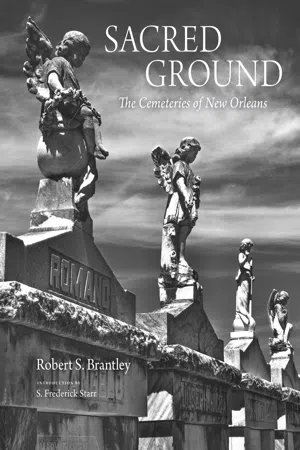

![]()

“Silence” pediment; tomb of Iberian Society, St. Louis Cemetery #2, Square 2

![]()

Silent Sentinels Against Time

SILENCE.

A simple word carved into the pedestal atop a large society tomb in St. Louis Cemetery #2, Square 2. Was the word meant for the living or the dead? In religions around the world, silence is revered as a meditative tool to come closer to God, the creator, and to all living things. Silence allows us to delve deep within ourselves and experience the thread that runs through all things and joins all creation as one. The Buddhist and Zen masters call it enlightenment; Christians, the love and peace of God. We call out by our silence to the One who hears all.

When St. Louis Cemetery #2 was first founded, it was a place of quiet and peace. There were no automobiles, ringing cell phones, airplanes, or interstate highways. By the time I saw that word silence carved deeply into white marble, I was struck by all the noise about me. Now the cemetery lies next to a raised freeway that delivers constant noise and distraction. But if you listen and concentrate, quiet again comes to the cemetery— your mind simply eliminates the background noise and slips into realms of silence and the dead. As you wander about, you begin to read the names and inscriptions on the tombs. Each name carved into the marble, slate, granite, or plaster represents a life lived; with the exception of the famous, we know little if anything about them. These people lived in another time; they are not like us nor we them. We each choose a path, each live our lives and hope to find love along the way. No one is guaranteed anything but a beginning and an end. It is how we live that matters.

Whether old and simple or relatively new and grand, each monument is a visual feast. Attached to crumbling brick tombs, magnificent carved tablets with names mostly eroded by wind, rain, and time seem to be sentinels staring back at us. Next to them may stand a large mausoleum of granite and marble in near-perfect condition. Each is a resting place of people and their dreams, whether fulfilled or not. The wealthy and the poor, the powerful and powerless, owners and slaves— all have shared the same fate and all are finally equal.

As an architectural photographer and researcher, I was initially attracted by the architecture of these small cities, with their rows and aisles like streets in any neighborhood. This evolved into wondering, puzzling over what these people were like. What were their favorite foods, books, pleasures, games, songs—all those things and events that composed their daily lives? I could no longer look only at the structures, no matter how majestic or simple, without thinking of the people interred there. I knew that there was no possible way I could answer these questions or the other thousand that came to mind. The full stories would always remain a mystery. What I could do was simple: point a camera and release the shutter.

Tomb of Jean Baptiste Dupeire, St. Louis Cemetery #2, Square 2

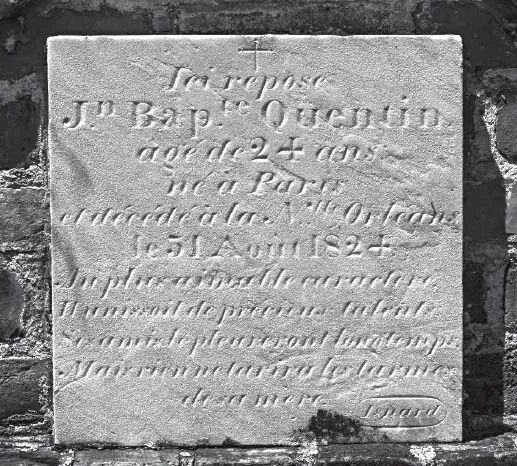

Jean Baptiste Quentin died at twenty-four in 1824. His tablet extols his virtues and tells of a life cut short. Wall vault tablet of Jean Baptiste Quentin, St. Louis Cemetery #2, Square 2

I began photographing cemeteries little by little. In early 1980 the pioneer preservationist and founder of Save Our Cemeteries, Mary Lou Christovich, asked me to join her on Saturday mornings to clean cemeteries. I began to see the deterioration firsthand as we cut trees out of the top of tombs, pulled weeds, and raked away debris. Along the way she became a close friend and mentor. I do not remember how many Saturday mornings we spent getting completely covered in dirt and grime, but I have never lost the sense of accomplishment in doing something for someone I have never known who has been long deceased. Mary Lou gave me a gift I cannot repay, but I hope that the work in this volume will speak for me.

