![]()

01

The car – fashion item or out of fashion?

For many decades, starting in the 1930s and with a golden era in the 1950s and 1960s, the car had a central role in society as a means of transport and as a symbol of status, affluence and personal freedom. Popular culture and public policies, with relatively few exceptions, supported the car and its strong role in society. In recent years, however, the car has been questioned for a number of reasons including its impact on the environment, and increasing traffic which results in traffic agglomerations and jams, particularly in bigger cities. Consumers have turned their interest to other products and have accordingly transferred their purchasing power to other areas: cheap travel abroad, housing and hobbies, to name a few examples.

That cars may cause problems is not a new phenomenon. It has been extensively dealt with in modern history (Lutz and Fernandez, 2010). In 1914, the mayor of Cali, Colombia, decided to regulate the impact of cars since they were – even though only in the hands of rich people – causing a lot of problems. According to the mayor:

unfortunately, it is an evident fact that quite a few young men and persons of notoriety use the automobile at night to associate with women of ill repute, sometimes accompanied by minors, and they drive about town, especially in the rougher neighbourhoods, singing lewd songs, drinking heavily, making a racket, and disturbing citizens, who cannot sleep, while these people are involved in all manner of racy behaviour.

(Giucci, 2012)

The ‘branded society’ and an increase in promoting the brand experience throughout the entire customer purchase process have also gained more attention in recent years. This chapter will discuss the impact of brand focus and aestheticization on the car industry and how companies can deal with this.

How the car lost its advantage – emotional and functional rationales

Companies in the car industry must understand the move towards a branded society and the transition of the car from having a place in popular culture to the current situation in many markets where a decreasing percentage of young people have a driving licence and there is a strong lobby against the car. The internet has contributed to the fundamental change in consumers’ attitudes (particularly amongst the young) to transport, where and how to live their lives, and what constitutes a status symbol. This change would be hard to reverse. Proactive car companies can take advantage of the situation by gaining key insights into how actors in the car industry and in other sectors have benefited from the changes in the market and launched new concepts that delight customers, improve industry reputation and create sustainable competitive advantages.

In big markets such as China, India and some countries in South America and the Middle East, the car still has a strong role as a symbol of freedom, status and affluence. But there may be an opportunity to regain a strong position for the car in people’s everyday lives where it has been diminishing recently. When the car is being questioned by different stakeholder groups, calculations on the costs of cars for society are made – a very complex task, often strongly influenced by the interests at hand. It’s hard to imagine a society without cars, so it’s difficult to calculate the implications of cars from a pure cost-benefit perspective. It has been suggested that fuel taxes in the United States cover about two-thirds of highway construction and repair costs, but little of the cost to construct or repair local roads. But cars also take up space that could be used for other applications, and traffic police enforcement, pollution and road maintenance are all costs that should be considered against all the benefits that car driving generates in terms of social mobility, economic growth and individualized welfare for the masses.

Cars have always been expensive to own and drive. Although many people hark back to the period before the oil crisis in the early 1970s, or the Gulf war in 1990–91, when fuel was cheaper, the fact remains: even if fuel was cheaper then, there have always been high costs involved in owning and driving cars. Cars are highly depreciating items, insurance is expensive, taxes are significant, inspections/servicing is expensive and there are significant costs involved in finance, maintenance and parking. These high costs contribute to the car’s role as status symbol. Another key explanation is the car’s promise of freedom, something that has been extensively restricted over the years.

In Europe, 15 million cars were sold in 2007; in 2013 it will be fewer than 12 million, and 2014 is expected to be even lower (LMC Automotive’s). It’s easy, like many automotive managers do, to blame a recession, the end of scrappage bonuses to stimulate new cars sales, high taxes and high unemployment rates. But the future is more complicated. Consumers have many more choices when it comes to spending their money and the car has largely lost its role as a status symbol. Cars are increasingly associated with problems and costs – and less with freedom, status and dreams.

Urbanization contributes to the problems. According to OECD, 86 per cent of the rich people in the world will live in big cities in 2050, compared to 77 per cent in 2010. The number of households without a car will increase, and car pools will expand at the cost of individuals having their own cars.

