![]()

PART ONE

Change in context

![]()

02

The electrical revolution that never was

We talk endlessly of change in the business world, but not that much is different. We still pay for things more with cash than with fingerprints. It’s not that we don’t have the paperless office quite yet; it’s that we’ve never used more paper than we do today (Schwartz, 2012). Texting has been here for more than 20 years, but I can’t use instant messaging to change a flight. E-mail isn’t remotely new, yet I can’t e-mail my bank. Mortgages are given to those with a steady work history and reams of paperwork, not those who’ve created a start-up that’s exploding or who live a nomadic life. The world hasn’t changed as much as we like to think it has. In particular, we’ve failed to really understand the power of digital. In this chapter I want to go back in time and, by understanding mistakes from the past, learn how best to approach today.

For over four decades electricity spread purposefully and slowly across the world, bringing small incremental changes to factories and homes, but not adding anything transformative. Most years, small incremental changes kept factory managers happy and domestic lives seemed to improve nicely. But it’s only in retrospect that we can see how the transformative power of electricity was not properly harnessed.

From factory owners to workers, home owners to retailers, each and every single person thought they’d understood this new technology, and thought they’d made the necessary changes. They seemed to treat electricity as a new thing to bolt on to the side, a tweak based on small improvements, never truly digesting the meaning of this technology and working around the new possibilities it offered. It’s this paradox of transformative potential vs actual change that should concern everyone in any business today.

The hard sell of electricity

It was 600 BC when the Ancient Greeks found that rubbing fur on amber (fossilized tree resin) caused an attraction between the two, and discovered static electricity. But it was only in 1831 that Michael Faraday first began generating power in a consistent, practical way. It was not long before the current was reversed and the first electric motor was born. One would expect something quite so transformative to have a near immediate effect on the world, but this was not the case. Much like the early internet, few could see the meaning at the start.

Lighting was one of the first clear and obvious applications of electricity, but it still took up to 20 years to be refined into something that was more illuminator and less fire hazard than its first iterations. By 1850, 29 years into the first steady production of electricity, the National Gallery in London as well as lighthouses around the UK coastline were lit up by electrical bulbs (The Victorian Emporium, 2011). This wasn’t exactly life-changing.

Demand for electric power in households was best described as slight. Electricity was a hard sell and by the late 1800s only a very small percentage of domestic dwellings had electricity. Like most new technology it was first sold to wealthy homes as something of a gadget: first as a better way to light Christmas trees, and then a better way to light homes. In an era when the wealthy were not bothered about the workload and mental burden placed on their staff, electricity didn’t seem that helpful. It was complex too. Businesses sought to take advantage of the little growth there was by trying to create their own walled gardens. A number of closed and non-compatible systems cropped up. As there was no industry-standard equipment, anyone, whether business owner, public building manager or wealthy home owner, could ask a company such as Edison or his competitors to create a custom system for their needs. Little equipment was interchangeable between makers.

The main issue remained demand. The lack of demonstrably exciting use cases meant electrical power was largely pushed onto people, not pulled by thirsty would-be customers. People buy and want solutions, not technologies. The early demise of curved TVs or Amstrad video phones shows that, unless gadgets manifest themselves as wonderful, valuable or helpful use cases, they remain frivolous and wither. The spread of electricity was slow because the use cases were underwhelming. Nobody created anything new around electrical power. The world merely took existing items and considered how they could be ‘electrified’.

There was effectively no new thinking at all. We replicated the past in electrical form with no imagination; we even replicated the limitations. Gas and oil lighting had always been controlled at the light ‘fixture’ itself – you’d walk into a dark room, use a match to locate the light fixture and light it by hand. So the standard way to turn on electric lights was the same – use a match to find the hanging fixture and turn a switch at the base of the bulb. The idea of a wall-mounted light switch never occurred to early adopters, and then, when it was finally proposed, seemed a rather lavish and expensive feature.

A lack of both power sockets and devices to plug into them caused a curious vicious circle. How could you plug something in that had yet to be invented? And how could you create something that couldn’t easily access power? The first home goods to appear were washing machines, electric vacuum cleaners, electric irons, electric refrigerators, bread toasters, and tea kettles. Slowly over time new items were invented for the electrical age and changed our relationship with electricity. Electric fans and radiant heaters created the first expectations of climate control, and electric hair dryers, telephones and radios started broadening out electricity’s uses from the mere functional running of a household to really improving lifestyle.