In 1981 I was asked to head an inventory of historic cemeteries in New Orleans. The project began modestly, with St. Louis #1 and #2 chosen for study. It soon gained a momentum of its own and expanded into several other city and private cemeteries. Each tomb was described, and anything written on the closure tablets was transcribed exactly on a card, with care to match the upper- and lowercase lettering and punctuation. The tombs were then photographed. All this information is now housed at the Historic New Orleans Collection, the originator of the project. It covers thousands of tombs and wall vaults. Sadly, the photographs and written descriptions are now testimony to how much has since been broken and stolen, including wrought- and cast-iron fences and gates, marble vases, urns, crosses, and, in a few cases, entire tablets. Time has taken a serious toll on the cemeteries. They have suffered damage from hurricanes, hailstorms, freeze expansion within marble, neglect, theft, and vandalism. These monuments to the history of the people of this city are fragile and in need of utmost care and preservation.

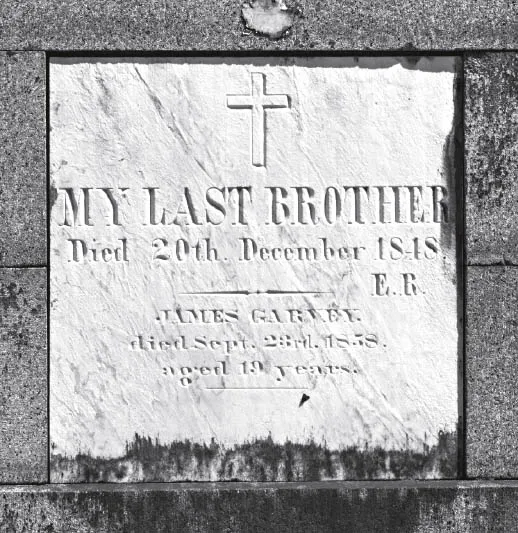

As people wander about these cemeteries reading names and dates, they sometimes come across heart-rending inscriptions—emotional pleas from another age. They are messages in a bottle sent floating on time, awaiting the right person to read them. Perhaps to some passersby, the words on these tablets cause a swell of tears because they know all too well the emotions behind the epitaphs. One man tried to express the agonizing loss of his beloved wife with “All the Beauty that Could Die.” A younger brother wrote a poignant statement after all his brothers had died; it is simplicity itself: “My Last Brother.” One epitaph seems to convey the last words of a ten-year-old child heard by his mother shortly before he drowned, “Mother, I’m going out to play.” A small, simple tombstone bears only two words: “Our Babies.” There are thousands of examples such as these—we try to call back to them with compassionate understanding, no matter how limited. The thread of humanity connects us to those who have gone before; these people interred are teachers of life, for they all knew great suffering and triumphed over it.

Tomb of Delachaise and Livaudais families, St. Louis Cemetery #2, Square 2

Tomb of Mark Walton family, Cypress Grove Cemetery

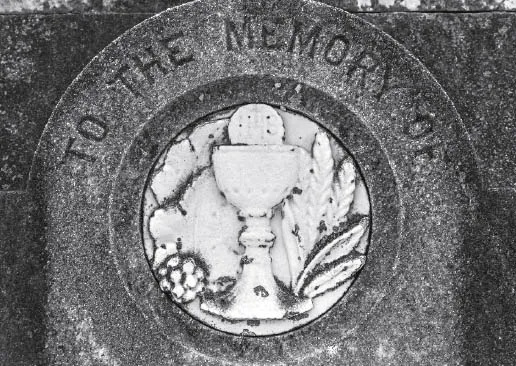

Walking through the aisles of the cemeteries, one notices features carved into the stone accenting the names and dates. Are they mere decorative ornamentations, or are they meant to convey meaning and events? They can be both. From the rather common variations of the weeping willow to the rare chalice with Host and the insignia of the Knights of Pythias, each communicates information or events about the deceased. We have only to stop and look at these symbols representing organizations, professions, talents, religious beliefs, or the pain of the surviving friends and family. Who cannot be stirred by the Weeping Willow cascading over an altar with a man bent over it in convulsive tears, longing for his lost love? These symbols are meant to tell stories about men and women who can no longer speak for themselves.

In my quest over the years to photograph and document tombs and their appurtenances, my fascination has grown about the people within. I would look at the names—some famous or notorious but mostly unknown to me. These individuals, nameless faces in old photographs, built the city I love so much. They were born and lived their lives quietly without conquering nations or writing great passages of literature; instead, they lived each day as best as they were able, caring for their loved ones and suffering their losses. These were people I wish I had known—it matters not to me their skin color, affiliations, accomplishments, religious denomination, or worldly possessions. I want to know the how and the why of their lives. The tombs kept drawing me closer to these people. I cannot laugh with them, console them, celebrate with them, or even simply take a walk with them. Instead, I have chosen twenty-one people from tablets and researched them. In all honesty, I do not know if the choices were random or if these individuals were calling out to be remembered. I have tried to write each story from the information I could find. These stories are not complete by anyone’s imagination, but they are an attempt to make these New Orleans citizens live again, to be appreciated and, most important, remembered.

