![]()

PART One

Causes of the Financial Crisis of 2007-2009

Matthew Richardson

There is almost universal agreement that the fundamental cause of the financial crisis was the combination of a credit boom and a housing bubble. It is much less clear, however, why this combination led to such a severe crisis.

The common view is that the crisis was due to the originate-to-distribute model of securitization, which led to lower-quality loans being miraculously transformed into highly rated securities by the rating agencies. To some extent, this characterization is unfortunately true. That is:

• There was a tremendous growth in subprime loans. Many of these loans were highly risky and only possible due to the clever creation of products like 2/28 and 3/27 adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs).

• Moreover, this growth in subprime lending was only possible due to the ability of securitization to pass on the credit risk of loans faced by the lender to the end user investor in asset-backed securities (ABSs).

• The end user was willing to invest only because the rating agencies had rubber-stamped a large portion of these securities as AAA by creating a chain of complex structured products.

Chapter 1, “Mortgage Origination and Securitization in the Financial Crisis,” looks at these issues in detail and lays out principles and proposals for future regulation. Of course, while this chapter focuses on the mortgage market and—in particular—on subprime loans, the discussion holds more generally. There was a plethora of cheap loans made throughout the economy, and many of the same issues of deteriorating loan quality are at play in these other markets. Credit card debt, car loans, “covenant-lite” corporate bonds, and leveraged loans for leveraged buyout (LBO) transactions were all trading at historically low spreads over risk-free bonds. Like the past fate of the subprime market, many of these loans are now facing increasing default rates. For example, default rates on credit card debts may rise to 10 percent in 2009, which is double the 5 percent average of the past 10 years. Car loan delinquencies are on the rise, and financial economists (e.g., NYU Stern School’s Edward Altman) forecast corporate bond delinquencies to double from around 4 percent in 2008 to 8.5 to 9 percent in 2009. The same argument made in Chapter 1 that an increase in securitization reduced screening and monitoring efforts for the lenders in the mortgage market could be made in these other markets as well.

The subprime market, however, has one unique feature relative to these other credit markets. The loans were unwittingly structured to be systemic in nature. To understand this point, note that the majority of subprime loans were structured as hybrid 2/28 or 3/27 ARMs. These loans offered a fixed teaser rate for the first few years (i.e., two or three years) and then adjustable rates thereafter, with a large enough spread to cause a significant jump in the rate. By design, therefore, these mortgages were intended to default in a few years or to be refinanced assuming that the collateral value (i.e., the house price) increased. Because these mortgages were all set around the same time, mortgage lenders had inadvertently created an environment that would lead to either a systemic wave of refinancings or one of defaults.

The growth in structured products across Wall Street during this period was staggering. While residential mortgage-related products were certainly a large component, so too were asset-backed securities using commercial mortgages, leveraged loans, corporate bonds, student loans, and so forth. For example, according to Asset-Backed Alert, securitization worldwide went from $767 billion at the end of 2001 to $1.4 trillion in 2004 to $2.7 trillion at the peak of the bubble in December 2006. It has fallen dramatically over the past few years, with the drop being over 60 percent from the third quarter of 2007 to the third quarter of 2008. A common feature of most of these structures was that the rating agencies sanctioned the products (and their credit risk) by providing ratings for the different tranches within these securities. It is very clear that the greatest demand for these products came through the creation of the AAA-rated tranches that would appeal to a host of potential investors. Since the rating agencies described the tranche ratings as comparable to other rating classes, their role in this process cannot be overlooked. To this end, Chapter 3, “The Rating Agencies: Is Regulation the Answer?” describes the history of how the rating agencies were formed, their role in the current crisis, and suggestions with respect to future regulation.

Nevertheless, we believe that, although the originate-to-distribute model of securitization and the rating agencies were clearly important factors, the financial crisis occurred because financial institutions did not follow the business model of securitization. Rather than acting as intermediaries by transferring the risk from mortgage lenders to capital market investors, these institutions themselves took on this investment role. But unlike a typical pension fund, fixed income mutual fund, or sovereign wealth fund, financial firms are highly levered institutions. Given regulatory oversight, how did the major financial firms manage to do this, and perhaps more important, why did they do it?

