![]()

Sustainable Governance in the OECD- An Overview of Findings

Leonard Novy, Martin Brusis, Andrea Kuhn, Daniel Schraad-Tischler

A look at what’s behind the figures

The Sustainable Governance Indicators (SGI) project, which is available online at www.sgi-network.org, is much more than a substantial set of figures and calculations. Its products encompass more than three and a half thousand pages of assessment reports, along with the collective expertise of an international team of nearly 100 scholars. In this chapter, we will provide an overview of the wealth of data gathered as a part of the SGI, present the central findings and turn an analytical eye on some surprising correlations.

The SGI project as a whole is driven by the premise that the 30 developed industrial nations of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) face major challenges not only because the nature of individual problems has changed, but also because the national and international frameworks within which governments operate have undergone fundamental transformation in recent years. Clearly, problems associated with climate change, international terrorism and the growing wealth gap between industrial and developing nations all constitute a serious threat to the international order, and any attempts at their resolution will necessarily come within the framework of international cooperation.

Yet despite the pressures of internationalization and economic or political integration, industrial nations also face social and economic problems that are to some extent “homemade” and, therefore, a matter of national policy. These include structural and financial problems associated with states’ social security systems, issues of distributive or social justice (see Wolfgang Merkel and Heiko Giebler, in this publication), shortcomings in education systems, integration problems and problems associated with environmental protection. These are closely accompanied by grave secondary problems, such as a growing dissatisfaction with democracy among electorates or a loss of faith in the performance of democratic institutions and the structures of (social) market economies.

The financial market crisis underfolding as we write has dramatically demonstrated the extent to which global financial relations and open markets have altered the steering capacity of government policy. In a globalizing world, OECD nations find themselves exposed to rapidly intensifying competition on the basis of institutional efficiency and effectiveness, with their activities subjected to a rigorous test that rewards the most effective solutions and highlights specific weaknesses. This does not mean that globalization has succeeded in shaping all fields of politics and regions in a quasi-deterministic, universally valid manner or that globalization deprives national governments of the freedom to choose solutions in accordance with their own political and social welfare traditions. It does mean, however, that providing for public services as well as maintaining constitutional democracy and a market economy ruddered by sociopolitical concerns will, all in all, require continual adjustments. Reforms are therefore indispensable-but which ones?

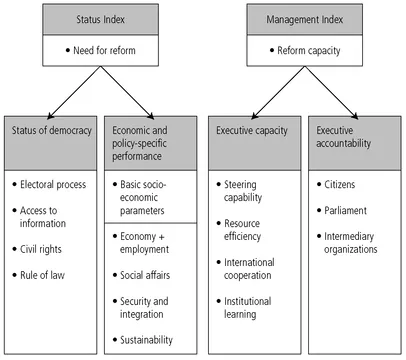

The need for reform and governments’ capacities for reform are thus the conceptual cornerstones of the SGI framework, which thereby aims to address the complexity of political reform processes in OECD states. Equally important-but qualitatively different in terms of how each can be assessed-, need and capacity are not combined into a single index but, rather, are addressed in two separate indices: the Status Index, which measures a country’s extant need for reform, and the Management Index, which assesses a government’s capacity to formulate and implement reforms as well as citizens’ capacity to hold their government accountable for its policies. Each of these indices is composed of two dimensions, which are further divided into categories and criteria.1

In designing the SGI, we adopted the well-tested method used by the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI), which has been evaluating 125 countries transitioning to democracy and a market economy since 2003 (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2007). Given that both features of state order-democracy and a market economy-can be assumed to be present in the case of OECD member states, the SGI’s examination of the need for reform focuses on the quality of a state’s democracy or of its economic and policy performance rather than on gaps or absent features.

Figure 1: Dimensions and categories of the Status and Management Indices

In calculating the overall results for the Status Index, the two dimensions “status of democracy” and “economic and policy-specific performance” are weighted equally. Whereas the first dimension measures the quality of a given state’s democratic order in terms of the categories “electoral process,” “access to information,” “civil rights” and “rule of law,” the second dimension outlines the contours of a state’s economic and political performance. This latter dimension draws upon basic socioeconomic data and examines in detail how past policies have performed in four areas: “economy and employment,” “social affairs,” “security and integration” and “sustainability.”

dp n="19" folio="22" ?The two dimensions of the Status Index are informed by the normative premise that the quality of a state’s democracy is critical to sustaining a high level of political, economic and social performance over the long term. Yet this quality can vary even within established democracies. In their study on policy and executive performance, which is based on SGI findings, Werner Jann and Markus Seyfried confirm this interlinkage, although clear causal relations are likely to be identified only over the course of time (see Jann and Seyfried, in this publication).

