- 98 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

How important is it to actually live a company's values? Values provide internal and external orientation and legitimize decisions and actions. They also send a signal that the company is a reliable cooperation partner. They can, therefore, help businesses lower their costs and improve their economic value creation. If lived values have such advantages, why is explicit-and effective-values management not as widespread as one might think? How do inconsistencies between propagated values and actual behavior arise, and what is the role that misled expectations among different stakeholders may play? Two case studies of internationally successful corporations illustrate the context and show how to leverage explicit values management.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Values Management and Value Creation in Business by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Values management and consistency

Andreas Suchanek, Martin von Broock

There is probably no company that openly describes itself as unreliable, irresponsible or untrustworthy. But, for a long time, it was also considered unnecessary to explicitly emphasize the opposite. This has changed. The issue of values management has rapidly gained importance in recent years. At least among major corporations, most if not all have probably addressed the topics of values, principles and mission statements.

And yet the issue is not necessarily new. It was in 1982 that Peters and Waterman published their bestseller In Search of Excellence and stressed, among other things, the importance of a system of values that is put into practice. Other publications, first and foremost those dealing with corporate culture, offer similar ideas. A prime example is the 1992 study by Kotter and Heskett, which found a significant positive correlation between an actively practiced values system and key financial indicators.

Supporting these observations about values1 are numerous statements by business executives. To cite but one example, in 2003, Booz Allen Hamilton interviewed managers from 150 leading companies in the German-speaking countries on the role of values. According to the study, 95 percent of those surveyed were convinced that values generate economic benefits (Booz Allen Hamilton 2003).

dp n="12" folio="16" ?We could cite other studies and statements by business leaders all over the world. A typical remark from a well-known CEO: “We have found that companies that have a written vision and values statement have a far greater return on investment than those that don’t.” But the source’s identity gives pause for thought: It was Jeff Skilling, foremost among those responsible for the Enron disaster, who made this comment at the 1998 general meeting of shareholders as he presented Enron’s new corporate values of respect, integrity, excellence and communication. As it soon turned out, Enron was more likely the typical example of not practicing these values in daily life.

This contrast between words and deeds points to a problem at the crux of values management: the twofold problem of the consistency of words and deeds. Inconsistency can arise when behavior does not correspond to communicated values. Inconsistency can also arise when communicated values create expectations that cannot be met, thereby generating perceived inconsistencies even though the company, for example, has done nothing worthy of reproach. We will explore both manifestations of the consistency problem in greater detail below.

In the first part of this book, we focus on the fundamental potentials of values management. In a certain sense, for example, the problem of consistency is central to a variety of arguments against the management of values. We explore some of these reasons and then present arguments for values management. This sets the stage for a systematic and comprehensive analysis of the key problem of consistency. After introductory considerations, we outline the central field of conflict between values and self-interest on the basis of ideas from game theory. Then, we elucidate the possibilities afforded by implicit values management, after which we discuss its limits.

The second part of this book takes up two case studies. The Hilti Group offers an example of how effective values management can contribute to change processes within a company. The BASF study investigates the extent to which values management can help or hinder innovation processes. In a final summary, we pull together the key conclusions from the first and second parts.

dp n="13" folio="17" ?Critical voices on values management

Officially, criticism of values is rarely heard.2 At most, statements might still be heard to the effect that there is no need to manage something as obvious as values-after all, they are the foundation of every reasonable business relationship. For example, here is Jack Welch in his book Winning almost poking fun at attempts to define and discuss values in a vacuum: “Who doesn’t know of a company that has spent countless hours in emotional debate only to come up with values that, despite the good intentions that went into them, sound as if they were plucked from an all-purpose list of virtues including ‘integrity, quality, excellence, service, and respect.’ Give me a break-every decent company espouses these things! And frankly, integrity is just a ticket to the game. If you don’t have it in your bones, you shouldn’t be allowed on the field” (Welch 2005: 14).

