- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

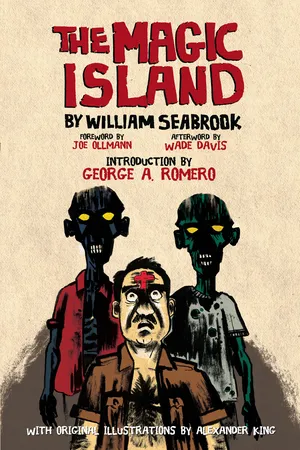

The Magic Island

About this book

"The best and most thrilling book of exploration that we have ever read … [an] immensely important book." — New York Evening Post

"A series of excellent stories about one of the most interesting corners of the American world, told by a keen and sensitive person who knows how to write." — American Journal of Sociology

"It can be said of many travelers that they have traveled widely. Of Mr. Seabrook a much finer thing may be said — he has traveled deeply." — The New York Times Book Review

This fascinating book, first published in 1929, offers firsthand accounts of Haitian voodoo and witchcraft rituals. Journalist and adventurer William Seabrook introduced the concept of the walking dead ― zombies ― to the West with his illustrated travelogue. He relates his experiences with the voodoo priestess who initiated him into the religion's rituals, from soul transference to resurrection. In addition to twenty evocative line drawings by Alexander King, this edition features a new Foreword by cartoonist and graphic novelist Joe Ollmann, a new Introduction by George A. Romero, legendary director of Night of the Living Dead, and a new Afterword by Wade Davis, Explorer in Residence at the National Geographic Society.

"A series of excellent stories about one of the most interesting corners of the American world, told by a keen and sensitive person who knows how to write." — American Journal of Sociology

"It can be said of many travelers that they have traveled widely. Of Mr. Seabrook a much finer thing may be said — he has traveled deeply." — The New York Times Book Review

This fascinating book, first published in 1929, offers firsthand accounts of Haitian voodoo and witchcraft rituals. Journalist and adventurer William Seabrook introduced the concept of the walking dead ― zombies ― to the West with his illustrated travelogue. He relates his experiences with the voodoo priestess who initiated him into the religion's rituals, from soul transference to resurrection. In addition to twenty evocative line drawings by Alexander King, this edition features a new Foreword by cartoonist and graphic novelist Joe Ollmann, a new Introduction by George A. Romero, legendary director of Night of the Living Dead, and a new Afterword by Wade Davis, Explorer in Residence at the National Geographic Society.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One:

THE VOODOO RITES

Chapter I

SECRET FIRES

LOUIS, son of Catherine Ozias of Orblanche, paternity unknown—and thus without a surname was he inscribed in the Haitian civil register—reminded me always of that proverb out of hell in which Blake said, “He whose face gives no light shall never become a star.”

It was not because Louis’ black face, frequently perspiring, shone like patent leather; it glowed also with a mystic light that was not always heavenly.

For Louis belonged to the chimeric company of saints, monsters, poets, and divine idiots. He used to get besotted drunk in a corner, and then would hold long converse with seraphim and demons, also from time to time with his dead grandmother who had been a sorceress.

In addition to these qualities, Louis was our devoted yard boy. He served us, in the intervals of his sobriety, with a passionate and all-consuming zeal.

We had not chosen Louis for our yard boy. He had chosen us. He had also chosen the house we lived in. These two things had happened while we were still at the Hotel Montagne. And they had seemed to us slightly miraculous, though the grapevine telegraph of servants in Port-au-Prince might adequately have explained both. Katie and I had been house-hunting. We had been shown unlivably ostentatious plaster palaces with magnificent gardens, and livable wooden villas with inadequate gardens or no gardens at all, until we had begun to despair. One afternoon as we left the hotel gate, strolling down the hill to Ash Pay Davis’s, a black boy, barefooted and so ragged that we thought he was a beggar, stopped us and said in creole with affectionate assurance, as if he had known us all our lives, “I have found the house for you.” Not a house, mind you. Nor was there any emphasis on the the; there couldn’t be in creole. He said literally, “M’ té joiend’ caille ou” (I have found your house).1

What we did may sound absurd. We returned to the hotel, got out our car, took Louis inside—he had wanted to ride the running-board—and submitted to his guidance. He directed us into the fashionable Rue Turgeau toward the American club and colony, but before reaching that exclusive quarter, we turned unfamiliarly left and then up a lane that ran into the jungle valley toward Pétionville, and there where city and jungle joined was a dilapidated but beautiful garden of several acres and in its midst a low, rambling, faded pink one-story house with enormous verandas on a level with the ground.

