- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Through her own story of loss and spiritual seeking, paired with mandala meditations and rituals, bestselling author of Feeding Your Demons Lama Tsultrium Allione teaches you how to embody the enlightened, fierce power of the sacred feminine—the tantric dakinis.

Ordained as one of the first Western Buddhist nuns and recognized as a reincarnation of a renowned eleventh century Tibetan yogini, Lama Tsultrim nonetheless yearned to become a mother, ultimately renouncing her vows so she could marry and have children. When she subsequently lost a child to SIDS, she found courage again in female Buddhist role models, and discovered a way to transform her pain into a path forward. Through Lama Tsultrim’s story of loss and spiritual seeking, paired with her many years of expertise in mandala meditation, you will learn how to strengthen yourself by following this experiential journey to Tantric Buddhist practice.

The mandala was developed as a tool for spiritual transformation, and as you harness its power, it can serve as a guide to wholeness. With knowledge of the mandala of the five dakinis (female Buddhist deities who embody wisdom), you’ll understand how to embrace the distinct energies of your own nature.

In Wisdom Rising, Lama Tsultrim shares from a deep trove of personal experiences as well as decades of sacred knowledge to invite you to explore an ancient yet accessible path to the ability to shift your emotional challenges into empowerment. Her unique perspective on female strength and enlightenment will guide you as you restore your inner spirit, leading you toward the change you aspire to create in the world.

Ordained as one of the first Western Buddhist nuns and recognized as a reincarnation of a renowned eleventh century Tibetan yogini, Lama Tsultrim nonetheless yearned to become a mother, ultimately renouncing her vows so she could marry and have children. When she subsequently lost a child to SIDS, she found courage again in female Buddhist role models, and discovered a way to transform her pain into a path forward. Through Lama Tsultrim’s story of loss and spiritual seeking, paired with her many years of expertise in mandala meditation, you will learn how to strengthen yourself by following this experiential journey to Tantric Buddhist practice.

The mandala was developed as a tool for spiritual transformation, and as you harness its power, it can serve as a guide to wholeness. With knowledge of the mandala of the five dakinis (female Buddhist deities who embody wisdom), you’ll understand how to embrace the distinct energies of your own nature.

In Wisdom Rising, Lama Tsultrim shares from a deep trove of personal experiences as well as decades of sacred knowledge to invite you to explore an ancient yet accessible path to the ability to shift your emotional challenges into empowerment. Her unique perspective on female strength and enlightenment will guide you as you restore your inner spirit, leading you toward the change you aspire to create in the world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Wisdom Rising by Lama Tsultrim Allione in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Buddhism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

BuddhismPART 1

Meeting the Mandala

1

MY JOURNEY TO WHOLENESS

God is an infinite sphere, the center of which is everywhere and the circumference nowhere.

—LIBER XXIV PHILOSOPHORUM

When I was a teenager, I liked to wander around Harvard Square, where students and professors rushed across the bustling traffic on their way to classes. At that time it was a neighborhood center with bookstores, a grocery store, a hardware store, a deli with huge hot pastrami sandwiches on sourdough rolls, a restaurant to which my grandfather walked every day to eat fresh fish, and an ice cream parlor that had the best peppermint ice cream with little red peppermint candies melting in it.

My maternal grandfather had long since retired from teaching philosophy and business at Harvard, but he continued to live with my grandmother, a fellow philosopher and also a former professor, in a small white house in Cambridge at 8 Willard Street. I visited them on weekends from my boarding school on the outskirts of Boston, a great getaway from dorm life to their eccentric little house with uneven colonial wide-board wood floors, and the Greek vases he collected perched precariously on a rickety table in the small, dark living room.

During one of my visits, when I was a senior in high school, I was wandering in the book section of the Harvard Coop when I came upon a big hardcover volume called Man and His Symbols edited by Dr. Carl G. Jung. It had numerous illustrations and photographs, and it was unlike any book I had ever seen. A Tibetan mandala graced the cover, and there were many more mandala images within the book. I was so magnetized by the mandalas that I immediately bought it.

I took it back to my grandparents’ house, went up to my small guest bedroom, and leaned back on the pillows on the old horsehair mattress, opening the book to find Tibetan mandalas and all the other representations of mandalas from various cultures around the world. Looking at a Tibetan mandala, I held my gaze steady, concentrating on the mandala’s center. A luminous dimension opened up. I felt a deep stillness within me. No piece of art had ever triggered such a powerful experience. I had an eerie feeling of familiarity combined with fascination about what had happened to me and what these paintings were. Throughout the next years, I carried the book everywhere with me and contemplated the mandalas.

In the book, Dr. Jung introduced the mandala in many forms, not only traditional Tibetan, but also the mandalas in architecture, city planning, Christian art, stained-glass windows, tribal art, and indigenous ceremonies. But I was particularly drawn to the Tibetan mandalas: their depth and intricate symmetry resonated and called to me. I sensed they were not mere paintings. They emanated a mystical energy that made me wonder what truths lay within them. Their power was derived not from cognitively knowing their meaning, as I do now, but from direct contemplation of the mandalas themselves. It was this first encounter with Tibetan mandalas that became the catalyst for my budding spiritual search.

