. Such benign disorders include endometrial polyps, fibroids, and adenomyosis. However, the vast majority of women complaining of excessive menstrual blood loss have normal endometrium.

Table 1.1 The main recognized causes of abnormal uterine bleeding

Pelvic pathology

Uterine leiomyomas

Uterine adenomyomas or diffuse adenomyosis

Endometrial polyps

Endometrial hyperplasia

Endometrial adenocarcinoma, rare sarcomas

Uterine or cervical infection

Endometrial or cervical infections

Benign cervical disease

Cervical squamous and adenocarcinoma

Myometrial hypertrophy

Uterine arteriovenous malformations (complications of unrecognized early pregnancy)

Systemic disease

Disorders of hemostasis (typically von Willebrand disease and platelet disorders, excessive anticoagulation)

Hypothyroidism

Other rarities such as systemic lupus erythematosus and chronic liver failure

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB)

Ovulatory DUB—a primary endometrial disorder of the molecular mechanisms controlling the volume of blood lost during menstruation

Anovulatory DUB—a primary disorder of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis resulting

in excessive unopposed ovarian estrogen secretion and a secondary endometrial disturbance |

Reproduced from Woolcock et al., 2008, with permission.

The initial step in the evaluation of menstrual disorders involves differentiation between abnormal uterine bleeding caused by ovulatory dysfunction and bleeding secondary to genital lesions or systemic disease states. “Dysfunctional uterine bleeding” is a term that has been applied to abnormal uterine bleeding from irregular or absent ovulation. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is a diagnosis of exclusion after determining that organic causes are not involved. Organic causes for abnormal uterine bleeding, exclusive of pregnancy-related bleeding, may be classified into three categories: pelvic pathology, systemic disease, and iatrogenic causes. If these organic causes can be excluded, ovulatory disorders are the likely cause of abnormal uterine bleeding.

Anovulatory bleeding is most commonly encountered at the beginning and end of the reproductive years. The immaturity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis causes infrequent ovulation and irregular uterine bleeding in the peripubertal years, while irregular bleeding during the menopausal transition is encountered with the oocyte depletion of diminishing ovarian reserve.

The World Health Organization (WHO) proposed a practical classification for disorders of ovulation. The WHO designated three groups (I, II, III) based on the state of gonadotropin and estrogen secretion. The diagnosis of hypogonadotropic (low luteinizing hormone [LH] and follicle-stimulating hormone [FSH]) and hypoestrogenic anovulation (WHO group I) is often referred to as hypothalamic anovulation. The WHO group I disorders result from a variety of stressors or primary disease states that impact the hypothalamus to alter gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulsatility, with disruption of cyclic gonadotropin release. Hypothalamic anovulation may result from a congenital disorder of formation of the neurons that secrete GnRH, but also could be secondary to organic lesions of the brain or stress from psychological or other disease states.

Hypergonadotropic anovulation (WHO group III; high LH and FSH) is related to follicle and oocyte depletion. This grouping comprises women who naturally proceed through the transition to menopause, but also includes women who exhibit primary or secondary ovarian insufficiency, a category often referred to as premature ovarian failure.

The most problematic group of anovulatory disorders to define, however, is WHO group II, the so-called normogonadotropic, normoestrogenic cases. WHO group II, which constitutes by far the largest group of patients, is composed of a variety of hormonal abnormalities, with the largest category representing the polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). The heterogeneity of this group prevents a single unified approach to the diagnosis of specific disorders within the WHO group II designation. Obesity, adrenal and thyroid dysfunction, and particular metabolic diseases can cause inappropriate extragonadal production of estrogen and androgen. This status can “short-circuit” the normal sex steroid feedback mechanism to the hypothalamus and pituitary because inappropriate extragonadal production of estrogen and androgen will produce tonic suppression of the cyclic LH and FSH secretion necessary for ovulation. Therefore, a woman can have a variety of causes for normogonadotropic, normoestrogenic anovulation (WHO group II), and these causes are not elucidated by the measurement of serum estradiol, FSH, and LH. For appropriate management of these patients, the astute diagnostician must carefully solicit pertinent historical information and carefully observe cutaneous, genital, and constitutional signs associated with both normal and abnormal estrogen and androgen production.

