eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

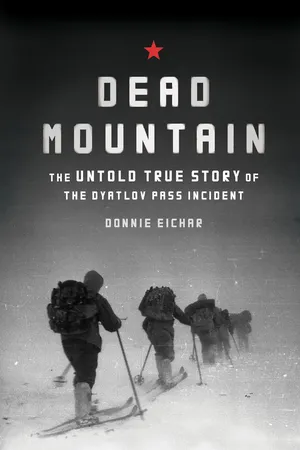

Dead Mountain

The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

About this book

The New York Times and Wall Street Journal Nonfiction Bestseller that explores the gripping Dyatlov Pass incident that took the lives of nine young Russian hikers in 1959.

What happened that night on Dead Mountain?

In February 1959, a group of nine experienced hikers in the Russian Ural Mountains died mysteriously on an elevation known as Dead Mountain. Eerie aspects of the mountain climbing incident—unexplained violent injuries, signs that they cut open and fled the tent without proper clothing or shoes, a strange final photograph taken by one of the hikers, and elevated levels of radiation found on some of their clothes—have led to decades of speculation over the true stories and what really happened.

Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident delves into the untold story through unprecedented access to the hikers' own journals and photographs, rarely seen government records, dozens of interviews, and author Donnie Eichar's retracing of the hikers' fateful journey in the Russian winter.

An instant historical nonfiction bestseller upon its release, this is the dramatic real story of what happened on Dead Mountain.

GRIPPING AND BIZARRE: This is a fascinating portrait of young adventurers in the Soviet era, and a skillful interweaving of the hikers' narrative, the investigators' efforts, and the author's investigations. Library Journal hailed "the drama and poignancy of Eichar's solid depiction of this truly eerie and enduring mystery."

FOR FANS OF UNSOLVED MYSTERIES: Unsolved true crimes and historical mysteries never cease to capture our imaginations. The Dyatlov Pass incident was little known outside of Russia until film producer and director Donnie Eichar brought the decades-old mystery to light in a book that reads like a mystery.

FASCINATING VISUALS: This well-researched volume includes black-and-white photographs from the cameras that belonged to the hikers, which were recovered after their deaths, along with explanatory graphics breaking down some of the theories surrounding the mysterious incident.

Perfect for:

What happened that night on Dead Mountain?

In February 1959, a group of nine experienced hikers in the Russian Ural Mountains died mysteriously on an elevation known as Dead Mountain. Eerie aspects of the mountain climbing incident—unexplained violent injuries, signs that they cut open and fled the tent without proper clothing or shoes, a strange final photograph taken by one of the hikers, and elevated levels of radiation found on some of their clothes—have led to decades of speculation over the true stories and what really happened.

Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident delves into the untold story through unprecedented access to the hikers' own journals and photographs, rarely seen government records, dozens of interviews, and author Donnie Eichar's retracing of the hikers' fateful journey in the Russian winter.

An instant historical nonfiction bestseller upon its release, this is the dramatic real story of what happened on Dead Mountain.

GRIPPING AND BIZARRE: This is a fascinating portrait of young adventurers in the Soviet era, and a skillful interweaving of the hikers' narrative, the investigators' efforts, and the author's investigations. Library Journal hailed "the drama and poignancy of Eichar's solid depiction of this truly eerie and enduring mystery."

FOR FANS OF UNSOLVED MYSTERIES: Unsolved true crimes and historical mysteries never cease to capture our imaginations. The Dyatlov Pass incident was little known outside of Russia until film producer and director Donnie Eichar brought the decades-old mystery to light in a book that reads like a mystery.

FASCINATING VISUALS: This well-researched volume includes black-and-white photographs from the cameras that belonged to the hikers, which were recovered after their deaths, along with explanatory graphics breaking down some of the theories surrounding the mysterious incident.

