eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

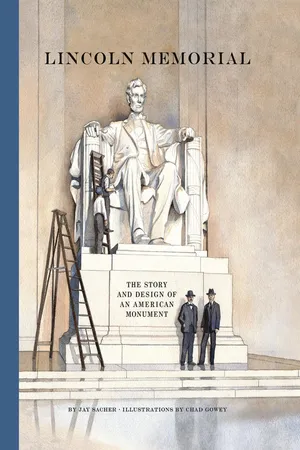

Lincoln Memorial

The Story and Design of an American Monument

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

About this book

Though Abraham Lincoln remains one of the most beloved figures in American history and millions of people visit the Lincoln Memorial each year, few are familiar with the intriguing stories behind this national monument. In authoritative yet friendly text and handsome watercolor illustrations, this volume reveals fascinating facts about the monument's design and construction, historic events that took place there, and insights into the role this elegant edifice has played in the creation of a national identity. From 19th-century political infighting to Martin Luther King Jr. and beyond, this is a celebration of an iconic American and a famous memorial— and the ideal gift for architecture lovers and history buffs.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Lincoln Memorial by Jay Sacher, Chad Gowey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

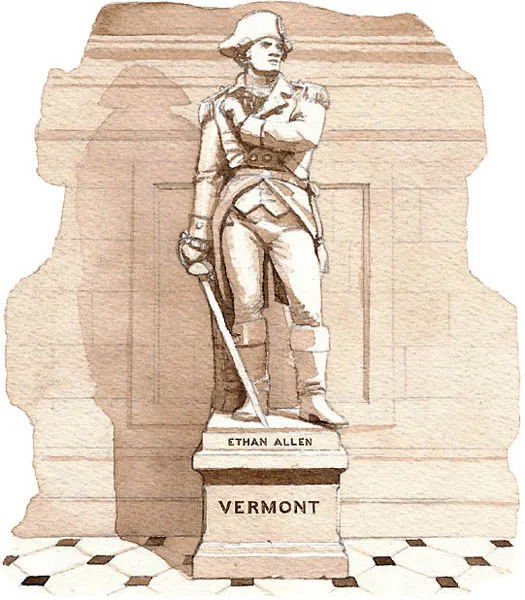

THE CITY BEAUTIFUL AND THE BIRTH OF THE AMERICAN MONUMENT

On July 2, 1864, as the Civil War continued its bloody path across the divided union, President Abraham Lincoln signed legislation authorizing the transformation of the “Old Hall” of the House of Representatives, which had been vacated by the Senate some years before for more spacious quarters, into the National Statuary Hall. Each of the Union’s states were invited to “provide and furnish statues, in marble or bronze, not exceeding two in number for each state, of deceased persons who have been citizens thereof, and illustrious for their historic renown or for their distinguished civic or military services such as each State may deem worthy of this national commemoration.”

In his career, Lincoln certainly signed more important legislation of lasting moral value and historical significance, but there is something telling in the symbolic act of creating a shrine that required each state’s intimate involvement in the creation of a single whole, especially at a time when the nation was waging a war with itself. It was a sign of things to come, both of the physical reunification of the nation and of the philosophic centralization of the idea of America. Ever a youthful country, in the 1860s the United States was a mere infant. Not yet a century old, the stories it was attempting to tell about itself were still fragmented and emerging; the symbology of the national identity was still green and in many ways formless.

One of Vermont’s statues in the National Statuary Hall

Union and the Confederate flags, 1864

Consider that in 1864, Mark Twain was still working as a reporter in the gold-crazy West, his great American novels, including Huckleberry Finn, the book from which Ernest Hemingway famously noted all modern “American” literature is birthed, would not be finished until 1883. “The Star Spangled Banner” would not be officially recognized as the country’s national anthem until 1931, with various contenders, such as “Hail Columbia,” regionally holding their own throughout the 1800s. Even the very names of the states and emerging territories of the nation remained in flux. Arizona was recognized (surprisingly) by the Confederate States of America in 1861 (over such other choices as “Pimeria” and “Gadsonia”), and Nevada was ushered into existence (over the name “Humboldt,” which was preferred by the prospectors who called the state their home) by the United States in 1864. And of course, all the many towns and cities in the nation (including a state capital) named Lincoln were yet to be called thus (all except for one: in 1853, Lincoln, then a lawyer in Springfield, Illinois, was hired to help prepare legal documents for surveyors laying out a site in a rural part of his state. The surveyors proceeded to name the town for him in gratitude. Lincoln is said to have genially chided them, observing that he “never knew anything named Lincoln that amounted to much”).

