Chapter 1

Connecting with the West

The Piast Dynasty

Windows onto a Distant Past

Many generations have looked deep into the past for the origins of the Poles and a Polish state—the earlier the better being the working premise. (In this, Poles are no different from the peoples of other nations who as a rule tend to seek an ancient lineage for themselves.) Using the available archaeological and linguistic sources, among others, some scholars have pieced together a neat trajectory—from the prehistoric cave dwellers in the limestone caves of Ojców, through the wooden settlement of Biskupin, existing from circa 750 BC to 550 AD, and in the process moving from hypothetical Proto-Indo-European beginnings to the emergence of Slavic languages and distinct Slavic peoples. They claim that this represents the rise of Poland. For the historian, however, such an approach raises more questions than it answers, especially as quite a parade of peoples had crisscrossed this part of Europe by the end of the first millennium, including Scythians, Celts, Germanic tribes, not to mention Goths, Huns, and Avars. The evidence of life in such ancient times cannot, thus, convincingly be put into “national” boxes.

Not that making sense of traditional historical sources is easy. The historian interested in early medieval Poland must make do with a sparse and fragmented historical record. That Romans never conquered these lands (a good thing) meant that there was no early record of them (a bad thing). Commercial links of some kind clearly connected this part of Central and Eastern Europe with the Roman world—with Roman coins exchanged, perhaps, for precious Baltic amber. Legible signs of the beginnings of what can be called “Poland” are available to us only in tantalizing snippets, however. While the occasional source makes reference to tribes, settlements, or leaders in this part of the world, even these are frustratingly hard to locate on the map in any precise way. So, how are we to deal with the origins of the Poles, and the origin of Poland?

Three Foundational Legends

A different window onto the past is provided by legends. While some may disdain such tales as ahistorical and thus not worthy of our attention, there is much to be learned from these primitive yet enduring attempts to explain the world of the past. As received wisdom, legends also shape the views of new generations. Some of the more interesting legends tell us something about perceptions of relations between peoples—here, between the Poles and their neighbors. The following selection of three foundational legends will provide a working framework for an understanding of Polish history and Polish perceptions.

Consider the legend of three brothers: Lech, Czech, and Rus. Lech was the forerunner of the Poles; Czech, of course, the forerunner of the Czechs; and Rus of the broader Slavic family further east, today’s Belarusians, Ukrainians, and Russians. Each brother decided to set off in a different direction in search of a place to call home. Whereas Czech headed south and Rus traveled east, Lech was led north by a white eagle until he arrived at a tree. From its top branches, Lech took in the view. To the north he spied a mighty ocean, to the east he could see vast fertile plains. Mountains dominated the southern horizon, and dense forests spread out to the west. Was this land not ideal? Enthralled with what he saw, Lech decided to settle right there—indeed, to build a nest of his own. In thanks, he made his emblem the white eagle with outstretched wings.

This legend addresses the larger Slavic family of Central and Eastern Europe and explains how various peoples ended up in their present location. Slavic tribes came to populate much of Central and Eastern Europe around the fifth century. Over time, they became more differentiated, eventually giving rise to more recognizable national groups. The Polish legend speaks of only three brothers, clearly reflecting the local Polish neighborhood. The Poles and Czechs were both members of the western branch of the Slav family, while Rus represented the entirety of the eastern Slav family. Given Lech’s particular location, the southern Slavs (the peoples we associate with the former Yugoslavia) were out of view; they were located to the south of the Czech homeland. The legend likewise hints that the descendants of Czech and Rus were not only the Poles’ closest brothers; we might expect them to figure more prominently within the Polish purview.

The legend also provides some geographical cues regarding Lech’s territory, which was depicted in glowing terms. As we will see, the Polish “nest” founded by Lech was a place called Gniezno, a toponym related to the modern Polish for “nest” (gniazdo). Gniezno, incidentally, is located in the heart of modern Poland. The lands of the Poles are in part described by natural boundaries: the Baltic Sea in the north and the Carpathian Mountains in the south. The western and eastern borders of Lech’s land—those forests and plains—are not as easily delineated, suggesting that such determinations may be more open to adjustment. (It is worth noting that the other Slavic peoples who figured in the legend, the descendants of Czech and Rus, lay to the southwest and east, respectively.) In a nice touch, the legend also provides an ancient justification for a historical detail: the white eagle remains Poland’s emblem to this day.

