CHAPTER I. INDUSTRY.

IT is melancholy to compare the present state of Egypt with its ancient prosperity, when the variety, elegance, and exquisite finish displayed in its manufactures attracted the admiration of surrounding nations, and its inhabitants were in no need of foreign commerce to increase their wealth, or to add to their comforts. Antiquarian researches show us that, not only the Pharaohs and the priests and military chiefs, but also, a great proportion of the agriculturists, and other private individuals, even in the age of Moses, and at a yet earlier period, passed a life of the most refined luxury, were clad in linen of the most delicate fabric, and reclined on couches and chairs which have served as models for the furniture of our modern saloons. Nature is as lavish of her favours as she was of old to the inhabitants of the valley of the Nile; but, for many centuries, they have ceased to enjoy the benefit of a steady government: each of their successive rulers, during this long lapse of time, considering the uncertain tenure of his power, has been almost wholly intent upon increasing his own wealth; and thus, a large portion of the nation has gradually perished, and the remnant, ill general, been reduced to a state of the most afflicting poverty.

The male portion of the population of Egypt being scarcely greater than is sufficient for the cultivation of as much of the soil as is subject to the natural inundation, or easily irrigated by artificial means, the number of persons who devote themselves to manufactures in this country is comparatively small; and as there are so few competitors, and, at present, few persons of wealth to encourage them, their works in general display but little skill.

Painting and sculpture, as applied to the representation of living objects, are, I have already stated, absolutely prohibited by the Mohhammadan religion: there are, however, some Moos'lims in Egypt who attempt the delineation of men, lions, camels, and other animals, flowers, boats, &c., particularly in (what they call) the decoration of a few shop-fronts, the doors of pilgrims' houses, &c.; though their performances would be surpassed by children of five or six years, of age in our own country. The art in which the Egyptians most excel is architecture. The finest specimens of Arabian architecture are found in the Egyptian metropolis and its environs; and not only the mosques and other public buildings are remarkable for their grandeur and beauty, but many of the private dwellings, also, attract our admiration, especially by their interior structure and decorations. Yet this art has, of late years, much declined, like most others in this country: a new style of architecture, partly Oriental and partly European, and of a very plain description, being generally preferred. The woodwork of the doors, ceilings, and windows of the buildings in the older style, which have already been described, display considerable taste, of a peculiar kind; and so, also, do most of the Egyptian manufactures; though many of them are rather clumsy, or ill finished. The turners of wood, whose chief occupation was that of making the lattice-work of windows, were very numerous, and their work was generally neater than it is at present: they have less employment now; as windows of modern houses are often made of glass The turner, like most other artisans in Egypt, sits to his work. In the art of glass-making, for which Egypt was so much celebrated in ancient times, the modern inhabitants of this country possess but little skill: they have lost the art of manufacturing coloured glass for windows; but, for the construction of windows of this material they are still admired, though not so much as they were a few years ago, before the adoption of a new style of architecture diminished the demand for their work. Their pottery is generally of a rude kind: it mostly consists of porous bottles and jars, for cooling, as keeping, water. For their skill in the preparation of morocco leather, they are justly celebrated The branches and leaves of the palm-tree they employ in a great variety of manufactures: of the former, they make seats, coops, chests, frames for beds, &c.: of the latter, baskets, panniers, mats, brooms, fly-whisks, and many other utensils. Of the fibres, also, that grow at the foot of the branches of the palm-tree are made most of the ropes used in Egypt. The best mats (which are much used instead of carpets, particularly in summer) are made of rushes. Egypt has lost the celebrity which it enjoyed in ancient times for its line linen: the linen, cotton, and woollen cloths, and the silks now woven in this country are generally of coarse or poor qualities.