I was inwardly drawn to Buddhist culture, particularly toward Tibet, but had few resources available in New England. It was a time before the Internet, Google, Facebook, and YouTube; communication took place only via telephone and snail mail. To find something out, you had to read a book, speak to someone knowledgeable, or go to the source yourself. I read about Tibet in my parents’ encyclopedia, but other than that couldn’t find any books on the subject. Around this time my maternal grandmother gave me Zen Telegrams by Paul Reps, a book of Zen haiku and calligraphy. The short poems combined with brushstroke paintings inspired what I would now call my first meditation experience, an insight into an “awareness of awareness,” or what I called at the time “consciousness of being conscious.”

I was at our summerhouse on a lake in New Hampshire. I had been reading Reps’s book in my upstairs bedroom, a rustic space with unfinished pine board walls and open beams. I decided to crawl out the window in my sister’s bedroom and sit on the porch roof. In front of the house were four towering white pine trees. A soft breeze was blowing from the lake as I sat in silence. Then I heard pine needles falling on the roof, a barely perceptible sound. At that moment, I was aware of my consciousness, and simultaneously I experienced the gentle breeze and falling pine needles on the roof. I did not fully understand what I experienced; I had no context, no spiritual teacher, and it was nothing my friends would have understood, yet it was something I would never forget, a profound sense of awareness and peace.

These early experiences and others inspired me to become a spiritual seeker, and this longing came to dominate my life. After I graduated from high school, I went west to the University of Colorado, but I found nothing in school that provided me with the inner wisdom I was seeking. Then one day in the autumn of my sophomore year, while meandering through the stacks in the university library, I spotted a book that drew my attention. It was one of the first books published in English about yoga, The Hidden Teaching Beyond Yoga by Paul Brunton. I quickly checked it out and brought it back to my dorm room.

After reading it for a while, I grew sleepy and then put the book down and turned onto my stomach to take a nap. As I lay there, I had the sensation that my body was being lifted off the bed, and I was floating up above it at the level of the ceiling. My experience was that this was actually happening. It was so real, and it terrified me to be floating, I forced myself to open my eyes, finding myself back on the bed. This out-of-body experience intensified my spiritual search, and I talked about it with my best friend, Vicki Hitchcock, whose father was at the time the American consul general of Kolkata. Upon meeting during our freshman year, we’d recognized each other as kindred souls, and constantly shared our search and interests in “the mystic East” as we called it. In fact, we have remained friends throughout our lives, and have both ended up following the Tibetan path since we were nineteen.

Our search heated up in the summer of 1967, the Summer of Love. We both dropped out of the University of Colorado and traveled together to India and Nepal. We flew to Hong Kong, where we found an esoteric bookshop and bought every book they had about Tibet. We then took turns reading them as we sailed on an Italian ship to Bombay and then flew to Kolkata, where Vicki’s parents were living in a large, old colonial house next to the US consulate. After working for some time in Mother Teresa’s home for unwed mothers and abandoned babies, Vicki and I made our way to Nepal.

Lama Tsultrim before leaving India, 1967.

SWAYAMBHU

One morning, while visiting a Nepalese family in the center of Kathmandu, we were invited up to the rooftop of their house to see the view. The valley was covered in low-lying fog, but in the distance were the crystalline peaks of the Himalayas; much closer, about a mile away, like an ephemeral palace on an island floating in a lake, was a glowing white dome topped with a sparkling golden spire. It was one of the most mystical sights I had ever seen, and when I inquired about it, I was told it was called Swayambhu, also known as the Monkey Temple because a troop of wild monkeys lived on the hill, and it was one of the most sacred places in the city.

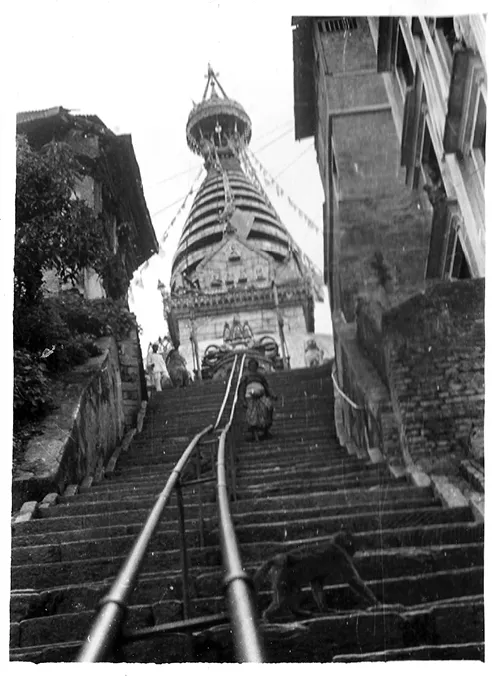

A few days later, we had the opportunity to join a predawn procession that was going up to this hill. Walking through the darkened streets of Kathmandu was like being whisked back to medieval times. There were pigs, dogs, and cows everywhere, scavenging for the garbage people threw into the streets—a medieval garbage collection service!

