CHAPTER 1

AN ORDINARY NEIGHBORHOOD IN AN EXTRAORDINARY CITY

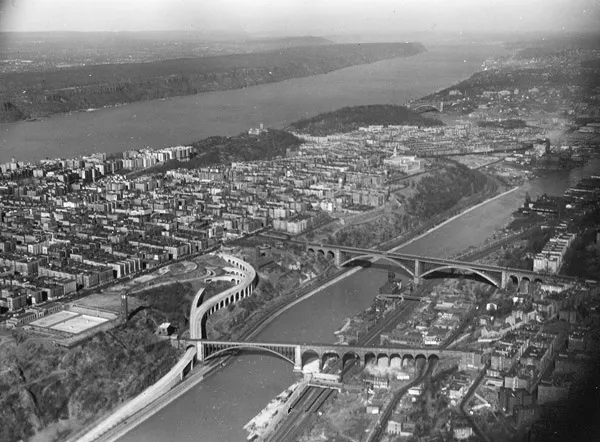

AT THE NORTHERN END OF MANHATTAN ISLAND, the landscape has always been more than a physical setting. For centuries, it has been something that people worked with and against to define their identities, their possibilities, and their ways of life in changing times.

Upper Manhattan is long and narrow. Two great ridges run south to north, leaving a valley between them. The western ridge overlooks the Hudson River; the eastern ridge looks down on the Harlem River. Both ridges end at Dyckman Street. The land north of Dyckman remains relatively flat on the east side of the island. On the west side, however, it rises to form Inwood Hill.

Long before Europeans arrived, native peoples lived around the eastern edge of Inwood Hill in a settlement widely referred to as Shorokapok. Archaeological investigations show that they hunted, farmed, fished, and gathered shellfish. As the archaeologists Anne-Marie Cantwell and Diana diZerega Wall note, it was not a wilderness when Europeans arrived—the indigenous people had already lived in the region for millennia—but an area dotted with small communities connected by paths. The inhabitants, the Munsee (sometimes called the Lenape), were a coastal people, skillfully taking advantage of the opportunities offered by a meeting of land and water in a fertile estuary. When Henry Hudson sailed into their domain in 1609, their territory was known as Lenapehoking, the Land of the People. The incoming Europeans, as the historian Gregory Dowd puts it, were “new people in an old world.”1

Figure 2: Washington Heights, framed by parks and rivers. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archives.

The earliest visitors to Lenapehoking were a mixed cast of explorers, adventurers, and traders drawn from an ocean world that washed against Europe, Africa, the Caribbean islands, and North America. Henry Hudson, an Englishman working under a contract with the Dutch East India Company, sailed past upper Manhattan in 1609, seeking a passage to China. He was soon followed by mariners with trade on their minds, but most of them were sojourners who did not linger long. The first of the newcomers to winter over was Juan Rodriguez, a man of African or mixed-race ancestry from the island of Hispaniola, which would one day harbor the Dominican Republic. Rodriguez sailed in on a ship captained by a Dutchman and set himself up as a trader in 1613. The European presence expanded, and by 1625 the Dutch West India Company had established the settlement of New Amsterdam, at the southern tip of Manhattan Island.2

Encounters between natives and strangers were shadowed by fatal incomprehensions and inescapable inequalities. Europeans and Munsee bargained and fought over the land under their feet. Although a folk tale suggests that Peter Minuit purchased Manhattan Island from the natives at a meeting place by Inwood Hill, no single deal sealed the fate of the Munsee. Instead, in negotiations framed by Dutch and English desires for acquisition and Munsee efforts to maintain a presence in the face of increasing numbers of Europeans, the natives tried “to buy time and protection.” In the end they failed. By the eighteenth century, the lands that make up modern New York had all been sold to settlers. The Munsee, as Cantwell and Wall put it, became “strangers in their own land.” It would not be the last time that comfortable residents of northern Manhattan found their world turned upside down by the arrival of new people.3

In 1776, when General George Washington and his officers drew up plans to defend Manhattan from British forces, a hill on the northwest end of the island was an obvious site for a fort. It was the highest point in Manhattan, with steep sides on all but its southern slope, and some 230 feet above a narrow spot in the Hudson River. The Americans built there a five-sided earthwork, Fort Washington, along with a riverside battery and outer works to the north, south, and east. Paired with another American fortification on the Jersey side of the river—Fort Lee—they could put British ships in the Hudson in a crossfire. Yet for all its geographic strengths, Fort Washington had a sad destiny.4