The Egyptians have long been famous for the art of hatching fowls' eggs by artificial heat. This practice, though obscurely described by ancient authors, appears to have been common in Egypt in very remote times. The building in which the process is performed is called, in Lower Egypt, ma'amal el-fira'kh, and in Upper Egypt, ma'amal el-furroo'g: in the former division of the country, there are more than a hundred such establishments; and in the latter, more than half that number. The proprietors pay a tax to the government. The ma'amal is constructed of burnt or sundried bricks; and cousin of two parallel rows of small chambers and ovens, divided by a narrow, vaulted passage. Each chamber is about nine or ten feet long, eight feet wide, and five or six feet high; and has above it a vaulted oven, of the same size, or rather less in height. The former communicates with the passage by an aperture large enough for a man to enter; and with its oven, by a similar aperture: the ovens, also, of the same row, communicate with each other; and each has an aperture in its vault (for the escape of the smoke), which is opened only occasionally: the passage, too, has several such apertures in its vaulted roof. The eggs are placed upon mats or straw, and one tier above another, usually to the number of three tiers, in the small chambers; and burning gel'leh (a fuel before mentioned, composed of the clung of animals, mixed chopped straw, and made into the form of round, flat cakes) is placed upon the floor of the ovens above. The entrance of the ma'amal is well closed. Before it are two or three small chambers, for the attendant, and the fuel, and the chickens when newly hatched. The operation is performed only during two or three months in the year; in the spring; earliest in the most southern parts of the country. Each ma'amal in general contains from twelve to twenty-four chambers for eggs and receives about a hundred and fifty thousand eggs, during the annual period of its continuing open; one quarter or a third of which number generally fail. The peasants of the neighbourhood supply the eggs: the attendant of the ma'amal examines them; and afterwards usually gives one chicken for every two eggs that he has received. In general, only half the number of chambers are used for the first ten days; and fires are lighted only in the ovens above these. On the eleventh day, these fires are put out, and others are lighted in the other ovens, and fresh eggs placed in the chambers below these last. On the following day, some of the eggs in the former chambers are removed, and placed on the floor of the ovens above, where the fires have been extinguished. The general heat maintained during the process is from 100° to 103° of Fahrenheit's thermometer. The manager, having been accustomed to this art from his youth, knows, from his long experience, the exact temperature that is required for the success of the operation, without having any instrument, like our thermometer, to guide him. On the twentieth day, some of the eggs first put in are hatched; but most, on the twenty-first day; that is, after the same period as is required in the case of natural incubation. The weaker of the chickens are placed in the passage: the rest, in the innermost of the anterior apartments; where they remain a day or two before they are given to the persons to whom they are due. When the eggs first placed have been hatched, and the second supply half-hatched, the chambers in which the former were placed, and which are now vacant, receive the third supply; and, in like manner, when the second supply is hatched, a fourth is introduced in their place. I have not found that the fowls produced in this manner are inferior in point of flavour or in other respects to those produced from the egg by incubation. The fowls and their eggs in Egypt are, in both cases, and with respect to size and flavour, very inferior to those in our country.—In one of the Egyptian newspapers published by order of the government (No. 248, for the 18th of Rum'ada'n, 1246, or the 3d of March, 1831 of our era) I find the following statement.

| Lower Egypt. | Upper Egypt. |

| Number of establishments for the hatching of fowls' eggs in the present year | 105 | 59 |

| Number of eggs used | 19,325,600 | 6,878,900 |

| Number spoiled | 6,255,867 | 2,529,660 |

| Number hatched | 13,069,733 | 4,349,240 |

Though the commerce of Egypt has much declined since the discovery of the passage from Europe to India by the Cape of Good Hope, and in consequence of the monopolies and exactions of its present ruler, it is still considerable.

The principal imports from Europe are woollen cloths (chiefly from France), calico, plain muslin, figured muslin (of Scotch manufacture, for turbans), silks, velvet, crape, shawls (Scotch, English, and French) in imitation of those of Kashmee'r, writing-paper (chiefly from Venice), fire-arms, straight sword-blades (from Germany) for the Nubians, &c., watches and clocks, coffee-cups and various articles of earthenware and glass (mostly from Germany), many kinds of hard-wares, planks, metal, beads, wine and liqueurs; and white slaves, silks, embroidered handkerchiefs and napkins, mouthpieces of pipes, slippers, and a variety of made goods, copper and brass wares, &c., from Constantinople:— from Asia Minor, carpets (among which, the segga'dehs, or small prayer-carpets), figs, &c.:—from Syria, tobacco, striped silks, 'abba'yehs (or woollen cloaks), soap:— from Arabia, coffee, spices, several drugs, Indian goods (as shawls, silks, muslin, &c.):—from Abyssinia and Senna'r and the neighbouring countries, slaves, gold, ivory, ostrich-feathers, koorba'gs (or whips of hippopotamus' hide) tamarind in cakes, gums, senna:—from El-Ghurb, or the West (that is, northern Africa, from Egypt westwards), turboo'shes (or red cloth scull-caps), boornoo'ses (or white woollen hooded cloaks), hhera'ms (or white woollen sheets, used for night-coverings and for dress), yellow morocco shoes.

