- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

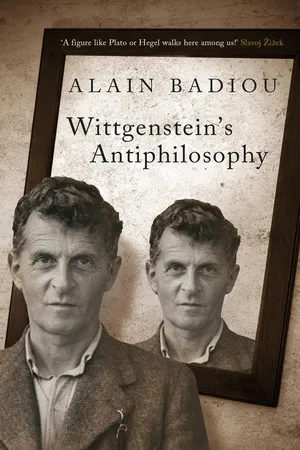

Wittgenstein's Antiphilosophy

About this book

Alain Badiou takes on the standard bearer of the "linguistic turn" in modern philosophy and anatomizes the "antiphilosophy" of Ludwig Wittgenstein. In the course of his interrogation of Wittgenstein's thinking, Badiou refines his own definitions of the universal truths that govern his work. Bruno Bosteels's introduction argues that a continuing dialogue with Wittgenstein is inescapable for contemporary philosophy.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Wittgenstein’s Antiphilosophy

It is certainly not unreasonable to hold that Wittgenstein has been a hero of our time. But only if we rigorously examine of which cause he has been the hero, how he held up this cause, and how he lost himself in the impossibility—poorly masked by a kind of speculative insolence—of the unprecedented act whose promise he cherished.

1

In November 1914, Wittgenstein is at war. He has already seen the line of fire. His activity as a soldier is strangely attuned to his maxim according to which it is vain to produce philosophical propositions, given that what matters is “the clarification of propositions” (4.112). Let us translate this into military language: the point is not to shoot but to clarify the shot. And so Wittgenstein, who will later become an “observer” to correct the trajectory followed by the bombs, takes care of a searchlight on board a gunboat. His base is in Krakow. Here he finds the crucial final works of Nietzsche, the ones from 1888, above all The Anti-Christ. At this time he notes in his journal: “I am strongly affected by his hostility against Christianity. Because his writings too have some [part of] truth in them.”1

Our first question will be the following: what is this “part of truth” whose existence Wittgenstein recognizes in the imprecations of Dionysus against the Crucified? And our second one: what can Wittgenstein mean by Christianity if despite this “part” he feels deeply hurt by the anti-priest legislation of the fury from Turin? These are decisive questions if we consider that Nietzsche and Wittgenstein, each in his own turn, have set the tone for the twentieth century in terms of a certain form of philosophical contempt for philosophy.

2

What Nietzsche and Wittgenstein share in common I will designate with a term introduced by the third great and fascinated detractor of philosophy from the last century, Jacques Lacan: antiphilosophy. The word is out. But not as an isolated one, because if it is true that the elucidation of this term defines the stakes of this whole text for which Wittgenstein will be our teacher, we are not for this reason free of the burden temporarily to fix the boundaries of its power.

Antiphilosophy, from its origins (I would say from Heraclitus, who is as much the antiphilosopher to Parmenides as Pascal is to Descartes), can be recognized by three joint operations:

1. A linguistic, logical, genealogical critique of the statements of philosophy; a deposing of the category of truth; an unraveling of the pretensions of philosophy to constitute itself as theory. In order to do so, antiphilosophy often delves into the resources that sophistics exploit as well. In the case of Nietzsche, this operation bears the name “overturning of all values,” struggle against the Plato-disease, combatant grammar of signs and types.

2. The recognition of the fact that philosophy, in the final instance, cannot be reduced to its discursive appearance, its propositions, its fallacious theoretical exterior. Philosophy is an act, of which the fabulations about “truth” are the clothing, the propaganda, the lies. In the case of Nietzsche, it is a question of discerning behind these ornaments the powerful figure of the priest, the active organizer of reactive forces, the one who profits from nihilism, the captain who enjoys resentment.

3. The appeal made, against the philosophical act, to another, radically new act, which will either be called philosophical as well, thereby creating an equivocation (through which the “little philosopher” consents with delight to the spit that covers his body), or else, more honestly, supraphilosophical or even aphilosophical. This act without precedent destroys the philosophical act, all the while clarifying its noxious character. It overcomes it affirmatively. In Nietzsche’s case, this act is archipolitical in nature, and its directive says: “To break in two the history of the world.”2

Can we recognize these three operations in Wittgenstein’s oeuvre? By the latter we will understand the only text that he deemed worthy of public exposure during his lifetime: the Tractatus. The rest, all the rest, it is convenient not to grant it anything more (and this is all the better, considering everything that gradually crumbles therein) than the status of an immanent gloss, a personal Talmud. The answer is surely positive:

1. Philosophy is divested of all theoretical pretensions, not because it would be an embroidery of approximations and errors—which would still be conceding too much to it—but because its very intention is vitiated: “Most of the propositions and questions to be found in philosophical works are not false but nonsensical” (4.003). It is typical of antiphilosophy that its purpose is never to discuss any philosophical theses (like the philosophers worthy of that name who refute their predecessors or their contemporaries), since to do so it would have to share its norms (for instance, those of the true and the false). What the antiphilosopher wants to do is to situate the philosophical desire in its entirety in the register of the erroneous and the harmful. The metaphor of sickness is never absent from this plan, and it certainly comes through when Wittgenstein speaks of the “nonsensical.” Insofar as “nonsensical” means “deprived of sense,” it follows that philosophy is not even a form of thinking. The definition of thought is indeed precise: “A thought is a proposition with a sense” (4).