The Management Index is also composed of two dimensions: “executive capacity” and “executive accountability.” The first dimension, executive capacity, measures the extent to which the core executive is able to formulate, adopt and implement reform initiatives by means of the categories of “steering capability,” “resource efficiency,” “international cooperation” and “institutional learning.” Executive accountability, on the other hand, examines the participatory capacity of actors beyond the actual executive. The aim is to evaluate the extent to which parliament, political parties, associations and other civil society actors-by informing, communicating with and monitoring the core executive-contribute to improving the executive’s knowledge base as well as the level of its normative reflection.

The conditions of modern governance are thus factored into the SGI’s architecture. The project takes into account the fact that growing international economic and political interdependence impacts not only a government’s capacity to act (e.g., in the areas of economic and social policy), but also the manner in which it acts. Modern governance is exercised within the context of an increasingly dense network of state and non-state actors. This by no means renders irrelevant the activities of governments in facilitating their nation’s development. Indeed, the character or type of leadership pursued by a government is important, as are the structures and practices of its political-administrative system.

Thus, the manner in which governments deal with the challenges associated with increasingly urgent problems and changing frameworks is decisive. Just as it is misleading to speak of the deterministic effects of globalization or governance-induced problems spanning geographical borders and policy sectors, by the same measure, it would also be unrealistic to expect a uniform response to these challenges that befits all contexts (Scharpf 1997 and 1999).

dp n="20" folio="23" ?

The need for reform and reform capacity

In the following pages, we start with a discussion of the fundamental relationship between policy outcomes (i.e., the subject of the Status Index) and government performance (i.e., the subject of the Management Index) as established during the survey period between January 2005 and March 2007.2 This will be followed by a more detailed look at the particular strengths and weaknesses of selected states.

The wealth of data generated by the SGI necessitates a certain degree of distillation. The following classification of the 30 OECD countries into four groups is not based on any strict mathematical logic but, rather, on an initial appraisal of the comparative results. In this respect, the country groups serve as a structural support and reading aid, facilitating an improved visualization of the overall result.

At the top of both indices are the Nordic countries along with New Zealand, which has an Anglo-Saxon-influenced system. The middle cluster is divided into two groups, though there is a relative homogeneity among them. The group at the bottom is more diffuse, as there is an increasing distance between the values.

The distribution of the countries is surprising insofar as the standard typologies of democracy and governance used in comparative systems analysis do not sufficiently explain a given country’s performance in the two indices. A close analysis of these correlations shows, for example, that neither the traditional distinction between majoritarian democratic models and consensus democracies (Lijphart 1999) nor the distinction between federalist and unitary models adequately accounts for the differences in governance performance between the OECD states. Although different performance levels are commonly associated with these types of systems, SGI findings point instead to the art of governance as a more decisive factor.

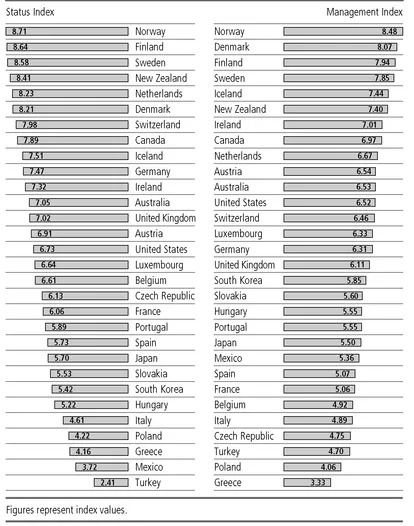

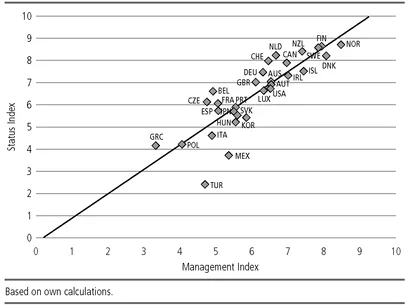

A look at the correlation between management performance and policy outcomes suggests that good management yields good perfor-mance. Few OECD countries display radically different rankings across the two indices. Those with comparatively high reform-capacity scores can be expected to see their need for reform decrease in the medium term and their status improve accordingly.

