eBook - ePub

Symphonies and Other Orchestral Works

Selections from Essays in Musical Analysis

- 576 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Symphonies and Other Orchestral Works

Selections from Essays in Musical Analysis

About this book

More than 100 selections from the noted musicologist's Essays in Musical Analysis cover most of the standard works in the symphonic repertory. Subjects include Beethoven's overtures and symphonies, including the author's famous study of the Ninth Symphony; all Brahms's overtures and symphonies; 11 symphonies by Haydn; six by Mozart; three symphonies each by Schubert, Schumann, and Sibelius; four symphonies by Dvoràk; and many other works by composers from Bach to Vaughan Williams.

Donald Francis Tovey's Essays in Musical Analysis ranks among the English language's most acclaimed works of musical criticism. Praised for their acuteness, common sense, clarity, and wit, they offer entertaining and instructive reading for anyone interested in the classical music repertoire.

Donald Francis Tovey's Essays in Musical Analysis ranks among the English language's most acclaimed works of musical criticism. Praised for their acuteness, common sense, clarity, and wit, they offer entertaining and instructive reading for anyone interested in the classical music repertoire.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Symphonies and Other Orchestral Works by Donald Francis Tovey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Classical Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

BEETHOVEN

FIRST SYMPHONY IN C MAJOR, OP. 21

1 Adagio molto, leading to 2 Allegro con brio, 3 Andante cantabile con moto 4 MENUETTO: Allegro molto, e vivace. 5 Adagio, leading to 6 Allegro molto e vivace.

Beethoven’s first symphony, produced in 1800, is a fitting farewell to the eighteenth century. It has more of the true nineteenth-century Beethoven in its depths than he allows to appear upon the surface. Its style is that of the Comedy of Manners, as translated by Mozart into the music of his operas and of his most light-hearted works of symphonic and chamber music. The fact that it is comedy from beginning to end is prophetic of changes in music no less profound than those which the French Revolution brought about in the social organism. But Beethoven was the most conservative of revolutionists ; a Revolutionist without the R ; and in his first symphony he shows, as has often been remarked, a characteristic caution in handling sonata form for the first time with a full orchestra. But the caution which seems so obvious to us was not noticed by his contemporary critics. We may leave out of account the oft-quoted fact that several Viennese musicians objected to his beginning his introduction with chords foreign to the key; such objectors were pedants miserably behind the culture not only of their own time but of the previous generation. They were the kind of pedants who are not even classicists, and whose grammatical knowledge is based upon no known language. Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, who, much more than his father, was at that time regarded as a founder of modern music by persons who considered the lately deceased Mozart a dangerous person, had gone very much farther in this matter of opening in a foreign key than Beethoven ever went in the whole course of his career. Where the contemporary critics showed intelligent observation was in marking, though with mild censure, the fact that Beethoven’s first symphony is written so heavily for the wind band that it seems almost more like a ‘Harmoniemusik’ than a proper orchestral piece. This observation was technically correct. Beethoven had at that time a young composer’s interest in wind instruments, which he handled with a mastery stimulated by the wind-band (‘Harmonie’) masterpieces of Mozart. His handling of the strings was not less masterly, though his interest in their possibilities developed mightily in later works.

The position then is this : that in his first symphony Beethoven overwhelmed his listeners with a scoring for the full wind band almost as highly developed as it was ever destined to be (except that he did not as yet appreciate the possibilities of the clarinet as an instrument for the foreground). The scale of the work as a whole gave no scope for an equivalent development of the strings. Even to-day there is an appreciable difficulty in accommodating the wind band of Beethoven’s first symphony to a small body of strings, and consequently an agreeable absence of the difficulties of balance which have become notorious in the performance of classical symphonies by large orchestras without double wind.

The introduction, made famous by pedantic contemporary objections to its mixed tonality, has in later times been sharply criticized by so great a Beethoven worshipper as Sir George Grove for its ineffectual scoring. With all respect to that pioneer of English musical culture, such a criticism is evidently traceable to the effect of pianoforte arrangements, which often suggest that a chord which is loud for the individual players of the orchestra is meant to be as loud as a full orchestral passage. When two pianists play these forte-piano chords in a duet, they naturally make as much noise as they can get out of their instrument. This sets up an impression in early life which many conductors and critics fail to get rid of. Hence the complaint that the pizzicato chords of the strings are feeble, a complaint that assumes that it is their business to be forcible.

I am delighted to find myself anticipated by Mr. Vaclav Talich in the view that the opening is mysterious and groping, and that the first grand note of triumph is sounded when the dominant is reached.

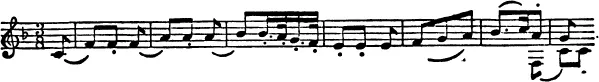

Ex. 1.

For the rest, a list of the principal themes will cover the ground of the work, leaving but little need for comment.

The first theme of the allegro con brio is a quietly energetic, business-like proposition, moving in sequences from tonic to super-tonic, and thence rising through subdominant to dominant.

Ex. 2.

It is the opening of a formal rather than of a big work. If you wish to see the same proposition in a loftier style, look at Beethoven’s C major String Quintet, where the same harmonic plan is executed in a single eight-bar phrase.

The transition-theme needs no quotation. Not only is it extremely formal, but, instead of establishing the key of the ‘second subject’ (G major) by getting on to its dominant, it is contented with the old practical joke, which Mozart uses only in his earlier or lighter works, the joke of taking the mere dominant chord (here the chord of G) as equivalent to the dominant key, and starting in that key with no more ado.

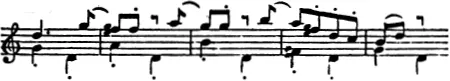

Ex. 3.

