![]()

Chapter 1

Orchids in folklore and medicine

Orchids are the largest family of blooming flowers with over 25,000 species and approximately 900 genera, many of them cultivated as house plants. They are somewhat difficult to grow owing to their need for filtered light and high humidity, but wild orchids grow worldwide and can be found in every continent except Antarctica, thriving mainly in tropical and sub-tropical climates.

Orchid plants and flowers range in size and shape. Many grow in tropical forests, producing delicate blooms in a wide array of colours. They vary in size from a few inches to the towering vines of the Vanilla orchid.

These beautiful exotic plants have long been associated with romance, love and sex. In fact, the name Orchids (Orchidaceae family) derives from the Greek word orchis, meaning testicle, which their fleshy underground tubers were thought to resemble.

Various cultures around the world used orchids in sexual and fertility rituals. The Turks, for example, made ice cream from orchid tubers to enhance male performance and in Africa, men used Ansellia leaves on their wedding day to produce male children. In various rituals in Asia, women used Dendrobium to increase fertility.

In the Middle Ages, Europeans were recorded to have seen slipper orchids sprout from the ground where animals had mated. There is also the exotic story of the Filipino Queen who climbed a tree waiting for her husband to return from a battle. She transformed herself into Vanda coerulea, whose flower pattern matched her pale blue gown.1

In more delicate settings, orchids have been thought to symbolise desirable attributes. These include love, beauty, fertility, refinement, thoughtfulness and charm. They come in every colour except true blue (a tinted blue variety exists). Red orchids symbolise passion, white orchids purity, yellow orchids joy and green orchids good fortune.2

1.1Medicinal Orchids

With their ancient association with sex and fertility, it should not be surprising that orchids have found their way into traditional medicine pharmacopeia, where their therapeutic claims extend far beyond sex and fertility tonics to an enormous range of uses, including neurological conditions, skin diseases, bleeding, coughing, traumatic injuries and cardiovascular diseases.

Most of the medical claims of orchids have not been subjected to modern randomised clinical trials (RCTs), and the few that have rarely turn out positive, which would appear to be surprising considering the large number of alkaloids in orchid tissue.3 However, like most of traditional medicine, including Ayurvedic and Chinese medicine, there are extensive anecdotal records and case studies that suggest that some of the vaunted therapies may well have a basis in clinical experience, but have escaped validation owing to methodological limitations of RCTs and the lack of interest in conducting well-designed observational studies.

Some healing herbs may be found in National Orchid Garden, Singapore (Photo credit: Soh Shan Bin).

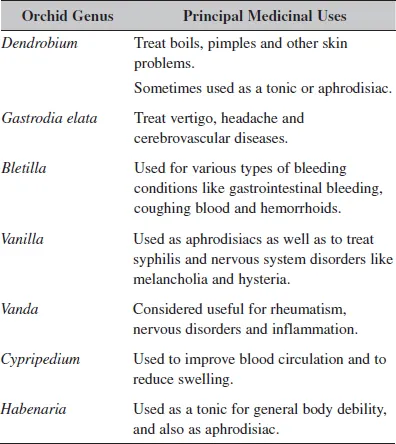

Seven genera of orchids have been selected to illustrate the rich diversity of medicinal applications of orchids.

One of them, Gastrodia elata, has been subjected to more rigorous study at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Some of the findings and analyses from a biomedical standpoint are presented here to give the reader a flavour of the kind of scientific studies that can and have been done on therapy with orchids. Unfortunately, not enough of such studies have been conducted. Traditional users of medicines derived from orchids have, for the time being, to be content with placing their faith in the experience of traditional physicians, past and present, as well as diverse anecdotal records of their healing properties.

The rest of this volume presents medicinal orchids for the general public and orchid enthusiast. The seven orchid genera covered, which include dozens of species within them, offer a good representation of the very diverse medicinal use of orchids. Among these genera, Dendrobium, Gastrodia and Bletilla striata (Baiji) have been used by Chinese herbalists for thousands of years. Others like Habenaria and Cypripedium enjoy enduring applications in Ayurvedic medicine.

Selection of Orchids and Their Principal Medicinal Uses

We hope that this little book will help stimulate public interest in orchids and their medicinal uses, and provide readers with a flavour of the potential wonders of healing that may be found in these remarkably colourful and exotic plants, and that more research work may be invested in unearthing the exciting medical potential in them.