Figure 2: Status Index and Management Index results

dp n="22" folio="25" ?Figure 3: Status and Management Indices: scatter diagram for OECD countries

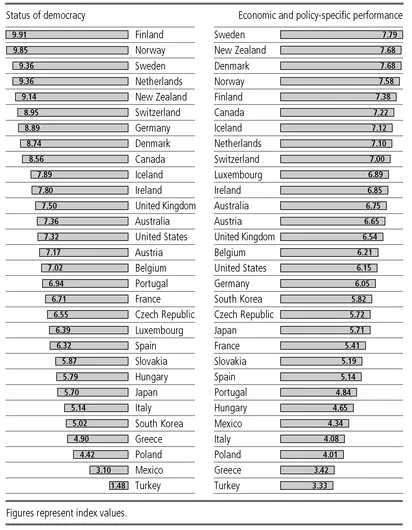

Status Index: The need for reform in 30 OECD countries

As outlined above-and due to individual problems as well as the changing national and international frameworks within which their governments operate-, the 30 OECD member states are under constant pressure to ensure the future viability of their societies. In order to develop a clear understanding of the different kinds of reform needed in OECD states, we present in the following pages the findings for the Status Index and explore issues of specific interest.

Strong performance paired with a high quality of democracy

Recording values of 8.2 and greater on the Status Index, Norway, Finland, Sweden, New Zealand, the Netherlands and Denmark are respectively ranked first to sixth. These countries, which have less need for reform than their peers, do not share common features in terms of geography or system typology. Whereas the Nordic countries dominate this group, high marks are also achieved by New Zealand, which reflects a classical Westminster model of government, and the Netherlands, which is shaped in every respect by the continental European tradition. However, all these countries do have small populations, and only the Netherlands has a population of more than 10 million. It has been shown that (at least economically) small countries perform better when they have a liberal trade regime (Alesina 2002). Although this type of liberal regime is a relatively marked feature of those countries at the top of the ranking, this thesis has yet to be analyzed in detail.3

Figure 4: Status Index results

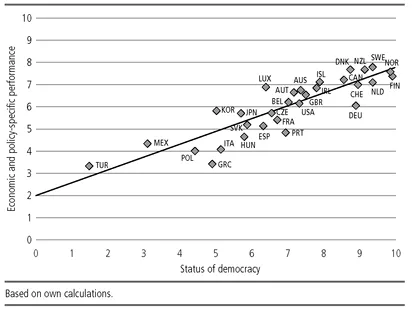

dp n="24" folio="27" ? Figure 5: Status Index: scatter diagram for OECD countries

The architecture of the SGI reflects an implicit relationship between the dimensions of status of democracy and political and socioeconomic performance, which appears to hold true and is depicted in Figure 5.4 Despite this correlation, countries with a low-level need for reform (i.e., highly ranked in the Status Index) receive a considerably higher rating for quality of democracy than they do for economic and policy-specific performance. The data presented in Table 1 show that there is an almost two-point difference in rankings across the two dimensions for any given country.

dp n="25" folio="28" ?Table 1: Status Index: countries ranked first to sixth

| Status Index: rank (score) | Status of democracy: rank (score) | Economic and policy-specific performance: rank (score) |

|---|

| 1 Norway (8.71) | 2 (9.85) | 4 (7.58) |

| 2 Finland (8.64) | 1 (9.91) | 5 (7.38) |

| 3 Sweden (8.58) | 3 (9.36) | 1 (7.79) |

| 4 New Zealand (8.41) | 5 (9.14) | 2 (7.68) |

| 5 Netherlands (8.23) | 3 (9.36) | 8 (7.10) |

| 6 Denmark (8.21) | 8 (8.74) | 2 (7.68) |

Status spotlight on Norway: A success story

Norway ranks at the top of both indices and, in the case of the Management Index (see below), by a considerable margin. As a dynamic and modern state capable of adapting to change, Norway stands out among the OECD countries in reform capacity. In the Status Index, Norway’s lead is tempered only by minimal shortcomings in the status of democracy dimension. Indeed, its otherwise flawless democratic record shows that Norway has problems controlling corruption. A cross-national comparison of data on corruption control affords Norway a rank of seventh among the 30 OECD states assessed.

What about Norway’s economic and policy-sector specific performance? During the period under review, Norway continued with sound economic and labor market policies. However, Norway’s enterprise policy earned lower marks for a lack of coherence, landing at the rank of 23rd. Nevertheless, Norway’s strong performance should not obscure the fact that its economic growth and sustainability remain closely linked to its natural resources. The Norwegian government has established an oil fund designed to secure the economic wealth generated by the country’s oil reserves. The income from oil sales should enable Norway to pursue a sustainable budget policy. The economic boom of recent years, which is itself partly oil-driven, to some extent accounts for the positive developments witnessed in the labor market. Surely, however, Norway’s model of flexicurity is also a key factor in this respect.

Norwegian family policy places substantial emphasis on the “social democratic” features of the Scandinavian model and successfully facilitates the participation of women in the labor market by means of an extensive system of day care. Measures such as child benefit payments as well as a uniform tax rate for married and unmarried couples further highlight the principle of social justice that lies at the heart of Norway’s family policy. It should come as no surprise, then, that Norway achieves a highly respectable fourth place on Merkel and Giebler’s Index of Social Justice, w...