Philosophy, then, is a non-thought. Moreover—this is a subtle but also crucial point—it is not an affirmative non-thought, which would cross the limits of the proposition endowed with sense in order to seize upon a real unsayable. Philosophy is a sick and regressive non-thought, because it pretends to present the nonsense that is proper to it within a propositional and theoretical register. The philosophical sickness appears when nonsense exhibits itself as sense, when non-thought imagines itself to be a thought. Hence, philosophy must not be refuted, as if it were a false thought; it must be judged and condemned as a fault of non-thought, the gravest of faults: to inscribe itself nonsensically into the protocols (propositions and theories) reserved for thought alone. Philosophy, with regard to the eminent final dignity of affirmative non-thought (that of an act that crosses the barrier of sense), is guilty.

2. The fact that the essence of philosophy does not reside in its sick and fallacious appearance in the form of propositions and theories, but that it is first and foremost on the order of the act, is something that Wittgenstein proclaims, in 4.112, not without letting an equivocation surface between inherited philosophy, which is nonsensical, and his own antiphilosophy: “Philosophy is not a body of doctrine but an activity.”

The general value of this assertion nonetheless becomes clear if we relate the desire of philosophy to the activity of the sciences. Everyone will agree that philosophy is concerned with the final ends, with what is higher, with what matters to the life of human beings. However, none of this is of any concern to the theoretical activity properly speaking, which takes the form of propositions (endowed with a sense, or even better, true propositions, that is to say, science: “The totality of true propositions is the whole of natural science” [4.11]). Perhaps it is regrettable (especially to those who believed that they could find a positivist in Wittgenstein, or even an analytical and rationalist philosopher), but it is beyond doubt that “propositions can express nothing that is higher” (6.42). And better yet: “We feel that even when all possible scientific questions have been answered, the problems of life remain completely untouched” (6.52). In the general aspiration that induces its existence, philosophy, devoted as it is to the “problems of life,” is intrinsically different from any scientific or theoretical figure. It is subtracted from the authority of propositions and of sense, and for this reason destined at the same time to take the form of the act. Simply put, there will be two types of such an act. One, which is infrascientific and nonsensical because it attempts to bend non-thought by force into the theoretical proposition, is the philosophical sickness proper. The other, suprascientific, silently affirms non-thought as a “touching” of the real. It is the authentic “philosophy,” which is a conquest of antiphilosophy.

3. It is thus necessary to come to the announcement of an act of a new type, which simultaneously overcomes the philosophical sickness, undoes the regressive act by which one searches nonsensically to incarnate the “problems of life” in theoretical propositions, and affirms, this time beyond science, the rights of the real. In order better to distinguish this act from all that is forced and maniacal about the philosophical act, Wittgenstein rather describes it as an element, as that in which the authentic non-thought dwells. But already Nietzsche proceeded in the same way in order to transmit to us the powers of the Great Noon, of “saintly affirmation”: one did not pass through the hallways of the will in its narrow, programmatic, and moral sense; one was “transported” by radiant metaphors. Wittgenstein, too, is condemned to metaphor, because the act must install an active non-thought beyond all meaningful propositions, beyond all thought, which also means beyond all science. The one he chooses articulates an artistic provenance (visibility, showing) with a religious one (mysticism): “There are, indeed, things that cannot be put into words. They make themselves manifest. They are what is mystical” (6.522).

