![]()

3 Designing a Career Part I:The Animation Artists

“I feel like I’m at a point in my life where the decisions I make now are going to determine my future career. Ultimately, I hope to create a body of really memorable works of animation, something that will hopefully inspire others or future animated films.”

—Chris Conforti, Animator

Iwould define a career as something you don’t put off to think about tomorrow, but rather actively build up slowly each day. Careers are the progression of someone’s working life or professional achievements. While careers imply careful planning and a disciplined focus of energy, there’s some degree of chance involved as well.

Opportunities happen seemingly by chance, but only those who have made themselves ready can take advantage of an opportunity wherever and whenever it may strike. Even the smallest of opportunities grow a career like a snowball rolling down a snowbank.

The function of this chapter is to flesh out (in the most realistic manner possible) the professional life of an animation artist. Find out what happens when art meets commerce. The experts are waiting for us below. Grab a snack. Hunker down and read on.

CAREER PATHS: STORYBOARD ARTIST

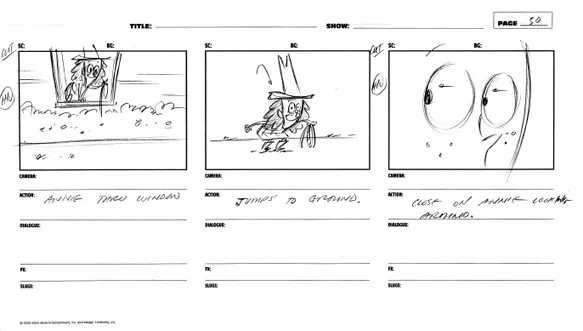

The storyboard is the visual shot-by-shot translation of a script and is the basis for the entire production process that follows, including design, background and layout, animation, and postproduction. Despite changing technology, storyboards are still mostly drawn by hand, although sometimes they’re drawn directly into a computer program such as Flash, where the storyboard panels can be easily assimilated into an animatic.

Storyboards represent the finished product long before great time and expense goes into a project. The storyboard artist, working in the style of the production, maintains storytelling continuity, breaks down the script into scenes or shots, establishes the size relationships between characters and props, and indicates the acting by hitting strong poses on each story point. In addition, the storyboard artist is often the first to rough out new background locations, characters, and props. A storyboard artist balances strong drawing skills with a good knowledge of anatomy, acting, directing, staging, and the ability to think creatively and quickly. With such commanding skills, storyboard artists often develop into animation directors.

Veteran storyboard artist and co-creator of Frederator/Nickelodeon’s Call Me Bessie!, Diane Kredensor, describes the daily duties of a storyboard artist. “First, you go through the script and thumbnail out your shots. Then you pitch your thumbnails to the storyboard supervisor or animation director for notes and changes. From there, you flesh it out, adding the acting, into a full rough storyboard. Some productions already have the voices recorded, and the board artist will board to track. Otherwise, you create (draw) the acting and the voice actors match your board. Once your rough board is approved by the director, you make it pretty, putting everything on model, and then you’re done (and ready for the next script!).”

Scott Cooper, who has storyboarded on such projects as Blue’s Clues, Maya and Miguel, and Clifford’s Puppy Days, says that a storyboard for a half-hour TV episode usually needs to be completed in three weeks. “After my thumbnail sketches get approved, I try to board about a script page a day.” Storyboard artists Liz Rathke (Smurfs, Brand Spankin’New Doug, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and Pinky Dinky Doo) and Dev Ramsaran (The Super Mario Brothers Super Show and Stanley) agree on the importance of assigning yourself a daily page count. Ramsaran adds, “That way you’re not wondering at 3:00 A.M. why you are on page three of the script instead of page nine.”

What kind of training and skills does a storyboard artist need to develop to start out and to keep advancing in her career? According to Diane Kredensor, you want to be a good draftsman, able to draw the human figure in a variety of poses “Other skills should include strong storytelling, cinematography, staging, and composition. Storyboards should clearly communicate ideas to the entire production team, so strong communication skills are an important asset.”

Kredensor never went to art school, but she knows a lot of excellent artists who have gone to Cal Arts and NYU. Her best advice: “Take any classes you can find on storyboarding, and look for a mentor, someone whose work you admire, and just start boarding as much as possible and use their feedback to keep learning and improving. If you can land a job doing storyboard revisions, it’s a great way to immerse yourself in it and get paid at the same time.”

Like Kredensor, Liz Rathke didn’t go to art school, but she did watch a lot of Bugs Bunny cartoons growing up. “I would watch them frame-by-frame. I studied the comic timing, which is surprisingly important even in storyboards; but even more importantly, the composition, and what makes good action. You have to have a vivid imagination for images that move and be able to capture the essence on paper.”

Rathke started out as a storyboard revisionist doing corrections on story-boards that were done by seasoned, talented artists. “I worked with producers; they would each explain why certain things had to be done certain ways. It made it easy for me to eventually go off on my own, knowing the rules of animation.”