Some of the doors were locked; the rest were nailed up. Behind the house were stone-built servants’ quarters and a kitchen, also locked. There was a bassin (swimming-pool) choked with débris and leaves.

Who owned this little dilapidated paradise, whether it was for rent, how much the rent might be—these were matters outside the scope of Louis’ genius. He had not inquired before coming to find us, and he made no offers or suggestions now.

We thanked Louis, dropped him at Sacré Cœur, told him to come see us at the hotel next morning, then drove to Ash Pay’s and discovered after considerable telephoning that the place belonged to Maître Morel and might be rented for thirty dollars a month. Toussaint, black interpreter for the brigade who dabbled helpfully in everything, would get us the keys on Wednesday afternoon when Maître Morel returned from Saint Marc.

Louis did not come to the hotel next morning, nor the morning after, but when we went with Toussaint three days later to open the house, we were received blandly by Louis, who was already at home in a corner of the brick-paved veranda to which he had in the interval transported all his earthly possessions, consisting of a pallet, an old blanket, an iron cooking-pot, a candle-stub, and a small wooden box containing doubtless his more intimate treasures. In the pot were the remains of some boiled plantain, apparently his sole sustenance.

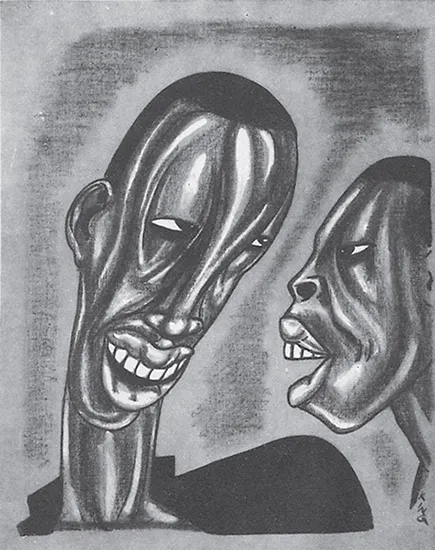

“Louis’ face glowed with a light that was not always heavenly.”

Neither he nor we ever mentioned the matter of employing him. Several days were going to elapse before we could move in, but I gave him the keys to the house then and there. I also gave him ten gourdes, the equivalent of two dollars, which was a large sum of money, and told him to buy for himself what was needful, suggesting a new shirt and a supply of food. He was undernourished, and with that new wealth he could feast for a week; the price of a chicken in Haiti is twenty cents.

Returning some days later, I found him with a new pair of tennis shoes, a magnificently gaudy new scarf knotted round his neck, lying on his back in the grass beneath the shade of a mango tree, blissfully and inoffensively drunk, singing a little happy tune which he made as it went, inviting the birds to come and admire his new clothes. His shirt was as before. His whole shoulder protruded from a rent in it. I examined the cook-pot. It contained the remains of some boiled plantain, and it had apparently contained nothing else in the interval. I have told you, I think, that Louis was a saint. Even so, I fear it is going to be difficult to make you understand Louis, unless you have read sympathetically the lives of the less reputable saints and have also lived in a tropical country like Haiti.

Of course when we furnished the house and moved in, we had additional servants—the dull, competent butler, a middle-aged woman cook, and for blanchisseuse a plump little wench with flashing teeth and roving eyes who promptly fell in love with Louis, gave him money, and more intimate favors when he permitted it. Having four servants was not ostentatious in Port-au-Prince, even for us who in New York habitually have none. It was the general custom. We paid the four of them a grand sum total of thirty-one dollars monthly, and they found their own food. The last three were reasonably efficient, as servants, doing generally what they were told; but Louis, who never did what he was told, was nevertheless in actual fact, putting quite aside his fantastic power of holding our affection, the most efficient servant of them all. The things he wanted to do, he did without being ordered, and they were many. For instance, there was the matter of our small sedan. He knew nothing about its mechanical insides and could never learn to change a tire, but he took a passionate pride in keeping it clean and polished. He groomed it as if it were alive. When it came home covered with caked mud he dropped no matter what and labored like a madman. He would never clean up the garden, burn brush, carry stones, but during the first week he anticipated our intentions by appearing with vines and flowers for transplanting, the earth still clinging to their roots, which he had got from God knows where. And these also he attended devotedly as if they were alive in a more than vegetable sense.

