Chapter 1:

Time in Print

What does history look like? How do you draw time?

While historical texts have long been subject to critical analysis, the formal and historical problems posed by graphic representations of time have largely been ignored. This is no small matter: graphic representation is among our most important tools for organizing information.1 Yet, little has been written about historical charts and diagrams. And, for all of the excellent work that has been recently published on the history and theory of cartography, we have few examples of critical work in the area of what Eviatar Zerubavel has called time maps.2 This book is an attempt to address that gap.

In many ways, this work is a reflection on lines—straight and curved, branching and crossing, simple and embellished, technical and artistic—the basic components of historical diagrams. Our claim is that the line is a much more complex and colorful figure than is usually thought. Historians will probably appreciate this aspect of the book fairly easily. We all use simple line diagrams in our classrooms—what we usually call “timelines”—to great effect. We get them, our students get them, they translate wonderfully from weighty analytic history books to thrilling narrative ones.

But simple and intuitive as they seem, these timelines are not without a history themselves. They were not always here to help us in our lectures, and they have not always taken the forms that we unthinkingly give them. They are such a familiar part of our mental furniture that it is sometimes hard to remember that we ever acquired them in the first place. But we did. And the story of how is worth telling, because it helps us understand where our contemporary conceptions of history come from, how they work, and, especially, how they rely on visual forms. It is also worth telling because it’s a good story, full of twists and turns and unexpected characters, soon to be revealed.

Another reason for the gap in our historical and theoretical understanding of timelines is the relatively low status that we generally grant to chronology as a kind of study. Though we use chronologies all the time, and could not do without them, we typically see them as only distillations of complex historical narratives and ideas. Chronologies work, and—as far as most people are concerned—that’s enough. But, as we will show in this book, it wasn’t always so: from the classical period to the Renaissance in Europe, chronology was among the most revered of scholarly pursuits. Indeed, in some respects, it held a status higher than the study of history itself. While history dealt in stories, chronology dealt in facts. Moreover, the facts of chronology had significant implications outside of the academic study of history. For Christians, getting chronology right was the key to many practical matters such as knowing when to celebrate Easter and weighty ones such as knowing when the Apocalypse was nigh.

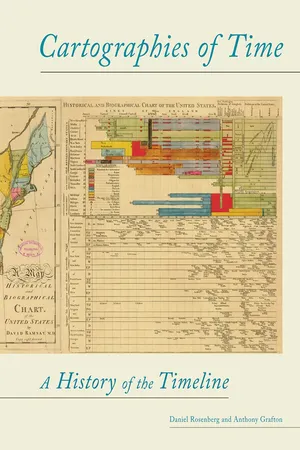

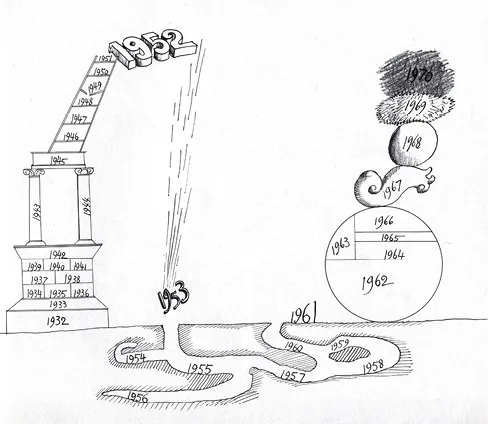

[1]

1932–1970 “calendar,” Saul Steinberg, Untitled, 1970

__________

Ink, collage, and colored pencil on paper, 14 ½ x 23 inches, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University © The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Yet, as historian Hayden White has argued, despite the clear cultural importance of chronology, it has been difficult to induce Western historians to think of it as anything more than a rudimentary form of historiography. The traditional account of the birth of modern historical thinking traces a path from the enumerated (but not yet narrated) medieval date lists called annals, through the narrated (but not yet narrative) accounts called chronicles, to fully narrative forms of historiography that emerge with modernity itself.3 According to this account, for something to qualify as historiography, it is not enough that it “deal in real, rather than merely imaginary, events; and it is not enough that [it represent] events in its order of discourse according to the chronological framework in which they originally occurred. The events must be...revealed as possessing a structure, an order of meaning, that they do not possess as mere sequence.”4 Long thought of as “mere sequences,” in our histories of history, chronologies have usually been left out.

But, as White argues, there is nothing “mere” in the problem of assembling coherent chronologies nor their visual analogues. Like their modern successors, traditional chronographic forms performed both rote historical work and heavy conceptual lifting. They assembled, selected, and organized diverse bits of historical information in the form of dated lists. And the chronologies of a given period may tell us as much about its visions of past and future as do its historical narratives.

