![]()

1

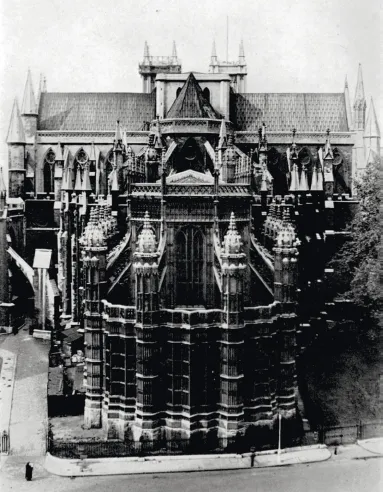

Westminster Abbey: the Crossing

The history and architecture of Westminster Abbey have been studied by many scholars, and one might be forgiven for supposing that we know everything there is to know about this great building. But that is far from being the case, and several key features of the Abbey’s architecture have disappeared, or have never been completed according to the intentions of their designer. The lantern tower, punctuating the point at which the four arms of the church meet (the crossing), is a case in point. It has a long and extraordinarily complex history. What we see emerging from the roof today is merely the stump of a great architectural feature that has never been completed. [1] Neither its date of construction, nor the reason for its abandonment, has been satisfactorily demonstrated. However, there can be little doubt that it was intended to be a worthy successor to the two previous lantern towers that are known to have existed.

No attempt has hitherto been made to write the history of the crossing tower, but in order to understand the historical and architectural significance of the existing lantern – and to assess what might possibly be done in the future to enhance or complete it – it is first necessary to elucidate how the structure arrived at its present form. That is the result of multiple interventions over a period of 950 years.

1 The modern roofscape of Westminster Abbey: aerial view from the south-west. © English Heritage Photo Library

![]()

2

Edward the Confessor’s Crossing Tower and Lantern

The story of the Westminster lantern tower begins much earlier than the present structure, almost one thousand years ago, with Edward the Confessor. Shortly after he ascended the English throne in 1042, he began to rebuild Westminster Abbey in the Romanesque style that was then current in Normandy. At the time of his death in 1066, he had completed the eastern arm, the north and south transepts and half of the nave. A snapshot of Edward’s architectural achievement is preserved in the Bayeux Tapestry. This great embroidery, made by English needleworkers in the 1070s (before 1077), depicts the Abbey church from the north, with much of the north wall and transept cut away to reveal the interior. [2] The dominant feature of the building was the crossing tower, which must have been erected by c. 1060, and stood as high above the ridge-line as the roof did above the ground. The tower was probably square in plan, carried on tall, round-headed arches, and was of two main storeys surmounted by a cupola.1 At the four corners were stair-turrets with conical or pyramidal roofs.2 [3]

2 Edward the Confessor’s abbey church of the 1060s, from the north, as depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry. The crossing was dominated by a great lantern tower. © Ville de Bayeux

3 Birds-eye view reconstruction of Edward’s abbey from the south-west, by Terry Ball, after Richard Gem. WA Lib. Coll.

Great towers housing bells, upper-level chapels and other functions were an integral component of nearly all substantial churches in the eleventh century, although their origins were much earlier (see appendix). These towers could be of multiple stages and their materials comprised stone, timber and various metals: the long-established predilection for such structures is well demonstrated, for example, by the Carolingian monastery of Saint-Riquier in Normandy.3 [111] The Confessor’s tower at Westminster was clearly a stone structure, although the cupola and roofs of the turrets would have been of oak, clad with lead sheets. The leadwork itself was probably ornamented, and there may have been additional embellishments using other metals, such as copper and gold. Although the embroiderers’ detail on the Bayeux Tapestry must not be interpreted too literally, it is by no means unlikely that the prominent striped effect shown on the cupola represents the decorative treatment of the vertical rolls at the junctions of the lead sheets.

While other cruciform churches in late Anglo-Saxon England certainly possessed towers, these were mostly relatively low structures, as at St Mary-in-Castro, Dover. Edward’s tower at Westminster almost certainly represented a level of architectural innovation that was hitherto unseen in the country, and may have borne a resemblance to its closely associated contemporary at Jumièges Abbey in Normandy.