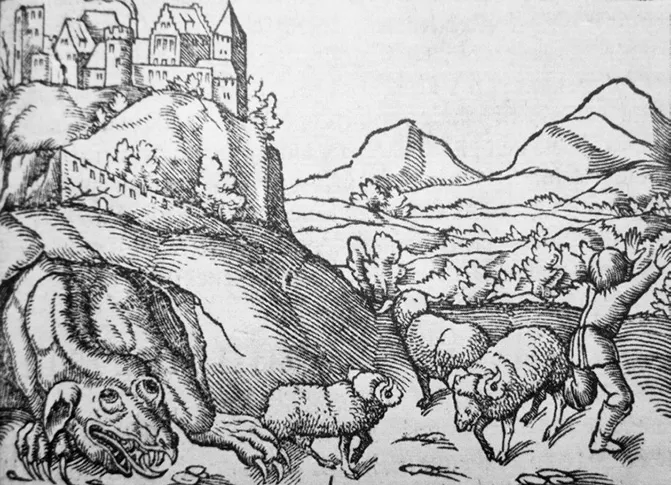

Another legend tells us about the founder of the city of Kraków, a man called Krak. He was a wise villager who, through a clever ruse, managed to kill the dragon that terrorized his people. Krak smeared a sheep with sulfur and cast it into the dragon’s cave; after ingesting this free but unusually spicy meal, the dragon drank from the Vistula (Polish: Wisła) River until he burst. The dragon had lived in the cave beneath Wawel Hill, the future site of the city that long would be Poland’s capital. The legend thus explains both the city’s subsequent rise in importance and the existence of the so-called Krak Mound, a hill on the outskirts of Kraków that was erected in honor of Krak by his thankful subjects. Such mounds, incidentally, were an ancient Slavic way of honoring the dead.

And who can deny the grain of truth in the legend of Wanda, Krak’s daughter, who drowned herself in the Vistula River rather than marry a German who threatened to invade the country if she refused him. Does her tale not suggest the fact, borne out by subsequent history, of a certain long-standing tension in the interactions between Poles and Germans? (For lovers of music, Dvořák’s 1875 opera Vanda is based on this tale, reflecting the Czechs’ own sometimes rocky relations with their German neighbors.) The persistence of the legend of Wanda suggests that Slavic peoples such as Poles and Czechs felt their German neighbor to be a distinct “Other.” Corroboration can be found in the name given by such Slavs to the Germans. The latter were from early days referred to as Niemcy—the mute ones. These Germans were probably not tongue-tied but, rather, spoke an unintelligible (Germanic) language, whereas the Slavic languages were more or less mutually intelligible. Could this be enough reason for a pagan princess to have preferred a different husband? Some versions of the legend interestingly depict the Germans as rather uncouth—let us say barbaric—warriors, in contrast to the more cultured Cracovians. Regardless of the reason for her embracing a watery death, Wanda, like her father Krak, was honored with a mound.

These three legends set the stage for our foray into Polish history. Coming to us out of the mists of time, they hint at the deep prehistoric and pagan beginnings, including the emergence of distinct peoples within the larger Central and East European space. They also provide clues to certain central places and prominent features of the country we will call Poland, as well as evidence that from the very outset Poles have functioned within a world peopled by “brothers” (Slavs) and “others” (Germanic peoples).

Figure 1.1: The Wawel dragon, crawling out of his cave beneath the Wawel Castle, as depicted in a sixteenth-century woodcut. From Sebastian Münster, Cosmografia universalis, Basel, 1544

From Legends to History

Polish history, as opposed to prehistory, dates only from the late tenth century. Prior to this period, various tribes in this general vicinity of Central and Eastern Europe get only the briefest of mention in written sources. A Bavarian geographer in the mid-ninth century enumerated a series of tribes, which appear to have lived in the region. These included the Vuislane-Wiślanie (people of the Vistula River region) and Lendizi-Lędzianie (also in Małopolska, or Lesser Poland, somewhat further to the east); the Glopeani-Goplanie (near Lake Gopło, fed by the Noteć River); the Sleenzane-Ślężanie, Dadosesani-Dziadoszanie, Opolini-Opolanie, and Golensizi-Golęszycy, all in the area of present-day Silesia; and the Prissani-Pyrzyczanie and Velunzani-Wolinianie in the region of Pomerania, on the coast of the Baltic Sea.