As the American “story” began to coalesce in the in the latter half of the nineteenth century, so too did the government itself shift toward a more centralized identity. Previously, politicians and thinkers spoke of “these United States”—as the phrase was written in the Declaration of Independence—echoing the earlier notion of a loose confederation, to “the United States,” a single body, a Union, rescued and restored from bloodshed and sin by a martyred president. The necessities of the Reconstruction, various economic crises, and the emerging industrialized culture all helped herald in the new, stronger federal government, but it was (and remains) an ongoing ideological battle. As discussed in more detail later, that tug of war over the nature of American government was at the center of the long delay in approving and building a national memorial to Abraham Lincoln, but no matter where individuals assigned their ideological allegiances, it was clear that by the 1870s, a new understanding of American identity was emerging.

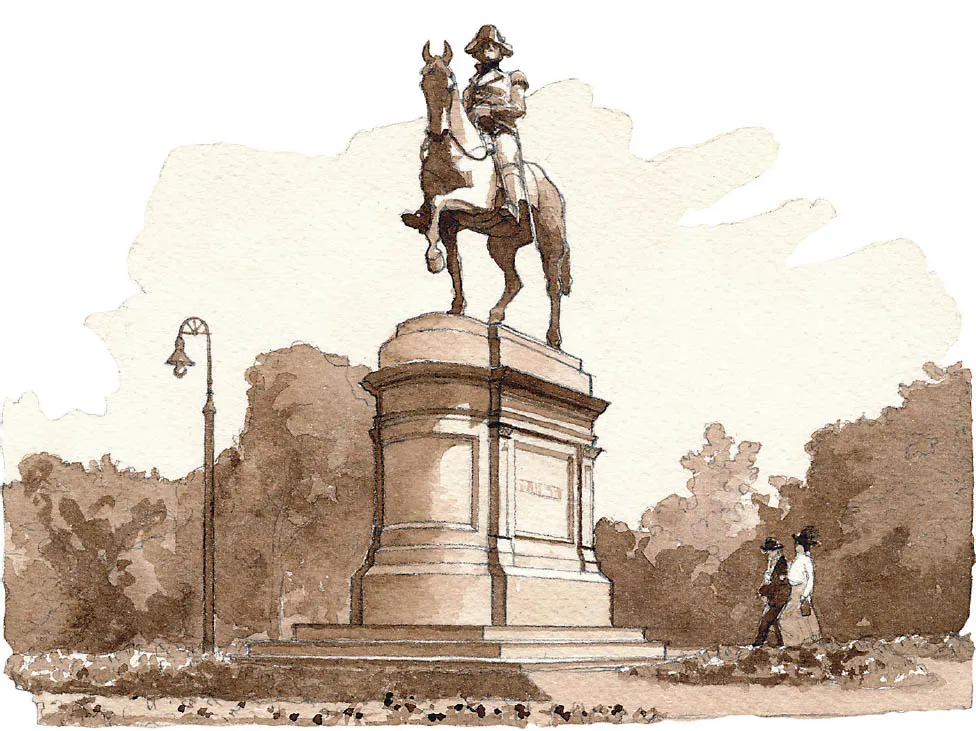

Before that decade, civic monuments to national heroes in the United States were not unheard of, but they were rare. There were well-known memorial statues in three major cities—New York, Washington, and Boston—all of George Washington on horseback. Washington was the most popular of subjects, but slowly, a wider pantheon of heroes began to emerge. Clark Mills’s statue of Washington in the capitol was dedicated in 1860; by 1914, Washington boasted statues and memorials to Benjamin Franklin, John Witherspoon, Edmund Burke, the Marquis de Lafayette, Nathaniel Greene, General Casimir Pulaski, Brigadier General Thaddeus Kosciuszko, John Paul Jones, and Captain Nathan Hale, among others. New York’s Statue of Liberty was dedicated in 1886, and most of that city’s major classical monuments were born in the same era and into the early years of the twentieth century. And so it was in the other major American cities: Thomas Ball’s bronze of Washington in Boston’s Public Garden was dedicated in 1869, and Philadelphia’s statue of Commodore John Barry at Independence Hall was dedicated in 1907.