The key way to think about power in the home was that it had many phases. First, an era of people discovering and refining a technology so that it could be used. Then a period when it was only for the rich, when its possibilities were hard to recognize, when we added power to old items to improve their functionality. Finally, a period when the technology plummeted in price, became far more accessible to all, but above all else, this was when new items were created around the potential of the technology. What started out as a way to make our Christmas trees easier for our servants to light became a technology that freed the middle classes from the hard work of running a house and put millions of women into the workforce.

Electrification of factories

Compared with the slow uptake of electricity for domestic use, and the lack of excitement that accompanied it, the electrification of factories was rapid and easily achieved. To best understand how electrical power was adopted in industry we must first understand how, where and why factories were built and how they were laid out and constructed.

The line drive system

Factories constructed from the 18th century onwards, during the Industrial Revolution, were built around a power system based on a ‘line drive shaft’, a huge, long, spinning shaft that would directly or indirectly power all the equipment in a factory layout. In the very first factories, this shaft was turned by water power, with waterwheels converting flowing water into an energy source. Over the course of the 18th century steam engines developed into the preferred source of power. Steam provided more torque and far more energy, was more controllable and allowed factories to be constructed anywhere people wished, so long as coal could be easily delivered in large quantities. The first use of steam engines, rather remarkably, wasn’t to directly power equipment in factories, but oddly to pump water upwards to storage reservoirs to enable waterwheels to operate. It’s incredible how we tend to apply new technology to old systems.

The line drive shaft dominated the layout of the factory. Running the entire length of any plant, it dictated virtually every aspect of the plant’s design. Factories were long rectangular shapes, to ensure that all the equipment could pull power from it. Walls were massive and heavy to hold the weight of it. Huge iron reinforcement was needed, making factory construction extremely expensive. Windows for light or ventilation were very hard to make, and single-storey construction was by far the most sensible.

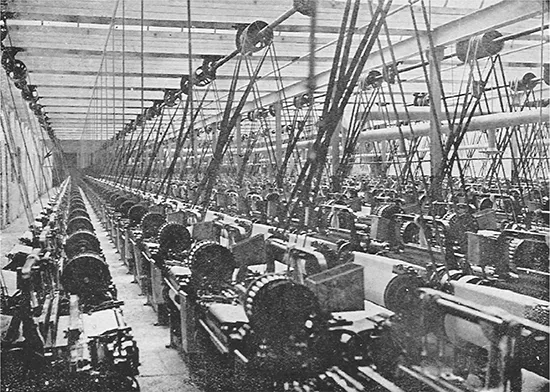

From the line shaft, a complex system of belts, pulleys and gears known as ‘millwork’, as illustrated in Figure 2.1, would ensure that all machines could be driven by the power source and would allow a small degree of control. It was possible to remove power, apply it and sometimes change the speed, all with the mere pulling of a vast lever!

Figure 2.1 A cotton mill in Lancashire, 1914

A cotton mill in Lancashire, 1914 SOURCE http://www.wikiwand.com/en/Cotton_mill

Designing factories was a difficult task. Fabrication machines were not arranged in the most efficient way for the manufacture of goods, but on the most sensible layout of the machines relative to the line drive shaft. Machines requiring similar torque, speed of rotation and operating times were placed together. The vast amount of space taken up by the machines themselves, the products being made and the needs of the millwork meant that factories were incredibly tight spaces, with products frequently moving around as they made their way through the production process.

Looking at Figure 2.1, showing a typical factory in Lancashire in 1914, we can only imagine what a hazardous place this would have been in which to work: steam engines producing incredible heat and noise; huge spinning shafts making deafening noise; vibrating equipment making everything shake; no ventilation to remove heat or smells, and certainly very little natural light. Above all else, seemingly endless arrays of pulleys, belts and shafts created an extremely dangerous working environment.

The electrical shift

Factories knew how to adapt to new power sources: it had been done before. The transition from water to steam power in the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s, first in mines, then slowly in mills, had been smooth, as existing factories with water power systems simply built on steam plants and changed the drive mechanism. New factories took the same template and built anywhere steam plants made sense.

As late as 1900 the world still considered the shift to electricity and electrical motors in the same way. By that date, less than 5 per c...