![]()

PART I

DRAWING FROM LIFE

THE FUNDAMENTALS

In the spring of 1975, I met with John Hejduk, the late dean of the Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture of The Cooper Union, to discuss the possibility of my teaching a section of a class designated Freehand Drawing. A course by that title already in the curriculum was in need of reshaping. Hejduk wished to envigorate the design curriculum with a more liberating drawing program. “I want someone who can teach the figure,” he declared to his close collaborator and colleague, the painter Robert Slutzky. Familiar with my studio work and my teaching in the School of Art, Slutzky arranged the appointment. The dialogue with Hejduk, begun in that meeting, continued for the next quarter century. Those conversations altered and enlarged the drawing curriculum. They illuminated and expanded my understanding of both drawing and teaching over the next three decades.

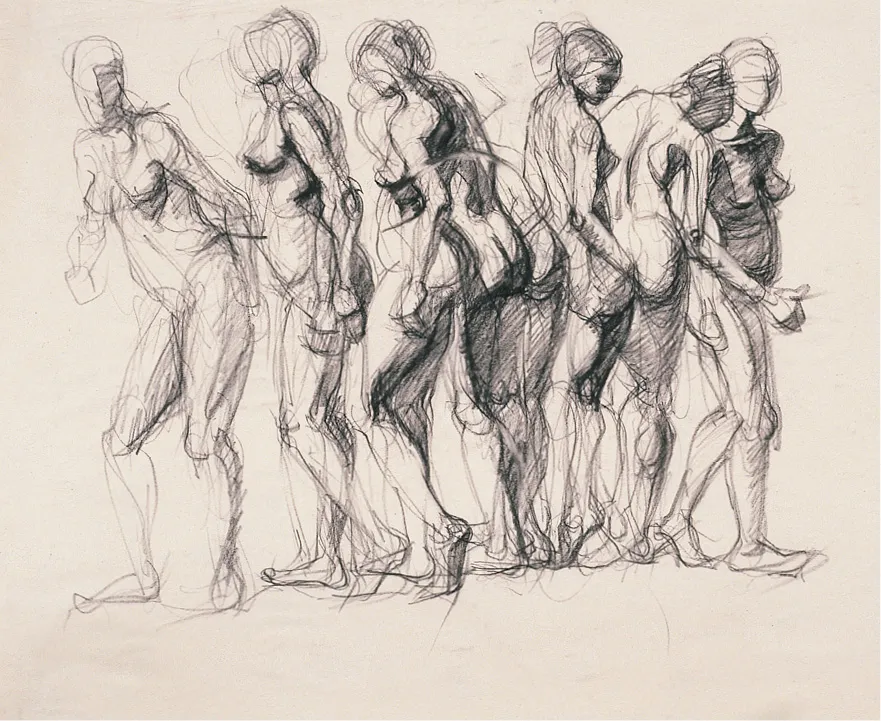

One might ask, why teach architects to draw from the figure at all? Wouldn’t the logical program consist of plan, section, elevation, and perhaps perspective and axonometric drawing? Why not devise a course simply and expansively titled Drawing that would encompass all of the above and also embrace computer-generated drawing? What might an architecture student gain from a year-long intensive drill in drawing from observation—in drawing from life? The answer emanates from the body itself. So much of what the human creature has come to know has been learned from the body—from how it walks, rests, runs, and dances. Invert the phrase “Body of Knowledge” and it becomes “Knowledge of (the) Body.”

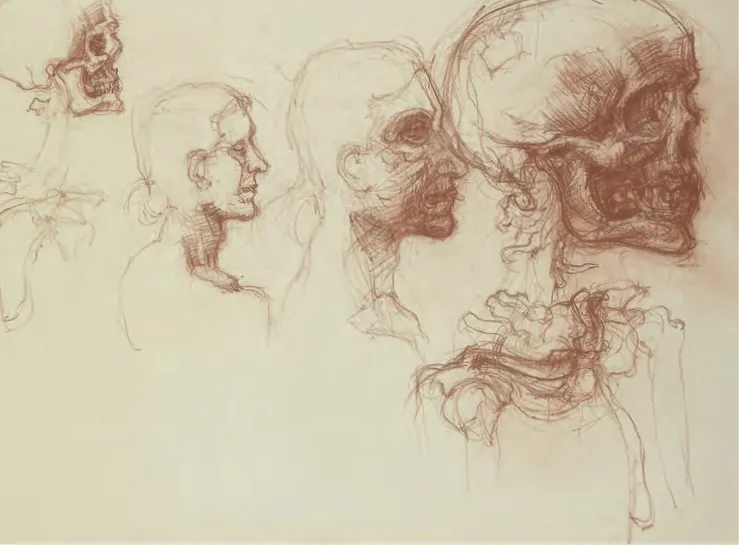

The very concept of measurement begins with the parts and proportions of human anatomy—a foot, an arm’s length, the distance of so many heads or hands. The notion of counting in tens derives from our fingers, our toes. The anatomical word for finger—digit—is also the term for each of the ten units in Arabic enumeration. The cubit, the length from the elbow to the end tip of the middle finger, is famously utilized in Genesis 6:15: God instructs Noah to construct his ark of gopher wood, three hundred cubits in length, fifty cubits in breadth, thirty cubits in height—the first known set of architectural specifications.