An early mention of an emerging threat in the region came from one of the first Slavic states, Greater Moravia, which formed in the vicinity of today’s Czech Republic and Slovakia. Baptized by the missionaries Cyril and Methodius circa 863 AD, Moravians noted the presence of a powerful pagan prince in the region of the Vistula. The reference was likely to a tribe in the region of Kraków, the site not only of the historic mounds already mentioned but also of an enormous cache of ancient metal blades, which suggests that it was a seat of some power, even in this early period. The Vuislane tribe at some point probably came under Czech rule or influence before becoming part of a dynamic state emerging to the north.

Polish Beginnings: The Gniezno “Nest”

The beginnings of Polish statehood emanated from the region of today’s city of Gniezno, part of the region later termed Greater Poland (Wielkopolska). As mentioned earlier, the name “Gniezno” is related to the present-day Polish word for “nest” (gniazdo). The avian metaphor suggests there might be some truth in the legend of Lech. The archaeological record also allows us to see the region’s rise. Given that Lake Gopło is not far from Gniezno, there may well be a relation between the Glopeani mentioned by the Bavarian geographer and the tribe that started a rapid ascendance in the region.

Gniezno had become a stronghold of note, a town where craftsmen settled and trading took place. This nameless people settled along the surrounding rivers and lakes, where they constructed settlements. Around the year 920 AD, the apparent military expansion and buildup of fortified settlements near Gniezno (including Poznań) speak of a significant and speedy expansion; the next half-century would witness further expansion and consolidation in the region as well as beyond. The Gniezno state expanded its influence northward to the seacoast region of Pomerania, although the link was likely loose, and perhaps based on paying tribute. It incorporated territories in the east (Mazovia and Sandomierz) and made inroads into the southeast circa 970; the Lendizi of that last region, however, soon fell under the control of the Rus’ princes to the east.

The dynamic tribe with its seat in Gniezno was only later (around the year 1000) labeled the Polanie—Poles. Etymologically, these are the people of the fields or plains (pole). The sixteenth-century Polish historian Marcin Kromer provided two more hypotheses as to the origins of the name. It could be a contraction of “po Lech” (after Lech), the reference being to the legendary first Pole, or the term could be related to the Poles’ love of hunting (polowanie). Given that Lech’s legendary territory also was rich in forests (and thus probably also in game), any of these explanations could have merit.

The earlier, still prehistorical, period is associated with figures such as the famous Popiel (an evil ruler who, according to legend, was devoured by rats and the ancestors, whether apparent or legendary, of the first Polish ruler of whose name and historical existence we can truly be certain, Mieszko (?–992). Before we turn to him, however, we must decipher the chapter title’s reference to the Piasts. Who were the Piasts, and why were they important?

The Piasts

The first written account of their origins was penned in the early twelfth century by an anonymous monk. He is traditionally called the Anonymous Gaul, as the assumption is that he hailed from France. Scholars more recently have surmised that he spent time at the monastery of Saint-Gilles and was educated somewhere in France or Flanders. The peripatetic monk may also have come to Poland via Hungary, perhaps with a stay in the monastery in Somogyvár, and perhaps expressly to write about the Polish lands. The Anonymous—a sojourner in Poland—was the first to write of “the deeds of the princes of the Poles.” This was the title of his work, in Latin, Gesta principum Polonorum. Indebted to his hosts, the Anonymous wrote so as “not to eat Poland’s bread in vain.” He began, as did so many authors of his time, by praising the land to which he had come:

In a way, it seems to reflect the legend of Lech, who saw similar goodness in the land, while amplifying something that doubtless would cheer every Polish heart: that the land had never been subjugated by foreigners, despite their many attempts. To be sure, pri...