More than a few seasoned business leaders might share this view. Values, they would say, are quite natural-and also quite real. Thus, Welch continues: “By contrast, a good mission statement and a good set of values are so real they smack you in the face with their concreteness. The mission announces exactly where you are going, and the values describe the behaviors that will get you there. Speaking of that, I prefer abandoning the term values altogether in favor of just behaviors” (ibid.). One could well construe Welch’s statements as practically equating values management with leadership or good management. Values themselves don’t need special management, Welch seems to argue. Rather, it seems a waste of time, if not downright problematic, to talk about them at all.3

However, there are also skeptics who think that values-while useful for public-relations purposes-are irrelevant for the core business of business. Granted, this belief is hardly ever articulated in official statements or interviews. But one can assume that many a com-pany representative considers hard facts and figures much more important than concepts, such as respect, which are difficult to quantify. Fueling such skepticism is the fact that different companies usually have more or less the same values-respect, integrity, professionalism, partnership and so on-and, thus, there is little reason to think they could be turned into “unique selling points.” From this perspective, values are empty buzzwords with no economic importance.3

Interestingly, another argument occasionally raised takes quite a different tack. In this view, values are a luxury that companies in the competitive arena cannot afford. These critics evidently do not agree at all that values are just empty buzzwords. Rather, they see them as commitments, but commitments that-in the hard world of day-to-day business-necessarily entail costs and competitive disadvantages. Thus, no one can afford to meet them except in good times, if at all.

A final objection to be mentioned here is that explicit values management is too risky. In this view, values like these are unquantifiable, unmanageable and uncontrollable entities that, under certain circumstances, raise expectations that are impossible to fulfill.

We can summarize these four arguments as follows. Values are:

• fundamentally important for businesses but taken for granted and need no special managing.

• unimportant for businesses, because they are empty buzzwords.

• fundamentally important, but too expensive for businesses (i.e., a luxury).

• fundamentally important, but too difficult-and, hence, too risky- to manage.

These different criticisms and their contradictory nature indicate that values management is a complex issue and that managing values-to the extent that it turns out to be useful and possible-is an extremely demanding task.

To approach this task and its attendant opportunities and challenges, we will first take a closer look at what might be the advantages of actively practicing values in a company. Then, we will ask what obstacles to their implementation exist and how these can be dealt with.

The advantages of lived values

Like other comparable basic concepts (morality, trust, responsibility, etc.), the concept of “values” is so complex that it escapes precise definition. Therefore, we make no attempt to define it here. Instead, we describe its most important functions.

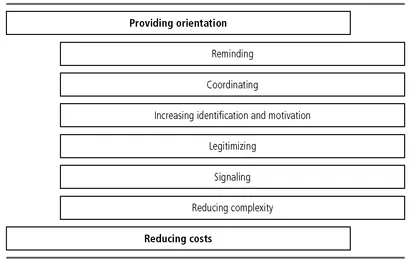

In principle, values always reflect an appraisal of a choice and, in doing so, also indicate that other options are worse. Thus, values- though only very generally-provide orientation for action. This is true initially for the one taking the action. To the extent that individuals have a sufficiently clear values system, they can align their decisions with it in the expectation of achieving what they find worthwhile.

Another function of values, and one that is often overlooked, could be called a reminder function. This has to do with the fact that values express something-and, hence, eventually remind people of something-that is literally considered valuable. Now, it is often the case that one’s attention is selective. Especially in the stress of daily life, people can lose sight of certain values, because they are preoccupied with the information, problem or issue immediately at hand. In such situations, the express reminder of certain values can have the effect of bringing them back to their attention.

As another fundamental function, values provide orientation for interactions. They can coordinate the decisions of several people. As long as those taking action share a common values system, are aware of this and trust each other, values can contribute to a considerable reduction in (transaction) costs. On the one hand, this applies to the costs of deciding which interests should be served, thereby narrowing the choices to their “valued” common interests. On the other hand, it also applies to the costs incurred when common goals and interests are not served or can be served only through elaborate controls and safeguards because of insufficient reliability or trust-that is, because a foundation of common values is missing.

These two orientation functions, the internal and the external, can also become relevant-and particularly for companies as corporate actors. 4 Internally, values can contribute significantly to identification and motivation. As would seem natural, employees who work in an atmosphere of mutual respect and transparent communication and who know they belong to a company that is seen as reliable and responsible are significantly more productive than unmotivated employees who simply work by the rules. Coupled with this is another function of values, that of legitimation, or endowing activity with meaning. This can prove particularly helpful when it comes to communicating difficult or painful decisions within the company in a way that conveys why they make sense. Thus, for example, references to safeguarding the company’s integrity can explain why a bank has declined to provide financing in a risky situation or why a company does not win a contract, because it would have required a kickback; either decision would have jeopardized the “asset” of integrity.