Chapter 2, “How Banks Played the Leverage Game,” addresses the former question. Specifically, in order to stretch their capital requirements, commercial banks set up off-balance-sheet asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) conduits and structured investment vehicles (SIVs), where they transferred some of the assets they would have otherwise held on their books. ABCPs and SIVs were funded with small amounts of equity and the rolling over of short-term debt. These conduits had credit enhancements that were recourse back to the banks. Investment banks, however, did not have to be so clever. Following the investment banks’ request in the spring of 2004, in August of that year the SEC amended the net capital rule of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. This amendment effectively allowed the investment banks to lever up, albeit with potentially more scrutiny by the SEC.

With now much higher leverage ratios, financial firms had to address the likely increase in their value at risk. The firms found relief by switching away from loans into investments in the form of AAA-rated tranches of collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) and collateralized loan obligations (CLOs). These highly rated CDOs and CLOs had a significantly lower capital charge. In fact, about 30 percent of all AAA asset-backed securities remained within the banking system, and if one includes ABCP conduits and SIVs that had recourse, this fraction rises to 50 percent.

Why asset-backed securities? At the peak of the housing bubble in June 2006, AAA-rated subprime CDOs offered twice the premium on the typical AAA credit default swap of a corporation. Therefore, financial firms would be earning a higher premium most of the time; by construction, losses would occur only if the AAA tranche of the CDO got hit. If this rare event occurred, however, it would almost surely be a systemic shock affecting all markets. In effect, financial firms were writing a large number of deeply out-of-the-money put options on the housing market. Of course, the problem with writing huge amounts of systemic insurance like this is that the firms cannot make good when it counts—hence, the financial crisis.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Mortgage Origination and Securitization in the Financial Crisis

Dwight Jaffee, Anthony W. Lynch, Matthew Richardson,

and Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh

1.1 INTRODUCTION: THE U.S. MORTGAGE MARKET

There are three main types of mortgages: fixed rate mortgages (FRMs), adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs), and hybrids. ARMs have an adjusting interest rate tied to an index, whereas hybrids typically offer a fixed rate for a prespecified number of years before the rate becomes adjustable for the remainder of the loan. Mortgage loans fall into two categories, prime and nonprime. We discuss each category in turn.

Prime Mortgages

There are three main types of prime mortgages. Loans that conform to the guidelines used by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac for buying loans are known as conforming loans. The guidelines include a loan limit, currently $417,000 for one-family loans, and underwriting criteria on credit score (FICO score), combined loan-to-value ratio and debt-to-income ratio. Loans that roughly conform to all the guidelines for a conforming loan except the loan limit are known as jumbo loans. The interest rate charged on jumbo mortgage loans is generally higher than that charged on conforming loans, most likely due to the slightly higher cost of securitizing such loans without the implicit government guarantee that backs conforming-loan mortgage-backed securities (MBSs). The third type of prime mortgages is FHA/VA loans. FHA loans are insured by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and may be issued by federally qualified lenders. The FHA primarily serves people who cannot afford a conventional down payment or otherwise do not qualify for private mortgage insurance. VA loans are guaranteed by the Department of Veterans Affairs and are available to veterans and military personnel. FHA/VA loans are also regarded as conforming loans.

Nonprime Mortgages

There are three main types of nonprime mortgages. Although there is no standardized definition, subprime loans are usually classified in the United States as those where the borrower has a credit (FICO) score below a particular level and whose rate is much higher than that for prime loans. Alt-A loans are considered riskier than prime loans but less risky than subprime loans. Alt-A borrowers pay higher rates than prime borrowers but much lower rates than subprime borrowers. With an Alt-A loan, the borrower’s credit score is not quite high enough for a conforming loan, or the borrower has not fully documented his or her application, or there is something a little out of the ordinary with the deal. Lender criteria for Alt-A vary, with credit score requirements being the most common area of variance. Finally, a home equity loan (HEL) or home equity line of credit (HELOC) is typically a second-lien loan. A HELOC loan differs from a conventional mortgage loan in that the borrower is not advanced the entire sum up front, but uses a line of credit to borrow sums that total no more than the agreed amount, similar to a credit card and usually with an adjustable rate. In contrast, a HEL is a one-time lump-sum loan, often with a fixed interest rate.