Perfect for:

- Fans of nonfiction history books and true crime

- Anyone who enjoys real-life mountaineering and survival stories such as Into Thin Air, Buried in the Sky, The Moth and the Mountain, and Icebound: Shipwrecked at the Edge of the World

- Readers seeking Cold War narratives and true stories from the Soviet era

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dead Mountain by Donnie Eichar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

2012

IT IS NEARLY TWENTY BELOW ZERO AS I CRUNCH THROUGH knee-deep snow in the direction of Dyatlov Pass. It’s the middle of winter and I have been trekking with my Russian companions through the northern Ural Mountains for over eight hours and I’m anxious to reach our destination, but it’s becoming increasingly difficult to put one foot in front of the other. Visibility is low, and the horizon is lost in a milky-white veil of sky and ground. Only the occasional dwarf pine, pushing through the snow’s crust, reminds me that there is dormant life beneath my feet. The knee-high boots I am wearing—an “Arctic Pro” model I purchased on the Internet two months ago—are supposed to be shielding my feet from the most glacial temperatures. Yet at the moment the inner toes of my right foot are frozen together, and I am already having dark visions of amputation. I don’t complain, of course. The last time I expressed any hint of dissatisfaction, my guide Vladimir leaned over and said, “This is Siberia.” I later learn this isn’t technically Siberia, only the gateway. The real Siberia, which stretches to the east all the way to the Pacific Ocean, begins on the other side of the Ural Mountains. But then “Siberia,” historically, has been less a geographical designation than a state of mind, a looming threat—the frozen hell on earth to which czarist and Communist Russias sent their political undesirables. By this definition, Siberia is not so much a place as it is a hardship to endure, and perhaps that’s what Vladimir means when he says that we are in Siberia. I trudge on.

I have taken two extended trips to Russia, traveled over 15,000 miles, left my infant son and his mother and drained all of my savings in order to be here. And now we are less than a mile away from our terminus: Holatchahl (sometimes transliterated as “Kholat-Syakhyl”), a name that means “Dead Mountain” in Mansi, the indigenous language of the region. The 1959 tragedy on Holatchahl’s eastern slope has since become so famous that the area is officially referred to as Dyatlov Pass, in honor of the leader of the hiking group that perished there. This last leg of our journey will not be easy: The mountain is extremely remote, the cold punishing and my companions tell me I am the first American to attempt this route in wintertime. At the moment I don’t find this distinction particularly inspiring or comforting. I force my attention away from my frozen toes and to our single objective: Find the location of the tent where nine hikers met their end over half a century ago.

Just over two years ago I would never have imagined myself here. Two years ago I had never heard the name Dyatlov or the incident synonymous with it. I stumbled upon the case quite by accident, while doing research for a scripted film project I was developing in Idaho—one that had nothing to do with hikers or Russia. My interest in the half-century-old mystery started out innocently enough, at a level one might have for a particularly compelling Web site to which one returns compulsively. In fact, I did scour the Internet for every stray detail, quickly exhausting all the obvious online sources, both reliable and sketchy. My attraction to the Dyatlov case turned fanatical and all-consuming, and I became desperate for more information.

The bare facts were these: In the early winter months of 1959, a group of students and recent graduates from the Ural Polytechnic Institute (now Ural State Technical University) departed from the city of Sverdlovsk (as Yekaterinburg was known during the Soviet era) on an expedition to Otorten Mountain in the northern Urals. All members of the group were experienced in lengthy ski tours and mountain expeditions, but, given the time of year, their route was estimated to be of the highest difficulty—a designation of Grade III. Ten days into the trip, on the first of February, the hikers set up camp for the night on the eastern slope of Holatchahl mountain. That evening, an unknown incident sent the hikers fleeing from their tent into the darkness and piercing cold. Nearly three weeks later, after the group failed to return home, government authorities dispatched a search and rescue team. The team discovered the tent, but found no initial sign of the hikers. Their bodies were eventually found roughly a mile away from their campsite, in separate locations, half-dressed in subzero temperatures. Some were found facedown in the snow; others in fetal position; and some in a ravine clutching one another. Nearly all were without their shoes.

After the bodies were transported back to civilization, the forensic analysis proved baffling. While six of the nine had perished of hypothermia, the remaining three had died from brutal injuries, including a skull fracture. According to the case files, one of the victims was missing her tongue. And when the victims’ clothing was tested for contaminants, a radiologist determined certain articles to contain abnormal levels of radiation.

After the close of the investigation, the authorities barred access to Holatchahl mountain and the surrounding area for three years. The lead investigator, Lev Ivanov, wrote in his final report that the hikers had died as a result of “an unknown compelling force,” a euphemism that, despite the best efforts of modern science and technological advances, still defines the case fifty-plus years later.