Organization of the Book

Disorders of Menstruation is a clinical reference for the medical management of the female with abnormal vaginal bleeding. The chapters are organized sequentially in a chronology from infancy to old age throughout a woman’s life. A given sign, symptom, or finding within a particular age group will often have markedly different health implications. Because the myriad causes of disordered menstruation often have a unique presentation in each age group, there is an intentional overlap of information among chapters to discuss these important distinctions.

The working assumption in this reference is that readers will be looking for advice and information that will assist them in clinical encounters, without overemphasis on the theoretical aspects of approaches and procedures. The authors, however, understand the importance of reviewing the crucial basic science necessary for effective diagnosis and management. The chapters are not heavily referenced, but citations of important reviews and major contributions are provided in the “Selected bibliography” at the end of each chapter.

Information is provided in a format that makes reading easier and allows the busy clinician to quickly access the essential information for patient care. Practical guidance to readers will be provided through the use of algorithms and guidelines where they are appropriate. Key evidence (clinical trials, Cochrane Database citations, other meta-analyses) is summarized in “Evidence at a glance” boxes. “Tips and tricks” boxes provide hints on improving outcomes by indicating practical techniques, pertinent patient questioning, or pertinent signs or symptoms that direct clinical management. The clinical tips may be derived from experience rather than formal evidence, but a rationale is provided to support suggested practices. “Caution” warning boxes suggest hints on avoiding problems, perhaps via a statement of contraindications or by warning of pitfalls in management. “Science revisited” boxes reveal a quick and clear reminder of the basic science principles necessary for understanding principles of practice.

Orientation to the Chapters

Vaginal bleeding in the prepubertal infant and girl signifies an abnormality that demands prompt investigation. Chapter 2, entitled “Prepubertal Genital Bleeding,” defines the best approaches for management of the pediatric population, who often cannot provide a clear history and may be threatened by a sensitive examination. The authors provide a clear and detailed approach to the pertinent gynecologic history and examination of the female child. Their defined approach maximizes the opportunities to make an “office” diagnosis. These clinicians indicate that most causes of prepubertal genital bleeding include trauma, intravaginal foreign bodies, infection, and vulvovaginal dermatologic disorders. Indications of sexual abuse must be confirmed, and the authors emphasize the means to fulfill the legal mandate that clinicians report these incidents to authorities for child protection. The malignant causes of prepubertal genital bleeding are then presented, with specific indications for making a prompt diagnosis and referral. Precocious puberty may present with vaginal bleeding in the pediatric age group. In this case, other signs of premature pubertal progress are seen, which may include the early development of the breasts, axillary and pubic hair, and a growth spurt with associated advanced bone maturation. The details of diagnosis and management of precocious puberty are explored in depth in the next chapter.

Chapter 3, on “Irregular Vaginal Bleeding and Amenorrhea During the Pubertal Years,” provides a comprehensive overview of the normal pubertal milestones and highlights boundaries for when deviation from the normal sequence of female development is a cause for concern. The causes of precocious puberty are first delineated so the diagnosing physician will be armed with the most common elements of the differential diagnosis. This is followed by a direct and practical diagnostic approach that helps in understanding how historical, physical examination, and laboratory findings will allow categorization of the differential causes of precocious puberty into central (above the neck) or peripheral (below the neck) abnormalities. Precocious puberty signifies the potential for serious health and reproductive consequences. The wealth of practical knowledge revealed in this chapter will assist the clinician in the most efficient and accurate method to best manage this emotionally charged situation.

If puberty is delayed, young women and parents need education about whether this condition is within the normal physiologic range of development or whether this represents a condition of primary amenorrhea. The differential diagnosis for primary amenorrhea has significantly different implications when compared to the absence of periods once puberty is complete and menstruation has started (secondary amenorrhea). While certain presenting signs will immediately clue the physician to the origin of the cause of primary amenorrhea (e.g., Turner’s syndrome, müllerian agenesis, androgen insensitivity), other causes are not obvious, and their diagnosis requires a systematic management algorithm that is clearly presented in this chapter.

Menarche heralds the transition from childhood to the reproductively competent woman. Adolescents and their parents, however, are often unsure about what represents normal menstrual patterns after menarche. For the first 18 months after menarche, irregular menstrual bleeding from infrequent ovulation is common. Rarely, however, should the time interval between cycles be greater than 90 days. Amenorrhea for greater than 3 months or menstrual flow for longer than 7 days is abnor...