If successful, progressive families back in the 1950s and 1960s were portrayed with and around the car: it’s now more likely to be a picture without a car in sight – but maybe a newly renovated kitchen, a man cooking, a woman working in an architect-designed garden, or children playing. When the car’s status goes down, brands like Dacia, Skoda and Kia are likely to benefit: there is no shame in driving these brands any more. It rather reflects buyers being modern and balanced in the way they related to cars.

BMW is one of the few auto brands that have been extensively involved in understanding changes in society and the business environment. It has started an organization that works with mobility of the future and through acquisitions has access to the latest developments; for instance, New York-based ‘My City Way’, a company that provides real-time traffic updates.

Changes in societal values and the role of the car

The car has always been strongly related to individualistic ideologies. While right-wing politicians have emphasized the freedom aspect of car use and the importance of the car for economic growth and business development, left-wing politicians have emphasized the functional qualities of the car, but also the environmental and social problems it causes: cars may even create social isolation in a society built around cars when socio-economic groups that can’t afford a car have limited opportunities to take part in different societal activities. Without a car, visiting a DIY store, travelling to Yosemite National Park or seeing friends in their summer homes may be very difficult.

Every generational cohort is programmed from birth. The coming-of-age assumption holds that early years shape a generation’s values and behavioural traits, but with particular influence during the years from 17 to 23 (Parment, 2011a; 2013, Schewe et al, 2013). This means that individuals born in the 1980s and 1990s grew up in a society that in many respects is different from the one that earlier generations grew up in. Although societies differ substantially across nations and continents, there are some general patterns that describe the development from a global perspective, or at least from the perspective of developed countries. Some of the changes are rather obvious, eg that the young generational cohort grew up surrounded by the internet and new tools to communicate and make friends: mobile phones and a multitude of TV channels became available to just about everybody. This change laid the foundation of the emergence of social media, a key tool in setting up a marketing communications mix that appeals to young individuals in particular. But there are other more fundamental shifts in society that may be derived from less obvious events and trends.

As with other vehicles, automobiles have been incorporated into artworks including music, books and movies. Between 1905 and 1908, more than 120 songs were written in which the automobile was the subject (Jackson, 1985). Until the 1980s, and later to an extent, the car and the culture around the car lay the foundation of many movies. Many movies with the car as a significant part of the story have provided heroes who found freedom rather than duty and hierarchy on the open road. More recently, many changes in popular culture have taken place. New television programmes have given new perspectives on life. This change was very significant in Eastern Europe where television had been state-controlled. For political reasons, opportunities to take part in a Western lifestyle were limited. In these countries, democratization, market forces and the opportunity to adapt to a Western-oriented lifestyle with consumption at its heart came largely at the same time. In Scandinavia, television was also to a large extent state-owned but showed a selection of largely harmless television programmes from the United States and Western Europe – ‘Dallas’ and ‘Dynasty’, ‘Cosby’ and ‘Seinfeld’ were shown. At the end of the 1980s, the state eased control in many countries and gave room to commercial television channels. In the 1990s, most major programmes were available throughout the Western world. A multitude of programmes were now available: MTV made pop music videos available around the clock; sitcoms such as ‘Frasier’; talk shows with Johnny Carson, David Letterman and Jay Leno; and programmes that promoted a glamorous lifestyle, such as ‘Sex and the City’, emerged. The latter particularly appears to have a strong impact on the values of individuals who grew up during the 1990s. In interviews with the Generation Y cohort (those born in the 1980s) there are many references to ‘Sex and the City’, ‘Beverly Hills’ and later ‘Gossip Girl’ and ‘The Hills’, to name a few. (See Parment, 2011a, for a further investigation of the influence of popular culture.)

Popular culture often has its roots in metro areas. Increasingly, in portrayals of a glamorous lifestyle there is little evidence of cars. Metro areas are generally portrayed as desirable and glamorous while rural areas are portrayed as undesirable, so the popular culture has made a significant contribution to one of the car industry’s challenges: urbanization. In Times Square in New York, there is much less room for cars now than there used to be: more space is given over to pedestrians, socializing and electronic signs, all being significant aspects of metro living.