With no eyewitnesses and over a half century of extensive yet inconclusive investigations, the Dyatlov hiking tragedy continues to elude explanation. Numerous books have been published in Russia on the subject, varying in quality and level of research, and with most of the authors refuting the others’ claims. I was surprised to learn that none of these Russian authors had ever been to the site of the tragedy in the winter. Speculation in these books and elsewhere ranged from the mundane to the crackpot: avalanche, windstorm, murder, radiation exposure, escaped-prisoner attack, death by shock wave or explosion, death by nuclear waste, UFOs, aliens, a vicious bear attack and a freak winter tornado. There is even a theory that the hikers drank a potent moonshine, resulting in their instant blindness. In the last two decades, some authors have suggested that the hikers had witnessed a top-secret missile launch—a periodic occurrence in the Urals at the height of the Cold War—and had been killed for it. Even self-proclaimed skeptics, who attempt to cut through the intrigue in order to posit scientific explanations, are spun into a web of conspiracy theories and disinformation.

One heartbreaking fact, however, remained clear to me: Nine young people died under inexplicable circumstances, and many of their family members have since passed away without ever knowing what happened to their loved ones. Would the remaining survivors go to their graves with the same unanswered questions?

In my work as a documentary filmmaker, my job has been to uncover the facts of a story and piece them together in a compelling fashion for an audience. Whatever external events might draw me to a story, I am interested in people with consuming passions. And in examining the fates of passionate characters, I am often pulled back in time to explore the history behind their personal victories and tragedies. Whether I was stepping into the psyche of the first blind Ironman triathletes in Victory Over Darkness, or untangling the fate of late photojournalist Dan Eldon for my short documentary Dan Eldon Lives Forever, I was ultimately looking to solve a human puzzle.

I had certainly found a puzzle in the Dyatlov incident, but my fascination with the case went beyond a desire to find a solution. The Dyatlov hikers, when not in school, had been exploring loosely charted territory in an age before Internet and GPS. The setting—the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War—could not have been further from that of my own upbringing, but there was a purity to the hikers’ travels that resonated with me.

I grew up in the 1970s and ’80s on the central Gulf Coast of Florida, the land of limitless sunshine. I had been born to teenage parents and there was a free, easygoing quality to my entire childhood. When I wasn’t in school, you could find me fishing or surfing in the warm coastal waters. In the summer of 1987, when I was fifteen, I took a trip with my father to the surfers’ playground of Costa Rica. It was my first trip out of the country, and at a time when tourists were not yet flocking to Central America. The resources available to off-the-grid travelers were limited, and my dad and I had to rely on mail-order maps to direct us to the country’s best surf beaches. When the maps arrived, I’d spread them out on the kitchen table and study the curves of the coastline and the comically specific instructions that hinted at adventure: “Pay off the locals with colones to access this gate” or “look for huge tree near river mouth to find wave.”

As soon as we stepped off the plane in San José, with only our maps and a single Spanish phrase book to guide us, we were weightless, living moment to moment. In the following days, we rode flawless waves on secluded beaches, camped out under tranquil moonlight, survived insect infestations, and shared our space with howler monkeys, crocodiles and boa constrictors. Our far-flung adventures created a sense of camaraderie and shared heroism between my dad and me. Though I would hardly compare tropical Central America with subarctic Russia, memories of that time lent to my appreciation of why these young Soviets had repeatedly risked the dangers of the Ural wilderness in exchange for the fellowship that outdoor travel brings.

There was, of course, the central mystery of the case, with its bewildering set of clues. Why would nine experienced outdoorsmen and -women rush out of their tent, insufficiently clothed, in twenty-five-degrees-below-zero conditions and walk a mile toward certain death? One or two of them might have made the unfathomable mistake of leaving the safety of camp, but all nine? I could find no other case in which the bodies of missing hikers were found, and yet after a criminal investigation and forensic examinations, there was no explanation given for the events leading to their deaths. And while there are cases throughout history of single hikers or mountaineering groups disappearing without a trace, in those instances, the cause of death is quite clear—either they had encountered an avalanche or had fallen into a crevasse. I wondered how, in our globalized world of instant access to an unprecedented amount of data, and our sophisticated means of pooling our efforts, a case like this could remain so stubbornly unsolved.

