![]()

PART I

![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE END OF AN ERA

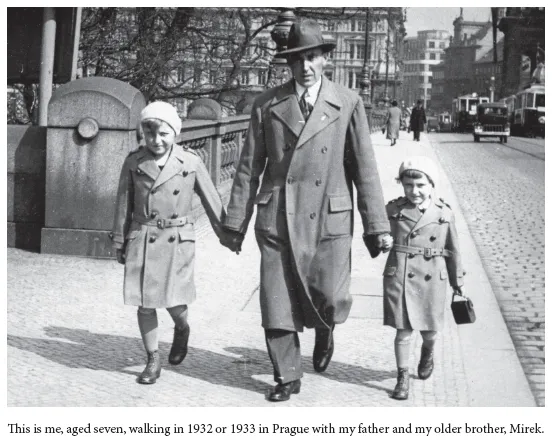

Whenever I think of my childhood, my mind always comes up with the walks with my father.

There were a good many things wrong with Dad. He had an explosive streak and sometimes furiously shouted at Mother. I gathered from their nasty quarrels that, especially during the war, he was not a good provider. Dad also had a penchant for borrowing money with the greatest abandon and without equal propensity for paying back. He claimed that being pursued by creditors was fun: “As long as they expect to get their money back,” he once told me, “they wave to me and shout ‘Hi!’ all the way across the street.” As soon as he settled the debt, he added, “they look the other way.”

There is no question that his failings left a deep mark. For my brother Mirek and me, the fierce exchanges between Mother’s tears and Dad’s angry voice were a nightmare, and the hounding creditors were a source of profound embarrassment. To this day, I recoil from emotional arguments, and I buy everything in cash.

But Dad also tried to be a good father in the old-fashioned sense, as a moral guide to his two children. I don’t mean an arm’s-length elder adviser, the way I was to my own sons, Jan and Ben, in my studious effort to avoid any suggestion of value imposition. My Dad’s attitude was the exact opposite. He was eager to tell Mirek and me what we should believe and think, and the way he went about it was anything but subtle.

When I was about six or seven years old, he would take me for walks. Not in Vršovice, the humdrum, middle-class periphery of Prague where we lived and where there wasn’t any cluster of trees worthy to be called a park, any impressive bit of architecture, or a store window with anything exciting to look at. Dad, whose aspirations always exceeded his reach, would put on one of his natty suits and a homburg hat that made him look like an affluent lawyer, and he would take me to the center of Prague where the broad sidewalks were lined with leafy linden trees, and brightly lit stores displayed luxuries like grapefruits and canned pineapples.

We’d take one of the rattling, ubiquitous streetcars that roamed the Prague streets like an army of ants and we’d ride all the way to the Wenceslas Square, the very heart of the city. The so-called square is actually Prague’s version of the Champs Elysées, a boulevard dominated by a huge equestrian statue of St. Wenceslas, a not particularly distinguished tenth-century Czech king. The boulevard slopes down toward the enchanting Old Town and intersects a couple of broad avenues that in those pre–World War II years were full of theaters and bustling cafés.

Dad and I would get off the tram at the top of the square and slowly head for the Old Town. For me, our incursion into the world of affluence was full of thrills. On both sides of the wide boulevard, well-dressed crowds streamed in and out of big stores and movie houses. Posh cars glided past traffic policemen waving their arms. From the square’s numerous sidewalk kiosks wafted the mouth-watering aroma of boiled “párky,” the elite of world’s hot dogs. (Párky, whose subtlety is unmatched anywhere outside the Czech provinces and Austria, are a cultural and historical phenomena. Bohemia and Moravia, once an independent kingdom, lost a crucial battle in 1618 and for the next three hundred years became a part of the Austrian realm. The shared mastery of making párky was one of the rare happy results of that shotgun union.)

Dad would hold me by the hand, we’d walk, and he’d talk. He’d talk a lot about Prague, which he loved with a passion known only to natives of very old and very proud European cities. It was a place he knew intimately—every alley, every hidden courtyard behind an unlocked door, every chubby angel perched above a stone water fountain, and many of its roofs and chimneys. Those heights of the town he got to know the hard way, while eking a living as a chimney sweep, a part of his life he hated and tried to hide. But even that humble work added to his bond with Prague. The city was so important to his self-esteem and identity he never spoke about it with his customary irreverence.

By the time we reached the Old Town, Dad would break away from his cherished topic and address the subject of values. As one would expect from a practiced storyteller, his lectures were delivered with flair and dressed up in overstatement, but they always had a valid point.

