![]()

1. How Are Businesses and Universities Different? How Are They Similar?

I have no illusion that universities somehow evade the logic of the marketplace. But no other institution is designed so intentionally to provide structures in which free intellectual inquiry can take place.—Lisi Schoenbach

As businesspeople begin their work with academic organizations, the wisest among them proceed with caution to understand the lay of the land. As they gradually become familiar with universities through their roles as trustees or leaders, they come to understand certain key similarities and differences between business and academe. This chapter addresses these similarities and differences. Of course, there are many differences among businesses as well as among colleges and universities, so we will focus on the most widely shared characteristics of each.

How Are Businesses and Universities Different?

GOALS

Businesses have many goals, but the most fundamental is profit. Other goals such as market share, operating efficiency, and talent retention are all in service of long-term profitability. Profit is what allows a business to survive, to invest in growth, and to provide its owners—whether private or public—with a return on their investment. The profit goal is so fundamental to business that its pursuit is used to differentiate between those organizations considered businesses and those that are not—that is, nonprofits.

There is no goal in academic organizations equivalent to profit.1 This is one of the most profound differences between the two types of organizations and, as we will see, the root of many other differences. Colleges and universities are driven by their missions, which are focused on some combination of teaching, research, and public service. An institution’s pursuit of its mission—such as creating new knowledge, educating future leaders, finding cures, disseminating research for the public good, achieving new insight into social change, contributing to economic impact, and so on—characterizes an important driver of higher education.

Despite this focus on mission, no single objective is shared by everyone in the academic institution.2 Each constituency within the academy has a nuanced idea about the relative importance of teaching, research, and service, as well as how each should be measured. In making plans or decisions, “What are we trying to accomplish?” is as important a question as “Will this help us get there?” It is impossible to overstate this fundamental point in understanding the differences between businesses and academic organizations and how little it is understood or appreciated outside the academic sector. Another way of making this point is that academic missions work well at the level of philosophy but are much less effective than profit as a guide to decision-making. This is despite the real, tangible commitment to missions that is easily perceived on college campuses.

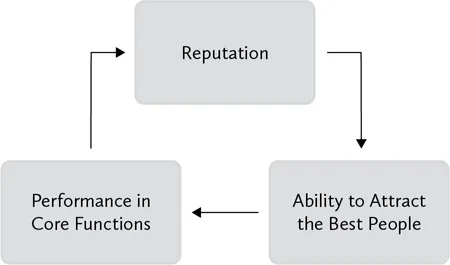

The closest that colleges come to a bottom line is the pursuit of something that could be called prestige, reputation, or quality.3 While quality refers to the actual excellence of one element of the mission (for example, undergraduate education), prestige and reputation are indirect results of quality. The better an academic organization executes any of its core functions, the better its reputation will likely be, all things being equal. But of course, all things are never equal; reputation can, for example, be influenced by strategic communications, in which universities are increasingly investing. And, just as in business, reputations are nearly always lagging indicators of quality. An institution on the way up is probably better than its reputation, while one on the way down is probably worse.

Despite these nuances, reputation and prestige are so important because they strengthen the very things that create quality, particularly students, faculty, and donor support. In this way universities are like their athletic teams—the best are able to recruit the best coaches and athletes and to sustain their dominance—and are the opposite of professional sports, where the worst teams get the best draft picks. In academics, the rich get richer, both literally and figuratively.4

Further emphasizing this difference in goals between businesses and academic organizations is the measurement of profit. Such measurement in the business world is certainly complex, but subject to detailed and strictly enforced accounting practices to ensure that businesses calculate profit in essentially the same way. While there are a few areas in universities with such conventions (such as the calculation of how much funded research a university conducts), the consensus on how to measure elements of university performance and the consequences of violating the agreements that do exist are much weaker than in the private sector.