(Anders Parment, 4 March 2009, Times Square, New York)

What do these influences, which together are strong in terms of how individuals’ values are shaped, have in common? They portray a glamorous lifestyle to teenagers and young adults across the Western world, and now also to other parts of the world. In the lifestyle portrayed there is little evidence of cars, something that reflects a gradual reduction in focus on cars in movies, sales promotions, celebrity exposition, television programmes, etc. In addition, metro areas are portrayed as desirable and glamorous while rural areas are portrayed as generally undesirable, so popular culture has made a significant contribution to one of the car industry’s challenges: urbanization. The message to young individuals is clear: if you live in a rural area, you should move to a bigger place with more opportunities, glamour, tolerance and choices. Hence, popular culture has largely contributed not only to urbanization, but also to aestheticization, and a stronger emphasis on brands – individuals who grow up in metro areas face substantially more brand messages than those growing up in rural areas. In addition, the role of the car is different in metro areas: it’s less important, both for transport and from an image perspective as there are other arenas that compete for attention.

Metro areas provide an array of opportunities, and living without a car is not only an option – it may make life easier due to the high costs and inconveniences car ownership and use entail in metro areas. For young individuals in particular, the car is less important, both for transport and in terms of image.

(Anders Parment, 29 May 2009, Comedy Theatre, St Petersburg, Russia)

Fewer young people have a driving licence

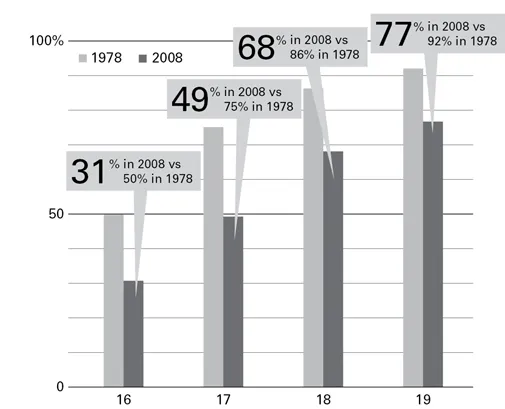

A young interviewee argued that there is no reason to have a driver’s licence any more – ‘If you have seen “Sex and the City”, you know how young people want to live, and they don’t want to drive their own cars, they want to walk or go by cab.’ The car, once a rite of passage for US youth, is becoming less relevant to a growing number of young individuals, something that could have broad implications for the car industry – and many other industries with a strong stake in car transport, such as insurance, fuel and out-of-town shopping areas. In 1978, in the United States 50 per cent of 16-year-olds had a driver’s licence and 92 per cent of 19-year-olds – now the shares are 31 and 77 per cent, respectively (Neff, 2010). Certainly it’s hard to believe for anyone stuck in traffic on the way to O’Hare airport in Chicago, on a bridge or tunnel into Manhattan, or on any freeway in Los Angeles – but the pattern is clear: the average age of drivers is increasing year by year, thus making the ability to drive less of a symbol for young people.

FIGURE 1.1 Percentage of US population aged between 16 and 19 with a driver’s licence in 1978 and 2008

SOURCE: US Department of Transportation

Even though population growth in the United States is, thanks to immigration, among the highest in industrialized countries at 0.9 per cent per year (CIA World Factbook, 2012)1, the number of miles driven annually on US roads began to decrease in 2004 (Davis et al, 2012; Motavalli, 2013). The number of miles driven per person decreased by 6 per cent between 2004 and 2011, primarily down to young people: between 2001 and 2009, the average number of miles per year driven by 16–34-year-olds decreased by 23 per cent – from 10,300 to 7,900 miles per capita. A full driving licence for cars is available by the age of 16 in most US states – 15 or 17 in others and, in North and South Dakota, 14 years and six months!

Similar tendencies have been found in many other countries with the number of citizens with a driver’s licence going down and driving rates fal...