![]()

Chapter 2

Phytochemical and pharmacological studies

To enable readers to better appreciate the biomedical properties of orchids, we would like to introduce a number of technical terms used in plant biochemistry. Traditional medical systems like Chinese medicine do not use these terms in explaining their medical uses, but instead describe their therapeutic effects using conceptual constructs like qi, jing, yin, yang, “dampness” and “wind”. It is comforting to know that it may be possible in some cases to explain these medicinal properties in biomedical terms.

Some common terms used in phytochemistry, the study of the many chemical compounds that are naturally derived from plants, are briefly explained below. Readers who are already familiar with these terms, or with less interest in biomedical explanations, may skip this chapter.

Metabolites are organic compounds that are starting materials in metabolism processes. They are simple small structures like vitamins and amino acids absorbed by living organisms and can be used to construct more complex molecules or broken down into simpler ones. Intermediary metabolites may be synthesised from other metabolites and often release chemical energy. For example, glucose can be synthesised to form starch or glycogen, and can be broken down during respiration to obtain chemical energy.4

In plants, secondary metabolites are produced by the plant itself, but they are not required for the survival of the plant. These substances may be involved in various processes such as inducing flowering, fruit set and abscission. In other words, these substances are required for the formation of flowers and fruits, as well as the detachment of the fruit from the plant. They also act as anti-microbials as well as attractants or repellents, and have various other effects on the plant itself and on other living organisms. Hence in the study of herbal medicine, these chemical compounds are researched as potential sources of new drugs for treatment of diseases.

With their long and rich tradition of use in healing, orchids are frequently researched for their secondary metabolites. Among these, flavones, anthocyanins, alkaloids, allergens and photoalexins are the most commonly studied.

Alkaloids act on the nervous system. Many alkaloid stimulants such as morphine, cocaine and nicotine are addictive. Alkaloids in orchids fall into two main classes: the pyrrolizidine- and dendrobine-type alkaloids. The genus Dendrobium is the richest in alkaloids. The first alkaloid isolated from the orchids was dendrobine. This alkaloid is known to relieve pain, lower blood pressure and augment salivary secretions.5 More than 14 other dendrobine-type alkaloids have been discovered from various Dendrobium species. These alkaloids are useful pharmacologically but must be used with caution, as in sufficient quantity they can be toxic to humans.

Phenanthrenes occur in higher plants, particularly in orchids, and have received much attention for their cytotoxic properties against specific human cancer cells. This anti-tumour effect is an important reason for much research being conducted on them.

Denbinobin, which is isolated from Dendrobium nobile, is one of the phenanthrenes known to have quite potent cytotoxic effects in vitro and in vivo. Phenanthrenes found in other orchid species are found to have anti-allergic, anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, anti-oxidant and anti-thrombotic properties. It has been reported that several chemical compounds with anti-microbial properties have been isolated from orchid species Bletilla striata.

Phytoalexins, which are bacteriostatic and fungistatic, inhibit the growth of bacteria and fungi. They are usually produced in small amounts in plants and do not cause problems when consumed by humans unless taken in excess. Good agricultural practice does help to reduce the amount of photoalexins found in cultivated orchids.

Stilbenoid, a plant-based chemical compound, has biological effects like anti-inflammation, cancer prevention and protection of heart muscles. Resveratrol, a well-known stillbenoid, is also a phytoalexin. It is present on the surface of grapes and is known to help ward off fungi and bacteria on fruits. Claims have been made that it has beneficial effects on plants and animals, such as promoting cell regeneration, but it is also thought to have cytotoxic effects.

Other chemical compounds such as gigantol and moscatilin have been isolated from Dendrobium nobile and found to have anti-mutagenic properties. The chemical compounds found in Gastrodia elata, mainly gastrodin and vanillin, possesses anti-inflammatory, anti-coagulation, anti-angiogenic and anti-convulsive properties. Gastrodin also has sedative actions on mice and humans, and might be effective medicine for conditions like anxiety, insomnia, neurasthenia and mental hyper-excitation. Research has shown that gastrodin and vanillin have similar pharmacological mechanisms to that of DOPA drugs used for Parkinson’s disease.

![]()

Chapter 3

Dendrobium

3.1I...