He delighted in doing personal things to please us. Sometimes when we thought we needed him he was as tranquilly drunk as an opium-smoking Chinaman or off chasing the moon, but at moments when we least expected anything he would appear with a great armful of roses for Katie or a basket for me of some queer fruit not seen in the markets. On rare occasions, sometimes when drinking, sometimes not, he was hysterically unhappy and could not be comforted. But usually he was the soul of joy. And in the household Louis gradually centered his allegiance and chief concern on me. I mention this because most people, whether servants, kinsfolk, intimate friends, or casual acquaintances, find Katie the more admirable human being of us two. But Louis put me first. He began gradually to give me confidences. He felt, as time passed, that I understood him.

And what has all this to do with the dark mysteries of Voodoo? you may ask, but I suspect that you already know. It was humble Louis and none other who set my feet in the path which led finally through river, desert, and jungle, across hideous ravines and gorges, over the mountains and beyond the clouds, and at last to the Voodoo Holy of Holies. These are not metaphors. The topography of Haiti is a tropical-upheaved, tumbled-towering madland of paradises and infernos. There are sweet plains of green-waving sugar cane, coral strands palm-fronded, impenetrable jungles of monstrous tangled growth, arid deserts where obscene cactus rises spiked and hairy to thrice the height of a tall man on horseback and where salamanders play; there are black canyons which drop sheer four thousand feet, and forbidding mornes which rise to beyond nine thousand. But the trail which led among them and ended one night when I knelt at last before the great Rada drums, my own forehead marked with blood—that trail began at my own back doorstep and led only across the garden to my yard boy Louis’ bare, humble quarters where a tiny light was burning.

In a cocoanut shell filled with oil the little wick floated, its clear-flamed tip smaller than a candle’s, and before it, raised on a pile of stones such as a child might have built in play, was a stuffed bag made of scarlet cloth, shaped like a little water-jug, tied round with ribbon, surmounted by black feathers. Louis had come on tiptoe shortly after midnight, seeing me reading late and Katie gone to a dance at the club, whose music floated faintly across from Turgeau in the stillness. He explained that a mystère, a loi, which is a god or spirit, had entered the body of a girl who lived in a hut up the ravine behind our house, and that everywhere throughout our neighborhood, in the many straw-thatched huts of the ravine, likewise in the detached servant quarters of the plaster palaces of American majors and colonels, hundreds of similar little sacred flames were burning.

Thus, and as time passed, confidence engendering confidence, I learned from Louis that we white strangers in this twentieth-century city, with our electric lights and motor cars, bridge games and cocktail parties, were surrounded by another world invisible, a world of marvels, miracles, and wonders—a world in which the dead rose from their graves and walked, in which a man lay dying within shouting distance of my own house and from no mortal illness but because an old woman out in Léogane sat slowly unwinding the thread wrapped round a wooden doll made in his image; a world in which trees and beasts talked for those whose ears were attuned, in which gods spoke from burning bushes, as on Sinai, and sometimes still walked bodily incarnate as in Eden’s garden.

I also learned from Louis, or at least began to glimpse through him, something which I think has never been fully understood: that Voodoo in Haiti is a profound and vitally alive religion—alive as Christianity was in its beginnings and in the early Middle Ages when miracles and mystical illuminations were common everyday occurrences—that Voodoo is primarily and basically a form of worship, and that its magic, its sorcery, its witchcraft (I am speaking technically now), is only a secondary, collateral, sometimes sinisterly twisted by-product of Voodoo as a faith, precisely as the same thing was true in Catholic mediaeval Europe.

In short, I learned from Louis that while the High Commissioner, his lady, and the colonel had called and taken tea in our parlor, the high gods had been entering by the back door and abiding in our servants’ lodge.

Nor was this surprising. It has been a habit of all gods from immemorial days. They have shown themselves singularly indifferent to poli...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Foreword to the 1929 Edition

- Part One: The Voodoo Rites

- Part Two: Black Sorcery

- Part Three: The Tragic Comedy

- Part Four: Trails Winding

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Magic Island by William Seabrook,Alexander King, Alexander King, Joe Ollmann in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Religious Fundamentalism & Cults. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.