1.1. Reputation as the cause and outcome of high performance.

Ranking academic institutions is an attempt to reduce the complexity and ambiguity of academic performance to a single number. Rankings are consulted by prospective students, their parents, and alumni. For this reason, academic leaders pay rankings a great deal of attention and strive to make theirs better. U.S. News & World Report’s rankings are the most influential for undergraduate institutions, but there are many others.5 Rankings, like colleges and universities themselves, have increasingly become international and bring some discipline to the performance claims of academic organizations. (An old joke in business schools is that, prior to published rankings, there were fifty schools in the top ten.) And rankings sometimes are used imaginatively by colleges to show how strong they are compared with their competitors (such as “#1 among public liberal arts colleges in the Mid-Atlantic”).

But the promise of rankings to find simplicity beyond the complexity of academic performance is a mirage. Here is why:

1. Publications that rank institutions need to choose from among many elements of college and university performance. If they choose only a few factors, the ranking is necessarily an incomplete representation of the overall quality of the institution. If they choose many, the ranking requires a complex formula whose weights appear arbitrary and probably do not reflect the needs of any specific individual considering a school or college.

2. Whichever elements of performance are incorporated in the rankings, they must be measured, and the measure must be standardized across a wide range of institutions. The choice of measures has a significant and poorly understood impact on the final ranking. For example, think about how to assess the quality of the undergraduate student body. Consider high school grades and test scores? Entrepreneurial potential? Diversity? Character?

3. For many rankings (including those in U.S. News & World Report), a significant component of the formula is created simply by asking people (deans, provosts, presidents) to rate the quality of the institutions being ranked. We have done this ourselves, and the rankings questionnaires include hundreds of institutions, most of which we knew nothing about. This methodology introduces a deeply conservative bias into the rankings and further reinforces the “rich get richer” element of academic performance. Institutions with strong reputations continue to get high rankings of quality simply because of their reputations.

4. In many categories of universities and schools, there are only small differences in performance on measures of various goals. But the use of ordinal scores (literally, rankings) creates the illusion of much greater differences. Four colleges that score 9.75, 9.72, 9.68, and 9.62 on a composite measure that ranges from 1 to 10 will be ranked #1, #2, #3, and #4. (And in some cases, the raw scores are not even made public.) In this way, nuance and accuracy are traded for simplicity and the illusion of clear differences.

5. Colleges and universities simply do not change a great deal from one year to the next. But if the rankings stayed largely the same year after year, the public would lose interest. To combat this danger, rankers periodically update their formulas, leading to movement in the rankings. The extent to which this movement tracks actual changes in quality is anyone’s guess.

6. Finally, and there is no nice way to say this, universities sometimes cheat. Cheating ranges from clever ways of calculating a measure (such as accepting students on a conditional basis so their SAT scores aren’t included in the average, or hiring one’s own students so they can be reported as employed post-graduation) to outright falsification of data.6 In an attempt to discourage cheating, the rankings organizations provide instructions that look a lot like the tax code and require a senior executive to sign off, like the Sarbanes-Oxley requirement for public companies.7

Before we go on to discuss other differences between businesses and universities, it is worth pointing out a final difference in the relationship between profit and reputation (prestige, quality). Businesses of course care about their reputations and go to some lengths to measure and manage them. But reputation is cultivated as a means to long-term profitability and is subordinated to the need to be profitable. In contrast, universities strive to at least break even and sometimes have a small profit (although that is a term you will never see in their financial reports) at the end of the fiscal year. This profit is immediately invested in something intended to enhance the reputation of the college or university. So while reputation is a means to an end (of profit) in business, profit is a means to an end (of reputation) in academics. Dr. Patricia Beeson, professor of economics and provost emeritus at the University of Pittsburgh, takes this point one step further, explaining, “One could argue that universities are motivated by our ability and opportunity to advance and disseminate knowledge, and rankings and prestige are imperfect measures of any institution’s ability to do so. Thus, one might say that profit is a means to an end (of advancing knowledge) in academics.”8