Unlike many people of his background, Dad had a great respect for higher education, and he would have been elated if Mirek or I had ever earned a doctorate. Upward mobility was one of his hallmarks. An only child, he was taken out of school at an early age after the death of his father, who was a tailor of all-leather work clothes. To provide for himself and his mother, Dad was apprenticed to a chimney sweep, but he never accepted the job’s lowly social standing.

After 1918, when the Habsburg empire disintegrated and the Czechs and Slovaks won independence, Dad quickly recognized the status value of a well-pressed military uniform. He joined the new Czechoslovak army and, being bright, witty, and personable, he rose from a private to battery commander in a horse-drawn artillery regiment.

Although he could never afford to satisfy his taste for fine clothes and better things in life, Dad was not envious of people who were more fortunate. But there were three types of individuals my father despised, and whose iniquities he described on our walks with passion. Collectively, he called them “people with no class.”

One prominent group in Dad’s low-life trifecta were people pretending to excellence by affecting intellectual polish. “Poseurs”—posturing phonies—who put on airs were the worst liars, Dad charged, because they didn’t just brag about a thing or two (as he would do), but their whole life was a lie. “With a poseur you never know who he is, Milan,” Dad would say, “because he himself doesn’t know it, either.” The most satisfying punishment that Dad could wish for a poseur was to be found out and held up to public opprobrium, and the more ego-crunching the discovery, the better.

Dad’s second category of people unworthy of our planet was sviňe (swine). The term covered a mixed bag of unsavory characters, ranging from loan sharks who preyed on orphans and widows to monstrous tyrants like Adolf Hitler. Hitler, by the mid-1930s, was not an abstract term for a Czech schoolboy. I was not quite six years old when der Fűhrer took power in the neighboring Germany, and he very quickly entered my horizon as a dreadful symbol of utmost malevolence and evil. The Czechs had a long history of resisting cultural subjugation by the Austrian monarchy, and the rise of expansionist Nazism across the long Czech-German border was the subject of frequent and worried comments both at home and in school.

The third and numerically largest group in Dad’s unworthy menagerie was póvl (rabble), a label he applied to people who were not only ignorant and crude but also indolent and hostile to anyone who achieved more in life. Absence of worldly goods was not what Dad had in mind when he heaped disdain on póvl—it was a meanness of spirit. Avoiding the rabble was the highest injunction that Dad wanted to impress on his sons. One had to be alert to the menace of the poseurs and the swine, but above all, one had to put inexorable distance between oneself and the slothful, mean-minded, pestilential póvl.

I still see him, stopping in the middle of the sidewalk, raising his arm above his head like a priest invoking God’s righteous wrath, and exclaiming loudly enough to startle the passersby:

“Beware of the poseurs, the swine, and the rabble, Milan!”

The performance was addressed to me as well as to anyone who happened to be within earshot, and Dad’s face would light up with delight if he caught the attention of some pedestrian.

In later years, I sometimes wondered how this restless man, full of loud cheer and bonhomie, who bridled against routine and the ordinary, felt about the placid world he had entered in the early 1920s when he married my mother. My mother, the youngest of eleven children in a patrician family, was humorless and withdrawn. We lived in a stolid, turn-of-the-century walkup apartment building that housed most members of my mother’s clan. My father fit in like a fox in a chicken coop.

The family that he joined had an undisputed matriarch in my maternal grandmother, Marie Simandlová. Slender and erect, she was the widow of a well-remembered local baker and, in the eyes of our family and neighbors, the first lady of the neighborhood. To go shopping with Grandmother was to bask in her reflected glory. As she strode down the main street, which was just a few steps from our house, merchants outside their stores and strolling burghers would shower her with ornate courtesies. Their greetings, a remnant of the era of Habsburgs, ranged from a courtly “My humble bow!” to an elaborate “I kiss your hand, my gracious lady!” Striding proudly by Grandma’s side, I’d get approving pats on the head and, frequently, a piece of candy.

Much of the rest of the house exuded the same ancien régime atmosphere. The ground floor of our apartment house was occupied by my mother’s eldest sister, a kindly, always smiling woman who was just as slim as Grandmother. Her husband, Uncle Ludvík, was shaped like a Tweedledum and used to be a well-known Kapellmeister (a band conductor) in the Imperial and Royal Austro-Hungarian Army. His career ended in 1918 when the empire fell apart and royalty went out of fashion. Uncle Ludvík’s lustrous past was captured in his near-life-size, hand-colored photograph in a gilded ornamental frame that dominated the Ludvíks’ living room. It showed him with a waxed, upward-sweeping handlebar mustache, a shiny pince-nez, and a splendid gold-braided blue dress uniform topped by a broad sash and an array of medals. It was his gala attire he wore when playing at the annual Opera Ball in Vienna, attended by leading members of the Imperial and Royal family and court.