We walked through the valley, crossing the river on an old bridge that led to a narrow dirt path between rice paddies, and then gradually made our way up the hill. The path became steeper and steeper, and finally became a staircase going straight up. The morning light began to illuminate our surroundings just as we emerged at the top of the stairs.

Stairs leading up to Swayambhu stupa, Kathmandu, Nepal, 1967.

Before me stood the white dome, its round golden spire soaring about three stories tall. On the spire’s square base were mysterious painted Buddha eyes looking out in the four directions—north, east, west, and south. I later learned that this was an ancient stupa (Buddhist shrine) representing the mandala, which is the basic structure of the cosmos in the Tantric Buddhist tradition—the circular architecture of the centered enlightened experience, a cosmological representation of the universe. Swayambhu means “self-manifested,” because it was said to have been an island in the middle of the lake that was once Kathmandu Valley, and on that island there was a self-existing flame over which the stupa was built.

Swayambhu stupa in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal.

For a nineteen-year-old American girl to encounter this incredible structure, one of the most holy sites in Nepal, in the golden light of dawn was pure magic. Gradually I could see more and more as the sun rose. I began to circumambulate the stupa clockwise, following the Nepalese pilgrims. I saw that at the base in the four directions were five niches with Buddha statues, one in each direction—except for the east, where there are two, one of which represents the center—and they each had different hand gestures, or mudras. As I walked around, smelling the pungent Nepalese rope incense and hearing the huge bells ring, I experienced an incredible sensation of familiarity and remembering.

As I sat there that morning, on top of Swayambhu looking out over the valley, I felt that my life had been altered—and as it turned out, it had been. Here is something I wrote about my first encounter with the Swayambhu stupa in 1967. It was the first stupa I had ever seen, and of course, I had no idea at that time that I would return to live there and became a nun.

We were breathless and sweating as we stumbled up the last steep steps and practically fell upon the biggest vajra (thunderbolt scepter) that I have ever seen. Behind this vajra was the vast, round, white dome of the stupa, like a full solid skirt, at the top of which were two giant Buddha eyes wisely looking out over the peaceful valley which was just beginning to come alive.14

It became a place I went every morning, sitting in a corner of the monastery at the top of the hill next to the stupa. After a few days, a little carpet appeared in my corner; after a few more days, I was served tea when the monks had their tea during their morning meditation practice. It became my place, my monastery—the outer mandala that I would refer to inwardly for the rest of my life.

Lama Tsultrim in Dharamsala for the first time, in 1967, looking a little dusty. She hadn’t bathed for three weeks, it was too cold.

Lama Tsultrim with Tibetan woman who dressed her up in Tibetan clothes, Dharamsala, India, 1967.

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE AND SAMYE LING

I returned home and went back to college in Vermont, because my parents wanted me to complete college. But all I could think about was going back to the Tibetans in India and Nepal. So after another year in college, I got enough money together for a cheap ticket to Europe. I went first to Amsterdam, where I heard about a Tibetan monastery in Dumfriesshire, Scotland, called Samye Ling, the first Tibetan monastery in the West. I left Holland the next day, took the ferry to England, and hitchhiked to Scotland straight from the docks.

The very day I arrived, as I was coming down the main staircase of the old Scottish country house that was the seat of Samye Ling (before they built their big monastery), I saw a young Tibetan man in a purple Western-style shirt struggling up the stairs accompanied by young Westerners, several men and a large woman, who were treating him with great deference. I stepped aside, but not before our eyes met and he smiled at me and said, “Well, hello!” in a high-pitched, slightly slurred voice.

It turned out this was the preeminent and unconventional Buddhist teacher, the wild, young, Oxford-educated Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, and that day he was returning from a long stay in the hospital recovering from a serious car accident. The accident had occurred when he was driving drunk with his girlfriend. Coming to a fork in the road, he couldn’t decide whether to go home with her or go back to the monastery, so instead they barreled straight into a joke shop. The accident left him hospitalized for more than a year, and he remained partially paralyzed on his left side; it also led him to formally decide to disrobe. He had not been keeping his monastic vows for some time, so he decided to let this façade go and no longer depend upon the monk’s guise to make his way in the Western world.

I ended up spending six months at Samye Ling. I met Trungpa Rinpoche several times during my stay and read what were then his only books: his biography, Born in Tibet, and the recently released Meditation in Action.

The first time I heard the word dakini was at Samye Ling. Trungpa Rinpoche had various girlfriends, and my friend Ted, a Scottish rascal with a mo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Author’s Note

- Introduction

- Part 1: Meeting the Mandala

- Part 2: Meeting the Dakini

- Part 3: Meeting the Five Families and Wisdom Dakinis

- Part 4: Wisdom Rising: Practices

- Conclusion

- Photographs

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Appendix A: Abbreviated Mandala of the Five Dakinis

- Appendix B: The Attributes of the Five Buddha Families

- Additional Resources

- Recommended Reading

- Glossary

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Permissions

- Copyright