Securitization

Securitization in the mortgage market involves the pooling of mortgages into mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) in which the holder of these securities is entitled to some fraction of all the interest and principal paid out by the portfolio of loans. Some of these securities are straight pass-throughs, while others are collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs) or collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) in which the pools are tranched and cash flows get paid out according to some priority structure. The size of the residential mortgage market in the United States is well over $10 trillion, with over 55 percent of it being securitized. Interestingly, after explosive growth in the 1980s with the development of mortgage-backed pass-throughs and CMOs, the fraction of securitization has held relatively constant since the early 1990s, hovering between 50 percent and 60 percent.

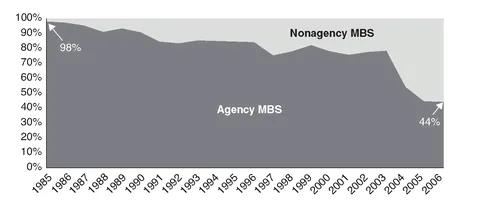

FIGURE 1.1 Nonagency Securitized Mortgage Issuance, 1985-2006

This chart presents the percentage of securitization issuance coming from nonagency mortgage-backed securities (MBSs). Nonagency MBSs include private-label jumbo, Alt-A, and mortgage-related ABSs.

Source: FDIC, UBS, PIMCO.

Government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) purchase and securitize mortgages. While GSEs are privately funded, their government sponsorship implies a presumption that their guarantor function is fully backed by the U.S. government. There are three GSEs: the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae); the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac); and the Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) system consisting of 12 regional banks. The contribution of the GSEs to securitization of mortgages is startling. In the early 1980s, agency MBSs represented approximately 50 percent of the securitized market, by 1992 a 64 percent share, and by 2002 a 73 percent share.

However, after 2002, the mortgage market and, in particular, the securitization market changed dramatically, with nonagency MBSs representing 15 percent in 2003, 23 percent in 2004, 31 percent in 2005, and 32 percent in 2006 of the total securities outstanding. In fact, in terms of new issuance of MBSs, the share of nonagency securitization was for the first time larger than that of agency-backed securitization, reaching 56 percent in 2006. A considerable portion of this issuance consisted of subprime and Alt-A loans. Figure 1.1 illustrates these points.

1.2 SOME SALIENT FACTS

In this section, we describe some of the important characteristics of the mortgage market and securitization of this market over the period 2001 to 2007.

The Mortgage Market

There has been enormous growth in nonprime mortgages. Table 1.1 reports data on the size of the U.S. mortgage market from 2001 to 2006. Nonprime mortgage originations (subprime, Alt-A, and HELOCs) were more than $1 trillion annually in 2004, 2005, and 2006. They rose as a share of total originations from 14 percent in 2001 to 48 percent in 2006. Many of these subprime loans were adjustable rate loans, due to be reset in the period 2007-2009, which may be part of the reason for the foreclosure crisis.

The quality of mortgages has declined considerably over the past five years. From 2002 to 2006, loan-to-value ratios increased dramatically in all three major loan categories (prime, Alt-A, and subprime), while the prevalence of loans with full documentation decreased dramatically. At the same time, debt-to-income ratios increased dramatically only for prime loans, while FICO scores were largely unaffected in all major loan categories. The following numbers are taken from Zimmerman (2007) and the data source is Loan Performance data.

• There has been substantial growth in the average combined loan-to-value (CLTV) ratio of loans in all three major loan categories. For prime ARMs, this ratio has increased from 66.4 percent in 2002 to 75.3 percent in 2006, while for Alt-A ARMs, it has increased from 74.3 percent i...