My investigative synapses really started to fire when I learned that the single surviving member of the Dyatlov group, Yuri Yudin, was still alive. Yudin had been the tenth member of the hiking group, until he decided to turn back early from the expedition. Though he couldn’t have known it at the time, it was a decision that would save his life. It must also, I imagined, have left him with a chronic case of survivor’s guilt. I calculated that Yudin would now be in his early to mid-seventies. And though he rarely talked to the press, I wondered: Could he be persuaded to come out of his seclusion?

Although my initial efforts to find Yudin got me nowhere, I was able to make contact with Yuri Kuntsevich, the head of the Dyatlov Foundation in Yekaterinburg, Russia. Kuntsevich explained that the foundation’s mission was both to preserve the memories of the hikers and to uncover the truth of the 1959 tragedy. According to Kuntsevich, not all the files from the Dyatlov case had been made public, and the foundation was hoping to persuade Russian officials to reopen the criminal investigation. Speaking through a translator, he was perfectly cordial and offered that he might have information to help my understanding of the incident. However, my specific queries about the case—including how to reach Yuri Yudin—resulted in only vague or cryptic responses. At last he put the onus on me: “If you seek the truth in this case, you must come to Russia.”

Kuntsevich had no real idea who I was—I had introduced myself as a filmmaker and we’d spoken for forty-five minutes—yet he had extended an unambiguous invitation. Or was it a summons? I was not Russian. I didn’t speak the language. I had seen snow less than a dozen times in my life. Who was I to go roaming through Russia in the middle of winter to unravel one of the country’s most baffling mysteries?

As I approached Dyatlov Pass more than two years later, pausing every so often to blow warm air into my gloves, I found myself asking the same question: Why am I here?

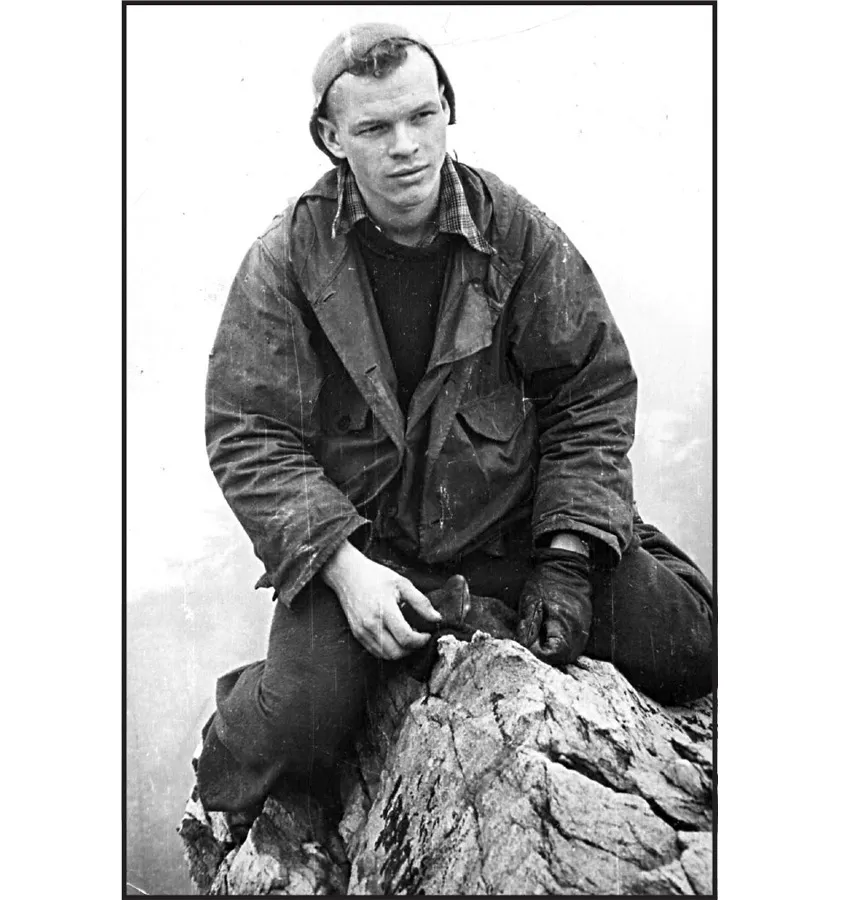

Igor Dyatlov, ca. 1957–1958

2

JANUARY 23, 1959

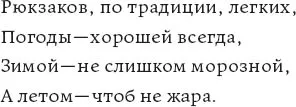

Let your backpacks be light,

weather always fine,

winter not too cold,

and summer without heat.

weather always fine,

winter not too cold,

and summer without heat.