![]()

3

Henry III’s Unfinished Crossing Tower

King Henry III devoted a substantial part of his long reign (1216–72) to the reconstruction of Westminster Abbey in the prevailing Gothic style, which was heavily influenced by contemporary building in France. The Confessor’s church represented Anglo-Norman architecture and liturgical requirements which, after two hundred years, no longer suited Benedictine needs and aspirations. It was impossible to accommodate the contemporary monastic liturgy in the very short, apsidal eastern arm, let alone find space there to create a shrine in honour of St Edward the Confessor. Reconstruction began in 1220 by adding a large Lady Chapel to the eastern arm, thus creating much more liturgical space. The chapel no longer exists, having been superseded in the early sixteenth century by Henry VII’s Lady Chapel [4], but its plan is reconstructible from archaeological evidence.4

The extent to which Henry was the initiator of the Abbey’s reconstruction is uncertain since the work was begun by the monks, but on such a lavish scale that they quickly ran out of funds. In 1240, Henry stepped in to rescue the situation, and in so doing embarked on what was without doubt the most ambitious and expensive church-building project in English history. The Lady Chapel was completed in 1245, after which the demolition and reconstruction of the eastern arm, crossing and transepts of the old building followed. The work progressed at a staggering rate, so that by the mid-1250s the masonry shell of the eastern parts of the church was complete. The master mason (architect) was Henry of Reyns, who was well versed in the vocabulary of the latest French Gothic architecture, but was possibly English by nationality.5 Thus he was presumably the designer of the new crossing tower that replaced King Edward’s.

4 Westminster Abbey from the east in 1936, showing the emphasis placed on octagonal features in Henry III’s original scheme, and further elaborated by Henry VII, whose Lady Chapel appears in the foreground. Almost certainly the square base of the crossing tower was intended to support an impressive octagonal lantern. Henderson 1937

What form of Crossing Tower was envisaged?

It was the norm for major transeptal churches in the early thirteenth century to be provided with a crossing tower (see appendix). Most often in England that took the form of a low, stone-built lantern that did not project very far above the ridge-lines of the four abutting roofs. These lanterns, which were square in plan, had simple lancet windows in the sides, and were often provided with intra-mural passages and newel-stairs housed in turrets at the corners. Moreover, lanterns were open from the church floor upward, although stone vaults or ceilings were often subsequently inserted at the level of the crossing arches, thus eclipsing the lantern effect (as occurred at Wells, Lichfield and Salisbury cathedrals).

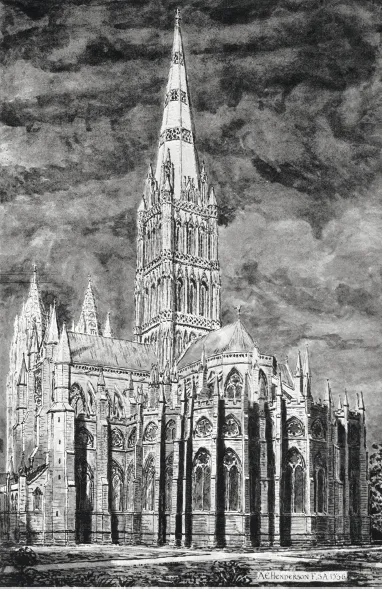

5 Various attempts have been made to reconstruct the appearance of Henry III’s church, and this one by A.E. Henderson shows it from the southeast. The tower and spire – copied from Salisbury Cathedral – are far too elaborate, and the easternmost polygonal apse (Lady Chapel) should project further. Henderson 1937

It is generally assumed that early Gothic lantern towers were topped by a pyramidal lead roof, or a timber and lead spire. In most cases, however, the towers have either been totally rebuilt, or raised in height – often in the fourteenth century – to form full-blown crossing towers, capped with stone or timber spires (e.g. Salisbury and Lichfield cathedrals), thus removing all evidence for the original termination. Almost certainly the roof structure at Westminster would not have been exposed to view from below, being hidden by either a flat ceiling or a timber vault.

The present diminutive lantern, which hardly peeps above the ridge-line at Westminster Abbey, clearly owes nothing apart from its square plan to Henry III or Henry of Reyns. So what were their intentions for the design of the crossing at Westminster? Moreover, how much of their tower was actually constructed, and what happened to it? Unfortunately, there is little solid evidence surviving to demonstrate the form of the structure, and none above the point where it emerged through the roof. However, various strands of architectural, archaeological and historical evidence, bolstered by comparanda from elsewhere, enable us to make both reasoned deductions and educated guesses. We must not, however, be seduced by some older artistic reconstructions which, though exquisite in themselves, are more representative of mid-fourteen...