All the experts agree that the most intensive learning takes place on the job. Dev Ramsaran explains, “The more experience you have out there working with other people’s good boards, the better your own boards become. In fact, you will even learn what not to do by working with bad boards.”

Speaking of good boards, what should a storyboard artist include in her portfolio? For Diane Kredensor, the answer is variety. “I believe a wide variety of styles and shows make a strong portfolio; from action adventure, to comedy, to preschool. When I look at portfolios to hire potential board artists, I like to know that they can adapt to any style.”

Scott Cooper advises showing only your best work. “You can always show additional work in an interview.” Cooper adds, “Sequential art like comic books or newspaper strips are good to show as well. Also have some life drawings (both human and animal).”

For those just starting out, with no professional board samples available, Cooper recommends you write a script or find a script sample on the Web and simply board it out.

Career Advice

Diane Kredensor notes that while learning to board in Flash is now a great asset, you still need to know basic cinematography and storytelling, which will always be the same. For those starting out, Kredensor advises, “The best way to learn is by doing it, then ask your teacher/mentor/co-worker what’s missing that would make your work stronger, and put it in. Animation is a team effort, and I believe the best shows come from a group of people who are willing to put their egos aside.”

Scott Cooper adds, “Storyboarding requires you to work quickly, be able to take direction, and then make a lot of changes to your drawings. You can’t get too precious about your work.”

Dev Ramsaran stresses the importance of doing your own work, outside of studio assignments. “Sometimes your creativity can feel stifled even when working on some beautiful productions, because you’ve had no say in the initial designs or story. I have been working on a four-minute independent film for the past five years, whenever there is a spare moment. It is fantastic therapy for one’s stifled creativity.”

The Storyboard Artist’s Bookshelf

Recommended reading list:

♦ Film Directing Shot by Shot by Steven Katz, Butterworth-Heinemann (1991)

♦ The Five C’s of Cinematography: Motion Picture Filming Techniques by Joseph V. Mascelli, Silman-James Press (1998)

♦ Paper Dreams: The Art and Artists of Disney Storyboards by John Canemaker, Hyperion Books (1999)

♦ Don Bluth’s The Art of Storyboard, DH Press (2004)

♦ Animation: The Whole Story by Howard Beckerman, Allworth Press (2003)

♦ Inspired 3D Short Film Production by Jeremy Cantor and Pepe Valencia, Premier Press (2004)

CAREER PATHS: ANIMATION DESIGNER

Animation history books pinpoint a time in the 1950s when designers began to dominate the industry. The results changed the look of animation on the screen, TV, and even on Madison Avenue. Animation was pulled away from its comic strip and storybook illustration roots and brought into the modern age, where the new influences might be cubism, abstraction, and surrealism. Animation designers not only create the final look of what you see on the screen, but also provide inspirational and conceptual art to sell shows.

What does an animation designer do? If we were to stalk one for a day, what would we learn? Animation designer Dagan Moriarty (Leader Dog, Tortellini Western) answers, “The main job is to design and draw within the visual parameters of the specific show or film and to have fun with it! A good designer will push to make the project as visually strong and appealing as possible. It’s our job to stay inspired, and to some degree, to keep the whole crew inspired. It’s our designs that everybody must work with day in and day out. An animation designer helps things stay visually coherent, too, usually working closely with the Art Director.”

Moriarty continues, “Design is usually a very collaborative step in the animation process. Most of the time there will be a design team, however small or large, working together on a show.” Veteran designer Teddy Newton (The Incredibles) agrees: “I’ve often sat with other artists when creating a character. I love to bounce off of other artists such as Tony Facile and Ricky Neirva.”

Most importantly, Moriarty reminds, “You are designing for ’animation.’ How well will your designs work in motion? You train yourself to think that way.”

What kind of training and skills does an animation designer need to develop starting out and also to keep advancing in his career? Animation designer Alex Kirwin (My Life as a Teenage Robot) believes versatility is important. “You have to know how to be just as expressive in a pre-existing drawing style as you are in your own, or you have to know how to invent a brand new set of stylistic sensibilities to best suit a new project. If a desire to take apart household objects to understand why they function designates a future engineer, then the same has to be true of almost any type of designer. You have to want to examine all sorts of art, graphics, and drawings, and break them down into their components to find out what makes them tick.”

Animation designer Ian Chernichaw {Blue’s Clues) answers that all animation designers have one thing in common: a thorough understanding of the animation process. “Animation designers need to know the current technologies, trends, computer software, and programs. You should also know how to animate because you will often have to supply animators with angles, positions, and turnarounds, and will be expected to be familiar with animation lingo.”

Debra Solomon, who created the design of the animated Lizzie McGuire, thinks an animation designer should be able to create characters that feel real to the viewer and can emote. Solomon adds, “Drawing skills are important but some acting ability is good, too.”

Now how do you best show off your animation design skills in a portfolio? Alex Kirwin talk...