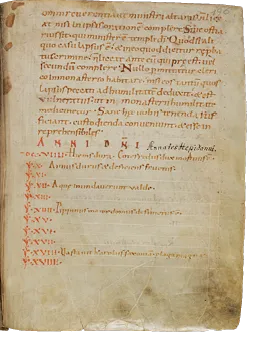

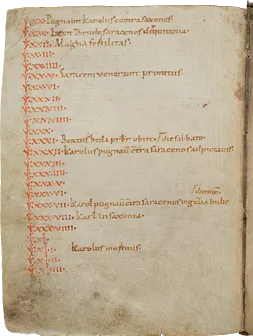

White gives the example of the famous medieval manuscript chronology called the Annals of St. Gall, which records events in the Frankish kingdoms during the eighth, ninth, and tenth centuries in chronological order with dates in a left hand column and events on the right. [figs. 2–3] To a modern eye, annals such as these appear strange and antic, beginning and ending seemingly without reason, mashing up categories helter-skelter like the famous Chinese encyclopedia conjured by Jorge Luis Borges. Here, for example, is a section covering the years 709 to 734.

709. Hard winter. Duke Gottfried died.

710. Hard year and deficient in crops.

711.

712. Flood everywhere.

713.

714. Pippin, mayor of the palace died.

715.

716.

717.

718. Charles devastated the Saxon with great destruction.

719.

720. Charles fought against the Saxons.

721. Theudo drove the Saracens out of Aquitaine.

722. Great crops.

723.

724.

725. Saracens came for the first time.

730.

731. Blessed Bede, the presbyter, died.

732. Charles fought against the Saracens at Poitiers on Saturday.

733.

734.5

[2–3]

Annals of St. Gall, Monastery of St. Gall, Switzerland, mid-eleventh century

From a historiographical point of view, the text seems to be missing a great deal. Though it meets a very minimal definition of narrative (it is referential, it represents temporality), it possesses few or none of the characteristics that we normally expect in a story, much less a history. The Annals make no distinction between natural occurrences and human acts; they give no indication of cause and effect; no entry is given more priority than another. Below the level of years, references to time are strangely gnomic: in the year 732, for example, the text indicates that Charles Martel “fought the Saracens on Saturday,” but it does not specify which Saturday. Above the level of the year, there is no distinction among periods, and lists begin and end as nameless chroniclers pick up and put down their pens. But this should not be taken to suggest that the St. Gall manuscripts are without meaningful structure. To the contrary, White argues, in their very form, these annals breathe with the life of the Middle Ages. The Annals of St. Gall, White argues, vividly figure a world of scarcity and violence, a world in which “forces of disorder” occupy the forefront of attention, “in which things happen to people rather than one in which people do things.”6 As such, they represent a form closely calibrated to both the interests and the vision of their users.

Parallel observations have been made by scholars of non-Western historiography such as the great Indian historian Romila Thapar. Thapar has long emphasized that genealogy and chronicle are not primitive efforts to write what would become history in other hands, but powerful, graphically dense ways of describing and interpreting the past.7 And in recent years, historians of premodern Europe like Roberto Bizzocchi, Christiane Klapisch-Zuber, and Rosamond McKitterick have begun to pay due attention to the graphically sophisticated ways in which genealogical forms—especially the tree—have developed and been used in the historiography of both the premodern and the modern West.8

Addressing the problem of chronology, and especially the problem of visual chronology, means going back to the line, to understand its ubiquity, flexibility, and force. In representations of time, lines appear virtually everywhere, in texts and images and devices. Sometimes, as in the timelines found in history textbooks, the presence of the line couldn’t be more obvious. But in other instances, it is more subtle. On an analog clock, for example, the hour and minute hands trace lines through space; though these lines are circular, they are lines nonetheless. As the linguist George Lakoff and the philosopher Mark Johnson have argued, the linear metaphor is even at work in the digital clock, though no line is actually visible. In this device, the line is present as an “intermediate metaphor”: to understand the meaning of the numbers, the viewer translates them into imagined points on a line.9

Our idea of time is so wrapped up with the metaphor of the line that taking them apart seems virtually impossible. According to the literary critic W. J. T. Mitchell, “The fact is that spatial form is the perceptual basis of our notion of time, that we literally cannot ‘tell time’ without the mediation of space.”10 Mitchell argues that all temporal language is “contaminated” by spatial figures. “We speak of ‘long’ and ‘short’ times, of ‘intervals’ (literally, ‘spaces between’), of ‘before’ and ‘after’—all implicit metaphors which depend upon a mental picture of time as a linear continuum....Continuity and sequentiality are spatial images based in the schema of the unbroken line or surface; the experience of simultaneity or discontinuity is simply based in different kinds of spatial images from those involved in continuous, sequential experiences of time.”11 And it may well be that Mitchell is right. But recognizing this can only be a beginning. In the field of temporal representation, the line can be everywhere because it is so flexible and its configurations so diverse.

The histories of literature and art furnish an abundant store of examples of the complex interdependence of temporal concepts and figures. And—as in the case of the digital clock—in many instances metaphors that appear to draw their force from a different source in fact contain an implicit linear figure. This is the case even in the famous passage from Shakespeare where Macbeth compares time to an experience of language f...