Weeping willow symbolizing mourning (especially for a spouse), and a sleeping lamb representing peace, innocence, and sacrifice; headstone of Catherine Lyons, St. Patrick’s Cemetery #2

Detail; tomb of James Garvey, St. Patrick’s Cemetery #2

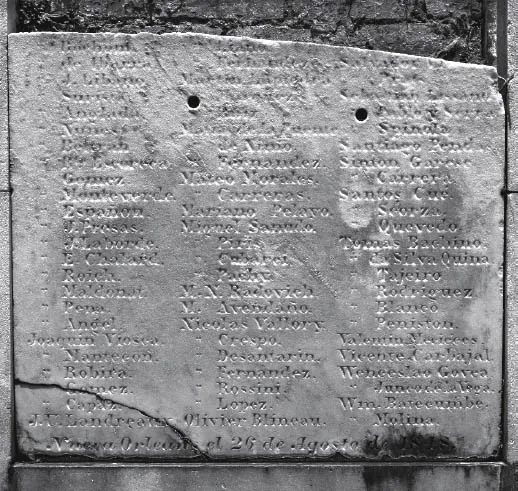

Membership list; tomb of the Iberian Society, St. Louis Cemetery #2, Square 2

Chalice and Host detail; monument of Reverend Father René M. J. Vallée, Carrollton Cemetery #2

![]()

Nicolas Mioton

1791–1834

Within the labyrinth of tombs that is St. Louis Cemetery #1 stands a three-tier stucco-covered tomb known as No. 440 in the South Quadrant. It bears a simple inscription:

NICOLAS MIOTON 19 FÉVRIER 1834

Nicholas Mioton married Anne Emilie Daram, who went by Emilie, in 1810. The onset in June 1812 of war between the United States and Great Britain slowed New Orleans’s economy but did not cripple it until late 1814, when a large troop contingent from the British navy, fresh from the Napoleonic Wars, drove westward from Lake Borgne to capture New Orleans and the vast lands of the Louisiana Purchase. General Andrew Jackson arrived in the city on December 1 and began rallying the citizenry to face the inevitable. War was on their doorsteps.

Mioton, twenty-three, along with over a thousand others—including bankers, farmers, doctors, shopkeepers, slaves, and Native Americans—took up arms to protect their families and city. Land skirmishes began on the night of December 23 and continued sporadically over the next several weeks. Fortifications were dug below the city, lines formed, and the wait began. Mioton was a corporal under Major Jean Baptiste Plauché of the Orleans Battalion of Volunteers Foot Dragoons. By Saturday night, January 7, he was a veteran and found himself assigned to the far right end of the line. Heavily outnumbered, the Americans stood their ground. Before dawn the following morning, under cover of a heavy fog and a withering barrage of British rockets and artillery, Mioton would see the heaviest fighting, yet his ragtag army fought with distinction and dealt the British a humiliating defeat. The British never again threatened the United States.

Emilie and Nicolas Mioton’s first child, Celina, had been born in 1812. After the war, Nicolas’s early business life was not recorded until 1822, when he was a confectioner at 64 Chartres Street, near Bienville. That year, he bought a building nearby, at 136 Chartres, and moved his family and business there. His confectionery was on the first floor, and the family lived upstairs, where they settled into a quiet life with their five children. In 1831 Mioton bought a parcel of land about two-and-a-half miles below the city, facing the river, where the family moved before 1834. The confectionery business remained in town.

Seventeen-year-old Celina married Robert Stephen Hill, a tailor, in the spring of 1829; her sister Aline married Adolph Tremé, a planter, in 1832. The following year, Mioton gave each sister $2,000 (about $60,000 today). Celina gave the money to her husband to open a tailoring establishment, whereupon he traveled to Europe to procure cloth and other articles. During his absence Celina lived with her parents, close to the pregnant Aline Tremé’s plantation. Frequent visits to her sister, brother-in-law Adolph, and his brother, Edouard, both veterans with Mioton in the late war, gave Celina great comfort. Edouard and Adolph were sons of Claude Tremé, who had developed the suburb (or “Faubourg”) just behind the French Quarter that is known today as Faubourg Tremé.

Celina and Edouard indulged in an affair that left her pregnant. When her husband returned in November 1833, he discovered his wife’s infidelity. Raging, he demanded to know the man’s name. When she finally confessed, her father went to see Edouard, asking him to honor his actions and marry his daughter if a divorce could be arranged. (In Louisiana at the time, adultery was one of the few ways a divorce could be granted.) Edouard agreed, and the divorce was hastily arranged and finalized on January 15, 1834. Edouard Tremé’s name was scratched off the divorce documents and did not appear in the newspapers, speaking to the influence of Nicolas Mioton. Yet, when the divorce document is examined closely, traces of Tremé’s name remain visible.

The divorce final, Tremé surprised Celina’s father by turning on his promise and saying there would be no wedding. Mioton left him with an ultimatum: he had fourteen days to decide. If his daughter could not be satisfied with marriage, Nicolas Mioton w...