If Uncle Ludvík’s world fell apart with the demise of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, he never complained about it. Instead, he conducted Czech orchestras at considerably less prestigious events than used to be his realm and took up carpet weaving to boost his meager income. I remember him best, toiling at the loom while softly humming military marches and melodies from Léhar and Strauss.

On the floor above the Ludvíks lived the family of my mother’s eldest brother. Uncle Simandl was the director of Vršovice’s major bank, and he looked the part: he was a tall, husky man with heavy eyebrows and a commanding voice and manner. He died when I was very small. His widow was a neat, calm, always pleasant and well-dressed woman. My brother and I called her “Teta Lepší” (Aunt Better) because everything she baked or cooked tasted better than what we had at home. Aunt Better’s life was dedicated to the welfare of her son, Milda, and her two daughters.

One of them, Cousin Božena, conceived of the unheard-of notion of following in her father’s footsteps and making a bank career instead of getting married and raising children. Under intense pressure from the whole clan, Božena eventually gave in and announced that she’d get married. The whole family celebrated except for my father, who had argued all along that Božena should be left alone. When it turned out that my cousin’s fiancé was a printer, a “mere” blue-collar worker, the building almost audibly gasped in horror.

The family citadel had another tenant who did not meet with universal approbation. Uncle Bořik was an avid soccer fan, promoter of a lowbrow amateur theater group, and a supporter of oddball politicians. Worst of all, he had divorced his first wife whom everybody liked, and married an actress who dyed her hair and spent a lot of time at the hairdresser. Mirek and I were very fond of Uncle Bořik. He was generous to a fault and loved children though he had none of his own.

But however likable, on the family prestige ladder Uncle Bořik stood as low as my father, the irreverent outsider. Dad and Uncle Bořik should have been natural allies, but they profoundly disagreed on Czech politics. Dad was a great admirer of Czechoslovak president Edward Beneš, one of the founders of the republic and a highly respected leader of the League of Nations, but Uncle Bořik considered Beneš a wimp.

Except for Grandma Simandlová whom he liked, Dad found the family stifling, and he liked to complain that “there should be a law” against more than two relatives living in the same apartment building. That was Dad’s point of view; Mirek’s and mine was just the opposite. For us, the close family ties meant security and the warmth of home. Mirek was everybody’s favorite. He was tall for his age, strikingly handsome, and had the gentle disposition of Uncle Bořik. I was more in my father’s mold, but because I was Grandma Simandlová’s youngest grandchild, I was much forgiven. Mirek and I had the run of the house, and we loved the serene years of our childhood.

One of the basic verities to which the Czechs subscribed during my childhood (and which rhymes in the Czech) asserted that “hard work—and striving—is our salvation.” As little kids we were taught to take pride in the Czechoslovak democracy, which the republic’s founder, President Thomáš Masaryk, consciously shaped on the model of the United States. Czechoslovakia was portrayed to us, not unrealistically, as a small but upright and worthy member of the community of nations.

This antebellum bliss lasted until I was almost ten years old and Hitler felt strong enough to start conquering the world. The possibility of a German aggression had been hanging in the air for years, but my first distinct sense of impending war came from a conversation between my father and two of his fellow army officers that I overheard in the fall of 1937.

They talked about Hitler’s growing territorial demands on Czechoslovakia and about the scant chances of the Czech army against the mighty Wehrmacht. In the estimate of Dad’s friends, the bombers of the German Luftwaffe were poised to devastate Prague and other major Czech cities from at least three directions. I still remember the grim tone of the conversation, which was unrelieved by the usual jokes and bragging.

Newspaper pictures began showing the rallies of Sudeten Germans supporting Hitler’s crude verbal onslaughts on the Prague government and President Beneš—“Herr Benesh,” as Hitler contemptuously referred to him. An important adjunct to the Nazi psych warfare, thousands of Germans who lived along the Czech border strutted around in the high boots and brown shirts of Hitler’s Sturmabteilungen (SA, storm troops), shrieked “Heim ins Reich!” (Home to the Reich!) and battled Czech cops. The Sudeten Germans were Czechoslovak citizens with full civil rights; their elected representatives sat in the Czech parliament, and German, alongside the Czech and Slovak, was an official language. But in those years of worldwide depression, they had many economic grievances, and more than two-thirds of them voted for a Nazi Party that demanded the annexation of Sudetenland by Hitler’s Germany.