The principal exports to Europe are wheat, maize, rice, beans, cotton, flax, indigo, coffee, various spices, gums, senna, ivory, ostrich-feathers:—to Turkey, male and female Abyssinian and black slaves (including a few eunuchs), rice, coffee, spices, hhen'na, &c.:—to Syria, slaves, rice, &c.:—to Arabia, chiefly corn:—to Senna'r and the neighbouring countries, cotton and linen and woollen goods, a few Syrian and Egyptian striped silks, small carpets, beads and other ornaments, soap, the straight sword-blades mentioned before, fire-arms, copper wares, writing-paper.

There are in Cairo numerous buildings called Weka'lehs, chiefly designed for the accommodation of merchants, and for the reception of their goods. The Weka'leh is a building surrounding a square or oblong court. Its ground-floor consists of vaulted magazines, for merchandize, which face the court; and these magazines are sometimes used as shops. Above them are generally lodgings, which are entered from a gallery extending along each of the four sides of the court; or, in the place of these lodgings, there are other magazines; and in many weka'lehs which have, apartments intended as lodgings, these apartments are used as magazines. In general, a weka'leh has only one common entrance; the door of which is closed at night, and kept by a porter. There are about two hundred of these buildings in Cairo; and three-fourths of that number are within that part which constituted the original city.

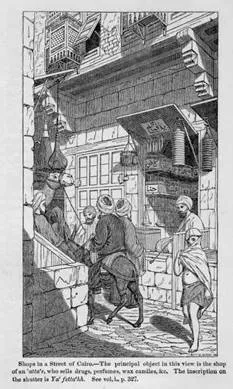

It has already been mentioned, in the introduction to this work, that the great thoroughfare streets of Cairo generally have a row of shops along each side, not communicating with the superstructures. So, also, have many of the by-streets. Commonly, a portion of a street, or a whole street, contains chiefly, or solely, shops appropriated to one particular trade; and is called the Soo'ck (or Market) of that trade; or is named after a mosque there situated. Thus, a part of the principal street of the city is called “Soo'ck en-Nahh'hha'see'n”, or the market of the sellers of copper wares (or simply “the Nahh'hha'see'n”—the word “Soo'ck” being usually dropped); another part is called “the Go'hargee'yeh,” or [market of] the jewellers: another, “the Khoordagee'yeh,” or [market of] the sellers of hardwares; another, “the Ghoo'ree'yeh,” or [market of] the Ghoo'ree'yeh, which is the name of a mosque situated there. These are some of the chief soo'cks of the city. The principal Turkish soo'ck is called “Kha'n El-Khalee'lee.”

Some of the soo'cks are covered over with matting, or with planks, supported by beams extending across the street, a little above the shops, or above the houses.

The shop (dookka'n) is a square recess, or cell, generally about six or seven feet high; and between three and four feet in width. Its floor is even with the top of a mus'tub'ah, or raised seat of stone or brick, built against the front. This is usually about two feet and a half, or three feet, in height; and about the same in breadth. The front of the shop is furnished with folding shutters; commonly consisting of three leaves; one above another: the uppermost of these is turned up in front: the two other leaves, sometimes folded together, are turned down upon the mus'tub'ah, and form an even seat, upon which is spread a mat or carpet, with, perhaps, a cushion or two. Some shops have folding doors, instead of the shutters above described. The shop-keeper generally sits upon the mus'tub'ah; unless he be obliged to retire a little way within his shop, to make room for two or more customers, who mount up on the seat; taking off their shoes before they draw up their feet upon the mat or carpet. To a regular customer, or one who makes any considerable purchase, the shop-keeper generally presents a pipe (unless the former have his own with him, and it be filled and lighted); and he calls or sends to the boy of the nearest coffee-shop, and desires him to bring some coffee, which is served in the same manner as in the house; in small china cups, placed within cups of brass. Not more than two persons can sit conveniently upon the mus'tub'ah of a shop, unless it be more spacious than is commonly the case: but some are three or four feet broad, and the shops to which they belong, five ...