In August, British troops routed American forces from Brooklyn. In September, they landed on Manhattan Island and drove the Americans northward. Washington set up his headquarters in Mount Morris, the country mansion of a British colonel and departed Loyalist, near what is today the eastern end of West 161st Street. In October, however, Washington left Manhattan under the press of British forces. Troops at Fort Washington stayed behind. The garrison grew to 2,800: too many for the fort and too few to hold upper Manhattan.5

On November 15, 1776, British and Hessian forces attacked and captured Fort Washington. As the defeated American troops marched out of the fort, the victors laughed at them; some of the Americans were beaten and robbed. The captured fortress was renamed Fort Knyphausen, after a Hessian officer. An American outpost, where Margaret Corbin stepped in to replace her slain husband at his artillery piece during the fighting, was renamed Fort Tryon after the royal governor, Sir William Tryon. The Americans learned a lesson that would be repeated in northern Manhattan, especially in the section that came to be known as Washington Heights: geography is important, but it is not destiny.6

The area was largely rural into the middle of the nineteenth century, when wealthy New Yorkers bought the old farms and built suburban estates that looked and felt far from the crowded streets of downtown Manhattan. By the 1870s, the name Washington Heights was widely in use. The names of the landowners linger on the landscape. Audubon Avenue is named for John James Audubon, the artist, naturalist, and ornithologist whose wooded estate stood above the Hudson near what is now West 155th Street. Bennett Park in the Heights, on the site of Fort Washington, recalls James Gordon Bennett, publisher and editor of the New York Herald and a landowner in northern Manhattan.7 In rare locations, elements of the old patrician landscape remain—like the soaring entrance to the old Billings estate, Tryon Hall, which winds up toward Fort Tryon Park from the Henry Hudson Parkway.8

The Washington Heights of estates with river views began to change dramatically in the early twentieth century, when subways reached the neighborhood. In hilly northern Manhattan, contractors kept the subway on an even grade by laying tracks in deep underground tunnels. And that meant digging a tunnel more than two miles long northward from 158th Street beneath the ridge that defines the eastern Heights. On the night of October 24, 1903, when workmen tunneled through difficult rock north of St. Nicholas Avenue and 193rd Street, a three-hundred-ton boulder fell on a crew. Ten workers died; it was the worst disaster in the construction of the subway system.9

Still, in 1904, the Broadway line opened service to 157th Street; in 1906, it pushed on north to serve Inwood and Kingsbridge in the Bronx. The stage was set for massive real estate development in northern Manhattan. In the Heights, neighborhood boosters and real estate developers had hoped to create neighborhoods of “high-class residence property.” An article in the New York Times in 1908 noted the quickening pace of real estate development along Broadway between 133rd and 163rd streets. The next stretch of Broadway to see “high-class” growth would be between Broadway and the Hudson from 155th to 165th streets.10

Figure 3: The country in the city: the Billings estate atop Washington Heights. Collection of the New-York Historical Society.

Some of these predictions came true. In the early twentieth century, particularly in the southern end of the Heights, churches, cultural centers, and residential buildings suggested genteel aspirations for the neighborhood. The gothic revival Church of the Intercession at 155th and Broadway, consecrated in 1915 and set on a bluff amid the gently rolling lawns of Trinity Church Cemetery, seemed more like an Anglican country cathedral than an Episcopal church in Manhattan. Diagonally across from it on Broadway, at Audubon Terrace, there emerged a complex of educational and cultural institutions in ornate Italianate style. Advertisements for nearby apartment buildings touted their amenities, their views, their reasonable rents, and their proximity to the subway. The thirteen-story Riviera advertised suites of five to ten rooms; the nine-story Grinnell offered nine-room apartments and three duplexes.11

Both Washington Heights and Inwood had enclaves of affluence. But, overall, housing in the neighborhood was best suited to people of moderate income looking for an escape from crowded downtown neighborhoods like the Lower East Side, where densities topped 700 people per acre in 1910, compared to 161 people over the rest of the borough. Indeed, in 1910, one-sixth of all New Yorkers lived in Manhattan south of 14th Street.12

Figure 4: The city arrives: Broadway at 156th Street, 1920. Photograph by Arthur Hosking. Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

On the eve of the subway’s arrival, as the historian Clifton Hood points out, there was more available land in northern Manhattan and the Bronx than there was farther downtown. Developers had every incentive to build housing that could be put up fast at a low cost to provide rental income for landlords. In Washington Heights and Inwood, as in the Bronx, many developers built new-law tenements—exactly the kind of housing that would appeal to people jammed into older tenements further downtown.13

New-law tenements in northern Manhattan were particularly common east of Broadway. Erected under the Tenement House Act of 1901, these were an improvement over the old dumbbell tenement, with its awkward railroad-flat layout, limited airshaft ventilation, and shared toilets in the hallway. Each new apartment had to have running water, a water closet, and an exterior window. The narrow airshaft of the old dumbbell tenements was expanded to become more of a courtyard. Buildings aimed at more middle-class tenants boasted six stories and elevators.