By the summer of 1938, Hitler’s abuse and the Sudeten German antics convinced most Czechs that war was unavoidable. Dad’s unit was mobilized, took up positions close to the German border, and he was hardly ever home. With most of the men away in uniform, women and older people were scrambling to prepare for raids by the dreaded Luftwaffe. Every apartment building, including ours, had to convert part of its basement into a bomb shelter. Uncle Ludvík became an air warden. We children carried gas masks to school, and the whole Prague conducted air raid drills with tear gas.

Even among us small kids, anti-German feelings ran so high I remember a whole flock of us jeering a couple of older women who conversed in the street in German. (Ironically, they were most likely members of the large German-speaking Jewish community in Prague.) The one comforting thought that we all shared and that made the strain bearable was that, if Hitler’s Wehrmacht got on the move, France and the Soviet Union would fulfill their treaty obligations and come to Czechoslovakia’s aid, and Britain would inevitably follow suit.

That naive hope collapsed on September 30, 1938, when a choked-up announcer interrupted the regular program of Radio Prague to read the text of the Munich Agreement. Neville Chamberlain and Edouard Daladier, without as much as consulting Beneš, had handed to Hitler the heavily defended Czech Sudetenland. It was the most shameful political betrayal of the prewar era.

With the stroke of a pen, Chamberlain and Daladier stripped Czechoslovakia of its fortifications facing Germany. France waived its commitment to come to the aid of Czechoslovakia, whereupon Soviet Russia proclaimed void the mutual defense treaty of France, the Soviet Union, and Czechoslovakia. What perhaps hurt most was the message from Munich that in the eyes of the two big Western democracies, the fate of Czechoslovakia did not matter. It was a country, as Chamberlain famously proclaimed upon returning from Munich, “of which we know little.”

I’ll never forget the despair of my father who happened to be at home and was about to return to his unit. As the disastrous news sank in, he placed his head in his hands and cried. He did not say anything, he did not even sit down; he just stood there and cried. It was the only time I saw him so desolate.

A little later I went out with my mother to buy some groceries. It was as if the hurt of the Western betrayal had spilled into the streets and bonded the numbed people of Prague into one shocked family. Total strangers would stop in the middle of the sidewalk to denounce the sellout. Women, including my mother, cried openly while shopping.

The fall and winter that followed were so bleak that in retrospect they seem like a long, sad march into the night. Beneš resigned and went into exile in London. Big chunks of Czechoslovakia were ripped off not only by Hitler but also by the fascist regimes in Hungary and Poland. Dad’s army was dismantled, a new pro-Nazi government took over, and the state-run radio became an outlet for German propaganda. At the end of November Emil Hácha, a sixty-seven-year-old Czech jurist, was made president of what had become a de facto German fiefdom called Czecho-Slovakia. But everybody knew the process that started with Munich was not finished.

The other shoe finally dropped on March 15, 1939, a miserably cold day. Acting on a consent that Hitler personally extracted from the ailing Hácha, the Wehrmacht troops rode into Prague in a snowstorm and stayed for six endless years and one month. The day they pulled in, Dad came to school to walk Mirek and me home because, as he earnestly explained, Mother wanted to “make sure you don’t get into trouble.” As we passed a parked convoy of dark-green Wehrmacht trucks full of surly-looking helmeted troops, Dad ostentatiously spat on the sidewalk in front of a German officer. On that first day of the occupation, the German only scowled.

Two nights later, roaring voices in the street outside our apartment made Mirek and me jump from our beds and run to the window. On the main Vršovice thoroughfare, a few yards from our house, a large crowd of young university students marched under the now-banned Czechoslovak flags shouting in cadence “Němci ven! Němci ven!” (Germans, out! Germans, out!). They were headed toward a former Czech army barracks, which by then had been taken over by the Wehrmacht. The streetlights at our corner had been put out, but we could see in the dark about forty or fifty Czech policemen, waiting. When part of the marchers passed by, the cops charged the demonstration with truncheons, cut it in half, and dispersed it.

As protests go, it was smaller and less violent than I was to see later in the Middle East. The cops sympathized with the students, and the students were not eager to face the German guns down the street. By midnight the neighborhood was quiet, but I could not sleep. My heart was pounding in my throat, my lips were parched, and the shouts of the crowd were ringing in my ears. I was only eleven years old and safely behind the closed windows of the apartment, but I was consumed by a sensation that I had been a part of that street prote...