![]() III. Austrian Refugees/Migrants

III. Austrian Refugees/Migrants

in the World War II Era:

Staying or Returning?![]()

“You did not have to feed me, nor to clothe, nor to educate me; I came complete”: Dietrich W. Botstiber’s Escape from the City of Music

Robert Lackner

On October 8, 1938, a twenty-five-year-old engineer from Austria arrived at the port of New York. When he got off the French ocean liner “Île de France” and entered the United States for the first time in his life, he had nothing but a seal ring, a gold cigarette case, a small piece of gold and some change.1 Almost six decades later, he established a foundation which since then has spent millions of dollars on charity and philanthropic projects and has significantly fostered the transatlantic academic exchange. Until today, more than fourteen years after its founder passed away in 2002, its intention still is, among others2, “to promote an understanding of the historic relationship between the United States and Austria”3.

What happened during the years between 1938 and 1995 seems to have been the American dream. A more or less penniless refugee from a desperate country in Central Europe without any useful contacts and with few prospects had great professional success and became a millionaire, a true American, and, in E. Wilder Spaulding words4, a quiet invader who presumably assimilated into the society of his new home land very quickly.

So what were the reasons for this remarkable development? Before we can try to find an answer to that question, we need to figure out who this immigrant, who after his arrival quickly changed his name from Wolf-Dietrich to the more American-sounding Dietrich W. and also called himself Derrick afterwards actually was.

Dietrich W. Botstiber was born in Vienna on November 17, 1912. Both his parents were active in the music business. His mother Luisa was a professionally trained alto singer who came from a wealthy Roman-Catholic family originating from the capital of the Habsburg Empire. His father, on the other hand, was the son of Jewish immigrants from Hungary, who had been extraordinarily successful as a music manager. After Botstiber had studied law and musicology at the University of Vienna, he had held high administrative positions at key institutions of Vienna’s music scene such as the Wiener Konzertverein, the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, and the Academy of Music and Performing Art. A year after Dietrich’s birth, he took over the management of the newly-founded Wiener Konzerthaus, which was to emerge into one of the most important concert venues of the country and a stronghold of avant-garde music.5 For that reason, Dietrich grew up in an environment that was dominated by Viennese high culture and the fine arts. His family resided in the district of Grinzing and owned a villa at Kaasgrabengasse, next to well-known figures from cultural life such as the composers Alexander Zemlinsky and Egon Wellesz and the writer Elias Canetti. Among their neighbors, there were also Peter and Gerhart Drucker, who were Dietrich’s boyhood friends and who both immigrated to the United States during the 1930s and became very successful in medicine and the academic field.6

Portrait of Dietrich W. Botstiber

Source: The Dietrich W. Botstiber Foundation.

Dietrich attended elementary school in Vienna, where one of his teachers was Sigmund Freud’s daughter Anna, and then moved on to the Humanistisches Gymnasium, i.e. high school. After his graduation, he enrolled at the Technical University of Vienna and earned a degree in electrical and mechanical engineering in 1935. Due to the Anschluss in 1938, he was not able to finish his dissertation on semi-conductors, which he had started at the Institute of Experimental Physics of the University of Vienna. After months of fear and threats against his family, he finally managed to leave Austria in September 1938 and arrived in New York in October, while his parents and his sister Eva stayed in Vienna. He never was to see his father again, who went into exile in Great Britain in 1939 and died in the city of Shrewsbury close to the Welsh border in January 1941.

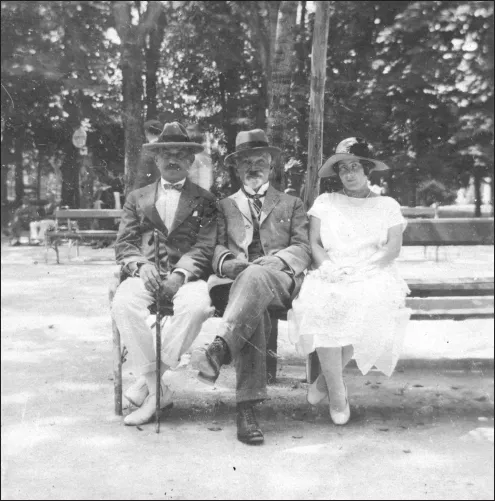

Dietrich Botstiber with his parents Luisa and Hugo and his sister Eva, Vienna 1919.

Source: Private Collection of Christina Stahl.

