eBook - ePub

Prostitution in Victorian Colchester

Controlling the Uncontrollable

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The decision to build a new army camp in the small market town of Colchester in 1856 was well received and helped to stimulate the local economy after a prolonged period of economic stagnation. Before long the Colchester garrison was one of the largest in the country and the town experienced an economic upturn as well as benefiting from the many social events organised by officers. But there was a downside: some of the soldiers' behavior was highly disruptive and, since very few private soldiers were allowed to marry, prostitution flourished. As a result the number of cases of venereal disease soared. Having compiled a database of nearly 350 of Colchester's nineteenth-century prostitutes, the authors examine how they lived and operated and who their customers were. What were the routes into and out of prostitution and what was life like as a prostitute? Was it even seen by some as an acceptable way for girls and young women to boost inadequate earnings from more respectable work? How did prostitution intersect with the social life of the town, especially as this was played out in local beerhouses? This is also an investigation of how authority in its many guises – from policeman and solicitor to magistrate and lady reformer – dealt with prostitution and the many problems associated with it, bringing a great many vested interests into conflict with each other. Such large numbers of women could not be tidied away into a discreet red-light district but lived and worked all over the town. They gave the police considerable trouble, but it was routinely declared that nothing could be done about them. Prostitution itself was not illegal whilst efforts to tackle the women's criminal activity, such as soliciting, theft or assault, were largely ineffective. Under pressure from the army, Parliament passed the Contagious Diseases Acts, allowing prostitutes affected with venereal symptoms in garrison towns to be confined for treatment, but there was widespread opposition to these controversial laws. Bringing to bear considerations of class and gender, urban development, health and welfare, religion and moral reform, this is a wide-ranging, detailed and original study. As well as providing a vivid portrait of nineteenth-century Colchester, it will appeal to all those interested in the history of women's work, policing and society more widely.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Prostitution in Victorian Colchester by Jane Pearson,Maria Rayner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Britische Geschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Colchester’s Victorian garrison

There is not much to be said about soldiers’ women. They are simply low and cheap, often diseased, and as a class do infinite harm to the service.1

Colchester’s Victorian garrison was started in 1856. This chapter considers its impact on the town, both positive and negative. The army had its own rules and regulations that were outside the town’s jurisdiction. The soldiers were free to roam when off duty and to patronise the town’s leisure outlets, and they also went quite far afield to neighbouring towns and villages. They caused problems of law and order as well as public decency when they stripped off to swim in the river or lay with a prostitute in a field. But because the garrison also provided economic opportunities the town’s authorities were unwilling to be censorious and preferred to negotiate with the garrison, encouraging the CO to assist the town where possible to keep the costs of policing down. In addition, the garrison’s officers provided sporting and cultural events and social activities which many in the town enjoyed.

Colchester was used to the presence of soldiers on its streets well before the Victorian garrison’s personnel arrived in the town in 1856 because the Essex Militia assembled there every summer for training lasting about two months. In May 1853 a public meeting was called to discuss how to instruct and entertain the 800 militia who were about to arrive, and a committee was set up. The committee secretary, a Crouch Street schoolmaster named Samuel Bradnack, contributed some of his ‘young gentlemen’ pupils to instruct the militia in reading, writing and accounts. He may have regretted this as, two years later, he described the militia as ‘the heathen of Essex … their notions of religion are not much in advance of the South Sea islanders’. He claimed that fewer than 100 of them could read and write and he disapproved of their enjoyment of the ‘ribaldry, obscenity and sensuality of the taproom’.2 Subsequently the militia’s annual training often took place in the new garrison.