CHAIN OF COMMAND

In business, a clear chain of command proceeds from the board of directors, to the CEO, to his or her direct reports, and then down and throughout the organization to the lowest level. This means that, within broad limits, someone more senior can direct someone more junior to do something, with the expectation that that person will in fact do it. If such a junior employee does not, that employee is putting his or her performance evaluation, and possibly job, in jeopardy. Organizations vary in how explicit they are about this fact. While some businesses try to soften it by using words like “teamwork” and “community,” the chain of command is still fundamental to how they operate. As a consultant friend recently told us, “If the CEO says we are going to do something, we can discuss it, but we all know we are going to do it.”

While there is a chain of command in academics, it is much less definitive than in most businesses. The closest universities come to a business-style chain of command is the relationship between the president and his or her direct reports, who work together in a way not particularly different from those in business. (And, as in business, wise presidents do not simply give orders without consultation and discussion.) University boards seldom order presidents to take a specific action, and when they do, it is generally a sign of trouble. And while presidents and provosts establish policies and budgets that constrain the actions of deans, it is rare for either to give anything like an order to deans, who enjoy considerable autonomy in leading their schools. This softness of command cascades down the ranks, as department heads have wide latitude in how they lead their departments and individual faculty have considerable discretion in how they conduct their teaching and research.

We will discuss the nature of organization and influence in universities in much more detail in chapters 5 and 6, including the concepts of academic freedom, free inquiry, and shared governance. For now, we will conclude by saying that anyone anticipating a business-style chain of command in an academic organization is likely to be disappointed. This is not hypothetical: we have seen deans who come from business wondering why no one did anything when they issued what would be perceived in a corporate setting as a direct order.

SENSE OF URGENCY

Business is known for its focus on the immediate future. The stereotypical businessperson is hurrying, trying to get a number of things done at once, asking subordinates to do things faster, and telling people that “time is money.”9 While this is to some degree a caricature, businesspeople are indeed focused on producing results, now. Business school students are taught that clarity and conciseness are key criteria of effective business communication. The concepts of discounted cash flow and net present value teach us that the timing of financial returns matters, and sooner is better. Customers who are not contacted right away may become someone else’s customers. Deals that are not closed quickly may never happen.10

This is particularly true in publicly owned companies, where quarterly profits are dissected relative to their competitors, previous quarters, signals from the chief financial officer, and so on. This environment has created a constant sense of urgency in many businesspeople, as well as an industry devoted to addressing stress, work-life balance, and burnout.

While some aspects of academe are very much “on the clock,” such as turning in grades or submitting grant proposals, most colleges and universities do not operate with the same short-term focus and sense of urgency as business. No doubt this is related to our discussion above about the absence of consensus on goals. Many high-level goals (for example, the quality of the incoming class or the percentage of graduates who find jobs) can be measured only annually. And many elements of university work, especially research, simply take a long time. As we will discuss in chapter 5, it can take five years or more in a PhD program to become a professor.

Another way to understand this gap in perspectives between the worlds of business and academics is to consider the rates of failure in the two sectors: business failure is routine, while university failure is very unusual. As Robert M. Hendrickson and his colleagues point out, “None of the original 30 industries listed on the Dow Jones Industrial Average in 1928 are on the list today, and many no longer exist at all, yet all 30 of the top universities in the country in 1928 still exist, and most of them would still be considered among the best.”11 At the other end of the scale, a recent study of “invisible colleges” (small, private, nonselective colleges) found that in the forty years between 1972 and 2012, only 16 percent of these potentially fragile institutions closed.12

When the president of Sweet Briar College in Virginia announced in 2015 that it was going to close due to serious financial problems, the event was breathlessly covered by the higher education press and even the national media.13 In the end, however, Sweet Briar remained open. Consider this: even a college whose president wanted it to close didn’t close. In summary, busines...