—Georgy Krivonishchenko, excerpt from New Year’s poem, 1959

IF ONE HAD BEEN ABLE TO GLIMPSE INSIDE DORMITORY 531 on January 23, 1959, one would have seen the very picture of fellowship, youth, and happiness. The room itself was nothing to look at. Like most dorms at Sverdlovsk’s Ural Polytechnic Institute, the furnishings were serviceable at best; and, for half the year, the building rumbled under the toil of a coal-stoked boiler. One might have assumed in observing the room—with its blistered wallpaper, lumpy mattresses and lingering odors from the communal kitchen—that the students residing here must take pleasure in things outside material comforts. They must certainly live for books, art, friends and nature, interests that could carry them beyond this dingy cupboard. And one would be right. On that fourth Friday in January, a month before the school term was to begin, nine friends in their early twenties were engaged in last-minute preparations for a trip that would take them far beyond the confines of dormitory life.

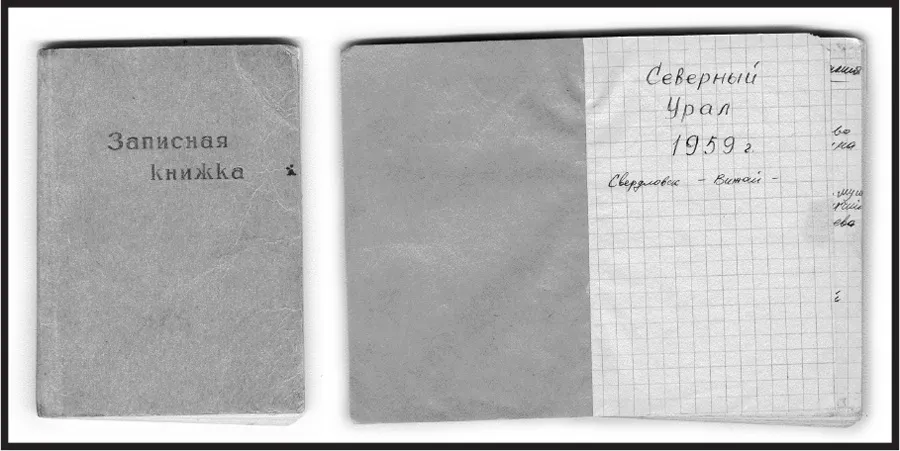

The front cover and first page of the Dyatlov group’s diary.

The room that evening was charged with excitement, each member of the group busy with a designated task and each talking over the others in an eagerness to be heard. Their group diary captured snatches of their conversation:

We’ve forgotten salt!

Igor! Where are you?

Where’s Doroshenko, why doesn’t he take 20 packages?

Will we play mandolin on the train?

Where are the scales?

Damn, it does not fit in!

Who has the knife?

Igor! Where are you?

Where’s Doroshenko, why doesn’t he take 20 packages?

Will we play mandolin on the train?

Where are the scales?

Damn, it does not fit in!

Who has the knife?

One of the young men stuffed ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Contents

- Map

- Author’s Note

- Prologue: February 1959

- 1 2012

- 2 January 23, 1959

- 3 February 1959

- 4 2010

- 5 January 24, 1959

- 6 February 1959

- 7 2012

- 8 2012

- 9 January 25, 1959

- 10 February 1959

- 11 2012

- 12 January 25–26, 1959

- 13 February 1959

- 14 2012

- 15 January 26–28, 1959

- 16 February–March 1959

- 17 2012

- 18 January 28–February 1, 1959

- 19 March 1959

- 20 2012

- 21 March 1959

- 22 2012

- 23 March–May 1959

- 24 2012

- 25 May 1959

- 26 2013

- 27 2013

- 28 February 1–2, 1959

- Cast of Characters

- The Hikers’ Timeline

- The Investigation Timeline

- Acknowledgments

- Index

- About the Author