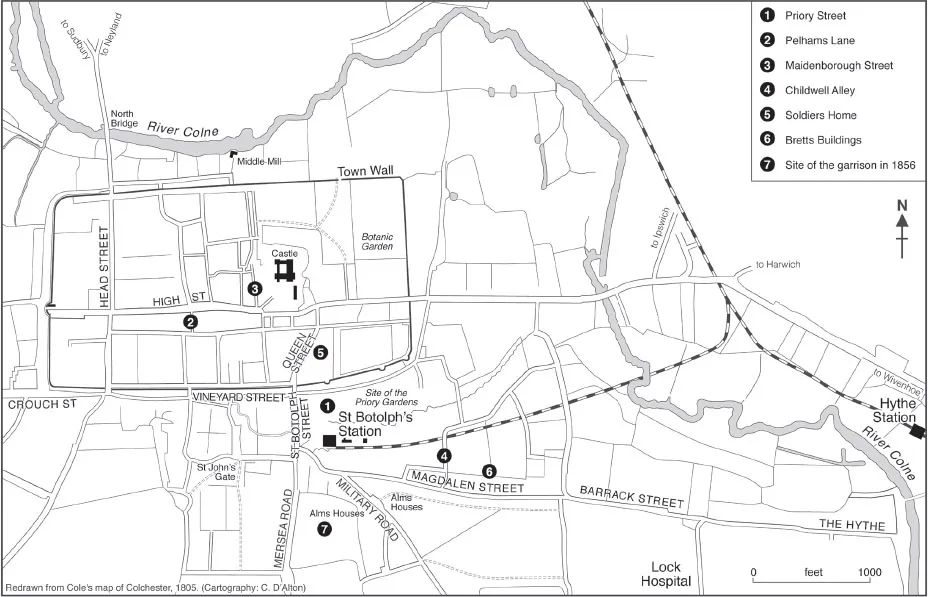

The War Office owned two sites in Colchester. One was the Old Barrack Ground off Port Lane. This had been the site of the Napoleonic barracks and was leased as a smallholding and cricket ground once the barrack huts were cleared after 1815. The other site was the Ordnance Field between Military Road and Butt Road. Together these two sites comprised about 45 acres, which proved to be insufficient as the garrison expanded. The War Office subsequently bought several farms in the vicinity to supply training grounds. The garrison used the Old Barrack Ground for several specific purposes. One was as a space to erect tents to provide extra billets when the camp was full. For instance, tents here accommodated 2,000 German Legion soldiers returning from the Crimea in the summer of 1856. Another was as the site of the lock hospital, erected in 1869 as a result of the Contagious Diseases Acts (CDAs). This hospital imprisoned prostitutes thought to be suffering from venereal disease, as explained in Chapter 6. The field was also sometimes used for drill and sporting purposes.

The Ordnance Field was the site of the camp. Wooden barrack huts were built here sufficient to house 3,000 men. Although the huts were erected with double walls by Messrs Lucas of Ipswich it seems that they were intended as temporary structures. A letter printed 12 years later from a ‘shivering soldier’ complained that the huts were situated ‘on the highest hill in Essex’ and that they were already worn out, the wind whistling through them as if they were paper. Nevertheless, they remained in use for nearly 40 years, being eventually demolished in 1893.3 Contemporary photographs show the huts separated by wide gravel walks and with a parade ground to one side. The new barracks was, in accordance with army tradition, ‘opened’ by a regiment of the line, the 11th Foot, who arrived by train from Brecon and marched from the station ‘with bristling bayonets and the strains of animating music’.4

Figure 3. Colchester Camp from The Queen’s Album (Rock & Co, c.1880).

Figure 4. Map of Colchester showing the Roman walls, the site of the 1856 garrison and some of the streets associated with prostitution.

Initially the camp accommodation was intended for unmarried soldiers but permanent married quarters were hurriedly organised in 1862 to reduce the need for army family lodgings in town. A camp school for 200 children and a lying-in hospital were also provided.5 In 1862 brick cavalry barracks over stables were built off Butt Road, with an artillery barracks and a military prison added a few years later. By 1866, when Colchester became the headquarters for the newly created Eastern Division, it was among the four largest garrisons in the country.

Private soldiers were paid a basic wage of 8s a week, out of which they had to contribute to their food and equipment; as Skelley points out, the Victorian army could compete only with the lowest-paid civilian occupations. In addition, although extra could be earned through good conduct and undertaking extra duties, there were also deductions for goods and services.6 A letter published in the Standard recalled income and outgoings in soldiers’ pay in 1860 as in perfect balance – £1 13s 7d on each side of the balance sheet per year. The letter writer had been paid one shilling a day plus 2s 7d ‘liquor money’, out of which he had to pay for commissariat rations, extra messing, washing, sheet washing, hair cutting, library, barrack damages and regimental (uniform) charges.7