When practiced in everyday life, values can also have considerable importance externally. Here too, the function of legitimation can apply, when it comes to communicating the reasons for business decisions. A company can generally count on greater acceptance from external stakeholders if it gives reasons credibly backed up by values than if it only offers purely economic reasons.

Furthermore, values send a signal to potential partners, whether they are customers, investors, suppliers, government authorities or other entities, that contribute directly or indirectly to the creation of value. This signal says that the partner is dealing with a reliable and trustworthy company and need not fear being taken advantage of. It goes without saying that a customer or supplier is much more likely to be willing to work with that sort of company.

Another function is that of reducing complexity. This already plays a role in providing orientation, but it deserves separate mention, because, as we will later see, the increasing complexity of rules and standards increases the pressure to simplify. To the extent that cooperating partners can rely on each other’s integrity and responsibility, for example, they can dispense with complex rules and regulations-such as delivery contracts with quality assurance clauses and other agreements, employment contracts with numerous riders or other measures to secure each party’s interests-in favor of simpler, more general contracts and rules.

Figure 1: Functions of values management

To the extent that values are effectively signaled and actually accepted as the foundation of cooperation between partners who trust and rely on each other, they serve all of these functions, while also acting as an economic instrument for reducing costs. It is much more expensive-sometimes prohibitively so-to ensure mutual reliability through contracts, control mechanisms and sanctions alone. Another factor contributing to lower costs is improved risk management. This means avoiding the costs a company can incur as a result of violating statutory provisions and, in many cases, also the ethical convictions of the public or of certain stakeholders (particularly nongovernmental organizations)-costs that are often quite high.5 Some companies that come under the authority of the SEC are currently having exactly this experience: When the rules have been broken, proof of a functioning values management system can be grounds for lower penalties.

Two additional significant characteristics of values deserve mention here. For one, those who speak of values can ordinarily assume that their worth is generally acknowledged. We have already noted above that it is hardly ever possible to speak out seriously in public against values in the sense defined here. Therein lies an important reason why values can provide orientation, as well as one reason why more than a few people share Jack Welch’s view that they should be taken for granted.

The second noteworthy characteristic is the fact that values are fundamentally tied to subjects and their mental models.6 Even if there were such a thing as objective values, there would be no way to get around communicating them to people as individuals; subjectivity cannot be eliminated. This characteristic is important, because-particularly in a pluralistic society-it points to the problem of arriving at a common understanding (shared mental models) of values and their concrete implications in individual situations. We will explore this issue in greater detail at a later point.

In summary, it can be said that values can, in fact, make a considerable economic contribution to a company in that they can provide individual and corporate actors with internal and external orientation, improve the conditions for initiating cooperation by signaling reliability and trustworthiness, and reduce the costs of such cooperation.

Against this backdrop, the questions arise: If lived values have such advantages, what is the basis for criticizing them? Why is the implementation of a “good” values management system not more widespread?

The crucial problem: consistency

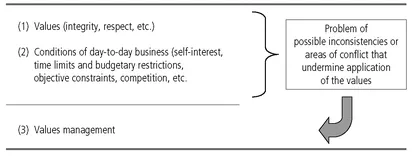

The best way to begin answering these questions is to understand that the purpose of values is to guide certain actions and rule out others. The central challenge clearly lies in establishing consistency-as coherence-between each communicated value and the expectations arising from it, on the one hand, and the actual behavior, on the other.

The two sides of the consistency problem and the implications of conditions for action

This relationship, which at first appears simple, soon proves challenging in light of the complex conditions under which decisions must be made and actions taken in businesses-conditions that not uncommonly necessitate compromise. Figure 2 lays this out:

dp n="20" folio="24" ?Figure 2: The consistency problem

The problem of consistency arises, first of all, because it is much simpler and less costly to say something-or decide to do something-than to actually follow through on it.7 This is explained by the fact that taking action and following through are always influenced by a wide variety of conditions: budgetary restrictions, market conditions, competitive pressure, institutional policies, time limits, unforeseen mechanical breakdowns ...

Table of contents

- Titel

- Impressum

- Preface

- Einleitung

- Values management and consistency

- The case studies: Introduction

- “Less is more”- Values management and the introduction of “Beyond Budgeting” at Hilti

- Values management and innovation at BASF

- Summary and conclusions

- Bibliography

- The authors