From the human skeleton stems primary notions of structure, of shelter and containment: the spine can be taken as a metaphor for uprightness; the rib cage embraces and protects our breath and heartbeat; the pelvis is a bowl for bowels, organs, and fetuses; and the skull frames our vision and houses our very thoughts and imaginings. Our joints not only permit the complexity of our locomotion but anticipate the coming of the hinge and all the myriad inventions of joinery and architectural articulation.

But perhaps the most compelling reason to teach drawing from the figure is the liberating joy of it. It is where all drawing begins. A child makes marks, blotches, scribbles, then hard- or soft-edged geometric shapes, stacks them one on another and names them: mother, father, house, me. It is the self revealed on paper—a declaration and a need.

Drawing entails another form of measurement. From the vast panorama of what the eye perceives, one needs to isolate, translate, and transcribe an image and proportion it to fit the two-dimensional confines of a finite sheet of paper. What width of mark is best to describe a six-foot body on a 36"-high tablet? What drawing medium best suits that scale; what kind of mark suits a 6" x 9" sketchbook? As the figure is scaled to the measure of the page, other questions of space—and the making and marking of space—begin to assert themselves. This is what Hejduk profoundly understood when he commissioned me (in tandem with Slutzky for the first two years) to redefine the first-year Freehand Drawing program.

![]()

WHERE IT ALL BEGINS: PEAS IN A POD

Early on, I tell my students that I promise not to teach them anything “useful.” This, of course, grabs their attention; it is not what they expect. In architecture curricula drawing typically is viewed as utilitarian, a course adjunct to the design studio. In most schools drawing simply involves drafting techniques, nothing more. Only rarely is drawing regarded as expanding architectonic thought, as part of the thought process itself. Texts that link architecture and drawing together are generally how-to books. They deal with plan, section, elevation—or they set forth specific modes of illustration, such as perspective—but they do not address the experience of space or depth.

In my approach to setting up foundational problems, I find it important to teach concept, technique, and skill but imperative to recognize and value divergence. I teach Freehand Drawing to empower rather than “instruct.” Permeating through all the assignments and infusing all of the studio sessions is the concept of that metaphoric dimension—space. There is the obvious concept of space on the paper: it is blank or drawn upon. But how is one able to translate from the three-dimensional to the two-dimensional plane such factors as volume, transparency, and their interpenetration? The ability to master this is the underlying subtext of the course.

My first day of drawing class was a terrifying experience. Only seventeen, I had never contemplated an approach to drawing—much less thought about hanging any of my drawings on the wall and talking about them. Then there was Gussow, with this seemingly intimidating presence and a wide-brimmed hat to match. She was intensely serious about drawing. When it came to the first exercise, I practically carved the pea pod through the entire pad of newsprint. The drawing was miniscule, in the middle of an enormous sheet of paper. But even by the second attempt to draw from an actual pea pod, I was already beginning to study what I was seeing much more carefully. That study, or searching of sight, grew over the course of the year and still lives with me twenty years later. — STEVEN HILLYER

The very first meeting of the Freehand Drawing class provides the opportunity to establish the philosophy of the course. Drawing always begins on that very day. For the first several years, I handled that day in various ways, but in 1979 I happened upon a paragraph in the “Talk of the Town” column in theNew Yorker:

I was shelling peas from my garden the other afternoon, and the ancient figure (attributed to Rabelais) dropped into my mind: “As like as two peas in a pod.” I let it drop on through. I would be disappointed if I found only two peas in a pod, and I would be surprised if they looked exactly alike. Some peas are square, some are hexagonal, some are cone-shaped, some are disc-like, some are even round, and in almost every pod there is one pea, squeezed into the middle or off at one end, that is one-tenth the size of the others. Nature—in my experience with apples and green beans and tomatoes and squash and carrots and red roses and robins and oak trees—is given to variety more than to duplication. One has only to observe, to open the mind as well as the eye, to pierce the generalization. Peas look alike as Chinese look to Westerners or Westerners to Chinese.1

On that very first day, the students are the proverbial peas in a pod. Their names appear on a printout—as yet unattached to faces. Although differentiated by gender, clothing, and other surface attributes, they all appear wonderfully—and similarly—young.

EXERCISES

Draw a pea pod from memory and in such a way that it reveals the peas it contains. Any dr...