At that time, Dietrich had already established himself in the United States. He had moved to Philadelphia, where he had found a job as electrician and subsequently built up a career. After he had worked in a variety of jobs and had been naturalized in 1943, he started working for the Piasecki Helicopter Corporation in 1947 and became its chief mechanical engineer in 1951. Only a year later, he finally launched his own business named Technical Development Company (TEDECO), which designed and manufactured aircraft engine accessories. When Dietrich retired and sold the company in 1985, it had 235 employees and annual sales totaling 20 million dollars.7

In this respect, the impact his professional activities had on America was tremendous and probably much bigger than he had expected when he had left Austria in 1938. In his autobiography Not on the Mayflower, which was published posthumously and which is the most significant and almost only source about his life, he briefly describes what being an American meant to him and what he had achieved for the country that had given him shelter:

Dear Uncle Sam: It was a privilege to be with you for the past fifty-some years. I hope I have not been a burden to you. I tried not to. To my knowledge, I have not caused you any great expenses. You did not have to feed me, nor to clothe, nor to educate me; I came complete. I tried to be useful to you; I worked for everything I got and created jobs, new jobs that would not have existed without me, for about two hundred and fifty of your other nephews. I sold the results of our work to the world; I hope that did a bit for your trade balance. I know that all that is small in comparison to what you gave me; that one thing I had wished and longed for, and had waited for seven years to get: that rubber stamp in my passport, fifty-some years ago. And what it implies. Your grateful nephew...8

Dietrich Botstiber’s parents Hugo and Nina and his grandfather Ignaz (center), Vienna 1926.

Source: Private Collection of Christina Stahl

Interestingly enough, Dietrich was not the first one in his family to immigrate to the United States and to obtain U.S. citizenship, which shifts the focus to previous generations of Botstibers; migration was a recurring event in Dietrich’s family history.

As mentioned above, his father Hugo’s Jewish ancestors had come to Vienna only during the second half of the nineteenth century due to political and economic reasons. His grandfather Ignaz, who initially had been a Hausierer (a peddler) and a lumber merchant from a small town in Western Hungary, came to the capital of the Habsburg Empire during the 1870s9, where he embarked on several business projects managed to make some money. But after he had lost his newly-acquired wealth, he left Vienna together with his wife Nina and his children Ida and Hugo, after the latter had graduated from high school, and went to the United States in 1893.10 After their arrival in New York, they lived on Bedford Avenue in Brooklyn and later moved to 72nd Street in Manhattan. There, the family became acquainted with two sisters of Sigmund Freud, Paula and Anna, and Anna’s husband Ely Bernays.11 Bernays was actually an entrepreneur from Germany but had lived in Vienna for ten years before moving on to the United States, together with his wife and his son Edward, the future founder of modern public relations.

Like the Bernays, the Botstibers found economic success in America. At the turn of the century, Ignaz and Nina opened a ladies’ novelties shop at Lispenard Street close to Canal Street in Lower Manhattan, importing and manufacturing fancy goods, notions and small wares.12 As their business prospered, they moved their premises to a superior location on Broadway and were able to afford an appartement in a fancier area in Manhattan and hire a housemaid.13 When they were finally naturalized in July 190614, thirteen years after after their arrival, we can assume that they had fairly well assimilated into the American mainstream, in contrast to Dietrich’s father Hugo. At the age of eighteen, the latter had come with his parents to New York, where he gave piano lessons in order to contribute to the family’s income15, but had returned to Vienna already before mid-1894. Apparently, he did not appreciate life in the United States and especially not as an immigrant in New York, although he returned twice during the subsequent years, probably in order to visit his parents.

Hugo rejected America because of his adoration for music and the fine arts which made Vienna the place for him to be. As Dietrich recalls, his father never talked about the time he had spent overseas as a young man. But Dietrich, who as a six-year-old experienced the hardship in the aftermath of the First World War and who probably did not understand what happened to his country, soon started to consider the United States a remote paradise:

But far away, there was America. People there had money. […] America was big. America was rich. America was strong. In America, everybody had an automobile. In America, the locomotives were big and fast. Buildings were high. But America had no culture, my father had said to me. He had been there, I learnt to my surprise. I asked him about it, but he did not tell much.16

Dietrich thus realized how different they were. His father “was not impressed by large new buildings, factories, and great bridges; he looked for things of ancient beauty”17. As this contrast is very essential in order to understand Dietrich’s future development, we need to put particular emphasis on it. For he extensively comments in his memoirs on the difficult relationship to his father, which was marked by a severe feeling of inferiority, as the following paragraph shows:

But I had to realize that I was a problem to my father all along. As a child, I had been sickly, thin, small, nervous and undernourished. I had had every childhood disease I had ever heard of. I had no special talents; I could not draw or paint […], my violin playing was mediocre […], and I showed no ambition in this field. To my father, whose whole life centered around music, this must have been a great disappointment.18

In this respect, it is no wonder that he rejected his father’s Viennese universe of music and preferred to concentrate on a subject that was allegedly alien to him19, science and technology. Instead of the Latin and Greek classes at the Humanistisches Gymnasium, he longed for a more practical education:20

I wanted to go to a school that taught me about life as it was today, not in the past, a school that would open up the natural world for me, a place where science was rega...