The apartments east of Broadway often had ornate decorations on their facades but more modest interiors. They were a significant improvement for tenants over the congested streets downtown. The new apartments to be found in the Heights, as one resident, Leo Shanley, put it, were “grim, but comfortable.”14

A state law that granted tax breaks for residential housing construction fueled another housing boom in the 1920s. As vacancy rates climbed, tenants gained bargaining power against landlords: some bargained for a paint job, a new appliance, or a break on rent in exchange for signing a lease.15

With the completion of the IND subway line to the west of Broadway in 1932, the Heights and Inwood became even more accessible. By the end of the 1930s, the Heights had much of the face it would wear into the twenty-first century: simpler housing to the east of Broadway and more elaborate housing (like the art deco apartment buildings of upper Fort Washington Avenue) to the west. The George Washington Bridge opened in 1931, spanning the Hudson River between 179th Street and Fort Lee, New Jersey. Heading across the bridge toward New York in the late 1930s, you would have seen northern Manhattan’s defining landmarks: the Henry Hudson Parkway coursing along the river (albeit at the cost of ramming a highway through the hillside forests of Inwood Hill Park); the Cloisters, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s museum of medieval art, tall above the river on the ground that once held the Billings estate; and the ramparts of the Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center.16

Figure 5: Fort Tryon Park on the site of the old Billings estate. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archives.

The Jewish, Irish, and Greek New Yorkers who moved into Washington Heights were immigrants and the children of immigrants, drawn to the neighborhood by its affordable housing, good transit connections, and parks. New York is often described as a city of ambition, a place where big dreams propel ordinary people to the summits of riches and fame. The truth is both more complicated and more prosaic. While some New Yorkers harbor visions of wealth and power, far more define their hopes for a better life in more modest ways: a better job, a comfortable apartment, good schools for the children, and the prospect that life in New York City would be better than it might have been in a place left behind.

Consider Maria Anna Sofia Cecilia Kalogeropalos, who was born in New York in 1923 to recently arrived Greek immigrants. She grew up on 192nd Street in Washington Heights, where her father ran a drugstore. Until the Depression, her family enjoyed a modest prosperity. Despite some unhappiness in her family life, Maria went to neighborhood public schools, performed in school productions, and took trips downtown with her mother to Central Park and the New York Public Library. She sang in contests and on the radio. The highlights of her week, however, were entirely in Washington Heights: a regular Tuesday night dinner at a local Chinese restaurant and Sunday mornings singing in Saint Spyridon, the Greek Orthodox church that anchored northern Manhattan’s Hellenic community. Her eventual fame as the opera singer Maria Callas, won after her family left the Heights, was unusual. The pleasures she derived from everyday life in Washington Heights were typical.17

Despite its immigrant character, the neighborhood’s early history was not a story of easy racial or ethnic integration. In many ways, Washington Heights was born with a nasty tendency to keep others out. As early as the 1920s, when the modern neighborhood began to take visible form, there were tensions over inclusion. Blacks were the clear-cut victims of exclusionary practices, while Jews could be found among both victims and perpetrators.

In the 1920s Dr. Charles Paterno, a physician and real estate developer, noticed the quickening pace of real estate opportunities in the Heights. At 182nd Street and what is today Cabrini Boulevard, Paterno owned a mansion, built in 1907 and designed to look like a castle, with white marble interiors and an indoor swimming pool. Paterno wanted to preserve the value of his estate while developing his holdings in the Heights. His ultimate goal was to attract middle-class people who were already leaving the city for suburbs, where mock-Tudor homes were highly fashionable. Paterno’s solution was Hudson View Gardens, an elegant, carefully landscaped cooperative apartment complex designed in a Tudor style that offered suburban amenities in Manhattan.18

Dr. Paterno touted Hudson View Gardens with lavish advertisements, some of which were designed to be virtually indistinguishable from news stories. In his vision, Hudson View Gardens’ financin...