The primitive living conditions to which soldiers were subjected became something of a national scandal when The Times sent its correspondent William Russell to the Crimea to report on the war there in 1854. In a series of articles Russell exposed the squalor in which soldiers were accustomed to live and the deplorable army medical services, which were poorly organised, poorly prioritised and badly planned, and which also suffered from insufficient staff and supplies. Public outrage arising from Russell’s exposé motivated the government and the army to make attempts to improve soldiers’ health, and barracks accommodation was gradually improved over the next four decades. Any bureaucratic reluctance in this area was challenged by periodic scandals when fatal epidemics swept through insanitary barracks in various parts of the country. As Skelley has pointed out, military service was not conducive to health and military medics were not skilled at screening recruits, both of which contributed to a higher than average death rate among peacetime soldiers.8

There was one health issue in particular that caused the army special problems – venereal disease. As explained below, most soldiers were not allowed to marry but neither did the army expect them to be chaste. Pearsall argues that the army authorities tended to regard service men infected with venereal disease with indifference and that army officers assumed that the common soldier would sooner or later contract venereal infection.9 This may have been true, but in the 1850s the rate of army man-hours lost to venereal disease became critical. The 1857 Royal Commission Report on the health of the army, which considered the effect of venereal disease on service men, collected information on its prevalence among troops (including those in Colchester camp), highlighting how frequently soldiers and sailors concealed their affliction, making treatment options more severe and any improvement more difficult to achieve (see Chapter 6).10

Colchester’s new garrison did not emerge well from this investigation. Then, in 1862, an army medical report provided even more worrying statistics on the occurrence and effect of this disease among soldiers. The report presented the figures in terms of the ratio per 1,000 of mean (average) strength of service men suffering from venereal disease which, in Colchester, was particularly high at 464. In comparison, ‘the number (elsewhere) constantly sick in hospital with venereal disease was 1,739, or 22.24 per 1,000 per mean strength’. The report went on to calculate the effect this loss of manpower through illness had on the army:

From these data we deduce the average duration of cases to have been 24.61 days, and the total inefficiency from these cases to have been equal to the loss of the services of every man in the Home force for 8.12 days or the constant loss of upwards of two regiments for the whole year.11

Colchester garrison had the worst record in this report, with almost half of its servicemen at some time debilitated by venereal disease. The army could not ignore such evidence. The town’s response was to open a small foul ward at the Union infirmary to provide medical treatment for the women afflicted with syphilis (as detailed in Chapter 6), but pressure for action to control prostitution continued to build. As we shall see in Chapter 9, it was shortly after this army report was released that the garrison commander banned women from the barrack huts and made a direct request to Colchester’s magistrates for certain beerhouses reckoned to be responsible for the outbreak of venereal disease to be shut down.12 But when the army did attempt to sort the problem out through the CDAs, which removed diseased prostitutes from the streets for several weeks at a time, some viewed it as the introduction of licensed prostitution.

The army and the garrison made sporadic attempts to divert soldiers into healthier activities and to discourage their off-duty roaming. In 1862 a magic lantern was employed to illustrate the camp schoolmaster’s lectures on rather predictable subjects. The instructions for how to operate the magic lantern included limiting the lecture to one hour and making it ‘as interesting as possible’.13 In 1863, when the activities of the Army Scripture Readers’ Society were reported, their Wesleyan Reader was employed in ‘reading, advising and praying with soldiers and their families’. This Society attempted to instil in the soldier middle-class values he might not previously have encountered: ‘all those benign influences … viz the domestic hearth, the family altar, the blessing implored upon our food and that negative though powerful motive to abstain from vice – the dread of blushing before our own family …’.14

In 1864 the camp decided to provide soldiers’ recreation rooms, one for each battalion, containing ‘harmless’ games, books and newspapers, and nine acres were set aside for soldiers to use as allotment gardens. In 1865 a military gymnasium was built. But these limited recreational facilities for off-duty soldiers could not compete with alternative le...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- List of abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Colchester’s Victorian garrison

- 2 The life of the prostitute, cradle to grave

- 3 Hannah Murrells and Thomas Platford

- 4 Men who encouraged prostitution

- 5 The Lifeboat and The Anchor

- 6 The Contagious Diseases Acts and the lock hospital

- 7 Policing prostitution

- 8 The role of Colchester’s solicitors

- 9 Adjudicating prostitution

- 10 The Ship at Headgate

- 11 Reformers and neighbours

- Conclusion

- Bibliography