The antiphilosophical act consists in letting what there is show itself, insofar as “what there is” is precisely that which no true proposition can say. If Wittgenstein’s antiphilosophical act can legitimately be declared archiaesthetic, it is because this “letting-be” has the non-propositional form of pure showing, of clarity, and because such clarity befalls the unsayable only in the thoughtless form of an oeuvre (music certainly being the paradigm for such donation for Wittgenstein). I say archiaesthetic because it is not a question of substituting art for philosophy either. It is a question of bringing into scientific and propositional activity the principle of a kind of clarity whose (mystical) element is beyond this activity and the real paradigm of which is art. It is thus a question of firmly establishing the laws of the sayable (of the thinkable), in order for the unsayable (the unthinkable, which is ultimately given only in the form of art) to be situated as the “upper limit” of the sayable itself: “Philosophy [that is, antiphilosophy] must set limits to what can be thought; and, in doing so, to what cannot be thought” (4.114). And: “It will signify what cannot be said, by presenting clearly what can be said” (4.115). Here we observe that the antiphilosophical act comes down to tracing a line of demarcation, as Althusser would have said in the wake of Lenin. And it is very well possible that Althusser’s project, under the name of “materialist philosophy,” came close to twentieth-century antiphilosophy. The difference being that for Althusser it was the proximity of revolutionary politics, under the partisan name of “taking sides,” that silently educated the clarity induced by this separating act, while for Wittgenstein, under the name of the “mystical element,” it is rather a mixture of the Gospels and of classical music.

In any case, there can be no doubt that the three constitutive operations of all antiphilosophy can be retrieved in Wittgenstein, which does justice to his discovery of a “part of truth” in Nietzsche’s work, his greatest predecessor in this matter.

This part of truth then enters into a dialectic with the obvious differences:

• To the genealogical ruin of philosophical statements in Nietzsche, to the evidencing of types of power supporting them, and thus to an analytic of the lie as a figure of vital impulse, there corresponds in Wittgenstein the evidencing of an absurdity, which entails the forcing of the linguistic sphere of sense by nonsense. For Nietzsche, metaphysics is will to nothingness; for Wittgenstein, it is the nothingness of sense exhibited as sense. The sickness bears a name: for Nietzsche, it is nihilism; for Wittgenstein, perhaps worse, gassing or babbling.

• For Nietzsche, the hidden philosophical act is the exercise of the typological power of the priest. For Wittgenstein, it is the erasure of the line of partitioning between the sayable and the unsayable, between the thinkable and the unthinkable; it is the will to non-clarity about limits. It is thus also, and here Nietzsche would agree, the blind, properly unchained exercise of a language delivered over to the dream of not being interrupted by any rule, nor limited by any difference.

• For Nietzsche, the announced act is archipolitical, since the pure affirmation is equally the pure destruction of the earthly power of the priest. For Wittgenstein, it is archiaesthetic, since the principle (which is itself unsayable) of all clarity regarding the limits of the sayable proceeds from the possibility of gaining access to the artistic paradigms of pure showing, which also means access to the saintly life as inner beauty: “Ethics and aesthetics are one and the same” (6.421). And, better yet, this belated, almost testamentary declaration (after many abandonments and wanderings what is essential comes back): “I think I summed up my attitude to philosophy when I said: philosophy ought really to be written only as a poetic composition.”3

3

Here, though, is what Nietzsche and Wittgenstein do not share: the second is “strongly affected” by the first’s hostility toward Christianity.

The connection of Christianity to modern antiphilosophy has a long history. We can easily draw up the list of antiphilosophers of strong caliber: Pascal, Rousseau, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, and Lacan. What catches the eye is that four of these stand in an essential relation to Christianity: Pascal, Rousseau, Kierkegaard, and Wittgenstein; that Nietzsche’s enraged hatred is itself at least as strong a bond as love, which alone explains the fact that the Nietzsche of the “letters of madness” can sign indifferently as “Dionysus” or as “the Crucified”; that Lacan, the only true rationalist of the group, but also the one who completes the cycle of modern antiphilosophy, nonetheless holds Christianity to be decisive for the constitution of the subject of science, and that it is in vain that we hope to untie ourselves from the religious theme, which is structural in nature.

The true question consists in knowing what “Christianity” is the name of in Wittgenstein’s antiphilosophical arrangement. It is certainly not the name of an established, or instituted, religion. This is, moreover, never the case, not even for Pascal, whose hatred of the Jesuits is clearly aimed at everything in religion that takes the form of a reality. The “religion” of antiphilosophers is a material they grab hold of at a distance from philosophy so as to name the singularity of their act.

Wittgenstein’s references to Christianity are first of all literary and Russian: Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. The Gospel itself is grasped as such an oeuvre, the possible example of a principle of clarity as to what the saintly life, that is, the beautiful life, can be.

In truth, “Christianity” names a clarification of the sense of life, which is also the sense of the world (since, as per 5.63, “I am my world”). It can then be distributed along two axes:

1. Objectively, we know that the sense of the world does not belong to what can be said, which, in the form of the proposition or of theory, is only scientific. Thus the sense or meaning of the world, situated out of reach of the sayable, ca...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Translator’s Introduction

- Preface

- 1. Wittgenstein’s Antiphilosophy

- 2. The Languages of Wittgenstein

- Notes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Wittgenstein's Antiphilosophy by Alain Badiou, Bruno Bosteels in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophie & Philosophen. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.