Thomas Ball’s bronze statue of George Washington in the Boston Public Garden

While the national identity had indeed shifted, there was more at work in this explosion of classical sculpture in the New World. America in the first half of the nineteenth century remained a frontier nation. There were no parallels to the classical tradition of European sculpture and art. The skilled-craftsman carvers of Florence and Rome, so adept at transferring plaster designs to marble, had no equals across the Atlantic. Even the infrastructure for quarrying marble did not exist on the scale that it did in Europe. American artists of the era went to Europe for education, but they often stayed in Italy to work. These early American craftsmen, such as Horatio Greenough and Thomas Crawford, sold their sprightly marble fauns and stern Roman busts for display in the drawing rooms of the New World’s elite. Around the midcentury mark, American sculptors also began to flock to Paris to study the more delicate clay work necessary for casting successful bronze sculptures. The pool of talented American ex-pats was growing and developing its own tradition; now something was needed to call them home. The 1864 authorization of the National Statuary Hall provided the perfect proving ground for a growing class of artisans eager for a genuine American voice, one that fit in well with a revived interest in civic monuments, and that would lead directly, across the decades, to the Lincoln Memorial.

Rising concurrently with the increased skill of American-born artisans was a larger idealistic notion about the American city and its architecture, one that coalesced toward the close of the century as a school of thought called the “City Beautiful.” The movement was born from, and closely related to, the Beaux Arts architectural style that influenced the American cityscape throughout the Gilded Age of the nineteenth century. Simply put, the Beaux Arts style refers to a bold neoclassical approach to architecture that was taught at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Its influence in America was both direct (as students returned from Paris to build in America) and indirect as the style caught on throughout the nation. Many now-historic buildings, such as the New York Public Library and Chicago’s Union Station, are prime examples of the magnitude and grand ambition of the Beaux Arts style.

The White City Chicago Columbian Exposition, 1893

The City Beautiful movement married the aesthetic of the Beaux Arts movement to a struggle to better both the visage of the city and the spirit of its inhabitants through compelling architecture; wide, pleasant thoroughfares; and artistically embellished public space and parklands. The stated goal was not to simply make a city more pleasing to the eye, but to enlighten and enrich its residents and to use the newfound wealth of the industrial era to build a better life for all. One of the City Beautiful’s major proponents, Charles Mulford Robinson, considered the movement to be “the latest step in the course of civic evolution. The flowering of great cities into beauty is the sure and ultimate phase of a progressive development.” Of particular interest, he noted the power of political and state-sponsored monuments. “For where political life is ardent, the civic consciousness is strong; the impulse toward creative representation is fervent; and state, government, the ideals of parties, are no longer abstractions, but are concrete things to be loved or hated, worked for, and done visible homage to.”

The movement’s genesis was thanks in a large part to the Chicago architect Daniel Burnham, who along with Fredrick Law Olmstead (the designer of New York’s Central Park) created a living example of the City Beautiful for the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893. The fairgrounds, known as “the White City” (the buildings’ facades were finished with a gleaming white stucco), covered six hundred acres with stunning neoclassical architecture, designed in concordance with axial pathways and manicured lagoons and canals. Burnham called the fair “the third greatest event in American history,” and while such a statement might be the hyperbolic doting of a loving parent, the fair’s impact was indeed deep. It was a premier showcase for American exceptionalism and brought the City Beautiful movement to the lips of every municipal planner in the nation, the trickle-down effect of which is evident in almost every major American city today. While Burnham’s most ambitious design was a 1906 rewo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The City Beautiful and the Birth of the American Monument

- Chapter 2 Uncle Joe and the Long Road to the Lincoln Memorial

- Chapter 3 Competing Designs

- Chapter 4 Bacon and French

- Chapter 5 The Temple Design and Construction

- Chapter 6 The Statue and the Interior Decorations

- Chapter 7 The Dedication

- Chapter 8 Marian Anderson and the Memorial’s New Role

- Chapter 9 1963

- Chapter 10 The Legacy of Protest and Politics

- Chapter 11 Old Abe in the Moonlight

- Lincoln’s Speeches

- Timeline

- Bibliography and Further Reading

- Index