It is solemn impertinence to suppose that there is anything early or primitive in Beethoven’s technique in this symphony. In at least twenty works in sonata form he had already been successful in a range of bold experiments far exceeding that covered by Haydn and Mozart : and it now interested him to write a small and comic sonata for orchestra. After Ex. 3 he strikes a deeper note; and the passage in which that theme descends into dark regions around its minor mode, while an oboe sings plaintively above, is prophetic of the future Beethoven in proportion as it is inspired by Mozart. Several other themes ensue. The development is terse and masterly, and the coda is more brilliant and massive than Mozart’s style would have admitted.

The slow movement begins, like its more enterprising twin-brother, the andante of the C minor String Quartet, op. 18, No. 4, with a kittenish theme treated like a fugue.

Ex. 4.

Here again, as in the first movement (and not as in the C minor Quartet), the second subject follows with no further transition than a taking of the old dominant chord for the new dominant key.

Ex. 5.

Two other themes follow; the second being notable for its underlying drum-rhythm. Beethoven got the idea of using C and G drums in this F major movement from Mozart’s wonderful Linz Symphony.

Dr. Ernest Walker has well observed that the minuet is a really great Beethoven scherzo, larger than any in the sonatas, trios, and quartets before the opus fifties, and far more important than that of the Second Symphony. I quote the profound modulations which lead back to the theme in the middle of the second part.

Ex. 6.

The trio, with its throbbing wind-band chords and mysterious violin runs, is, like so many of Beethoven’s early minuets and trios prophetic of Schumann’s most intimate epigrammatic sentiments. But, as Schumann rouses himself from romantic dreams to ostentatiously prosaic aphorisms, so Beethoven rouses himself to a brilliant forte before returning to the so-called minuet.

The finale begins with a Haydnesque joke ; the violins letting out a scale as a cat from a bag.

Ex. 7.

The theme thus released puts its first rhythmic stress after the scale, as shown by my figures under the bars. It has a second strain, on fresh material.

Ex. 8.

The transition takes the trouble to reach the real dominant of the new key. The second subject begins with the following theme·

Ex. 9.

and, after a syncopated cadence-theme, concludes with a development of the scale figure.

The course of the movement is normal, though brilliantly organized, until the coda in which an absurd little march enters, as if everybody must know who it is.

Ex. 10.

As it, like every conceivable theme, cap be accompanied by a scale, the Organic Unity of the Whole is vindicated as surely as there is a B in Both.

SECOND SYMPHONY IN D MAJOR, OP. 36

1 Adagio mol to, leading to 2 Allegro con brio. 3 Larghetto. 4 SCHERZO, Allegro. 5 Allegro mol to.

The works that produce the most traceable effects in the subsequent history of an art are not always those which come to be regarded as epoch-making. The epoch-making works are, more often than not, merely shocking to just those contemporaries best qualified to appreciate them ; and by the time they become acceptable they are accepted as inimitable. Even their general types of form are chronicled in history as the ‘inventor’s’ contribution to the progress of his art, only to be the more conspicuously avoided by later artists. Thus Beethoven ‘invented’ the scherzo ; and no art-form has been laid down more precisely and even rigorously than that of his dozen most typical examples. Yet the scherzos of Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn, and Brahms differ as widely from Beethoven’s, and from each other, as Beethoven’s differ from Mozart’s minuets. The nearest approach to a use of Beethoven’s model is to be found where we least expect it, in the grim and almost macabre scherzos of Chopin.

Far otherwise is it with certain works which immediately impressed contemporaries as marking a startling advance in the art without a disconcerting change in its language. Beethoven’s Second Symphony was evidently larger and more brilliant than any that had been heard up to 1801 ; and people who could understand the three great symphonies that Mozart had poured out in the six weeks between the end of June and the 10th of August 1788, would find Beethoven’s language less abstruse, though the brilliance and breadth of his design and the dramatic vigour of his style were so exciting that it was thought advisable to warn young persons against so ‘subversive’ (sittenverderblich) a work. What the effect of such warnings might be is a bootless inquiry; but Beethoven’s Second Symphony and his next opus, the Concerto in C minor (op. 37), have produced a greater number of definite echoes from later composers than any other of his works before the Ninth Symphony. And the echoes are by no means confined to imitative or classicist efforts: they are to be found in things like Schubert’s Grand Duo and Schumann’s Fourth Symphony, works written at high noontide of their composers’ powers and quite unrestrained in the urgency of important new developments. Indeed, Beethoven’s Second Symphony itself seems almost classicist in the neighbourhood of such works as his profoundly dramatic Sonata in D minor, op. 31, no. 2; while we can go back as far as the C minor Trio, op. 1, no. 3, and find Beethoven already both as mature and as sittenverderblich in style and matter.

The Second Symphony begins with a grand introduction, more in Haydn’s manner than in Mozart’s. It is Haydn’s way to begin his introduction, after a good coup d’archet, with a broad melody fit for an independent slow movement, and to proceed from this to romantic modulations. Mozart, on the rare occasions when he writes a big introduction, builds it with introductory types of phrase throughout. Beethoven here makes the best of both methods ; and the climax of his romantic modulations, instead of ending in one of Haydn’s pauses in an attitude of surprise, leads to a fine quiet (‘dominant-pedal’) approach, in Mozart’s grandest style, that finally runs without break into the allegro. Contemporaries were probably the last to feel, as we feel, the ‘influence’ of Haydn and Mozart in all this; for this is in all respects the real thing, and Beethoven was the only survivor of Haydn and Mozart who could do it.

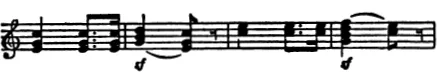

The main theme of the first movement—

Ex. 1.

has often been quoted thus far as an example of complacent formalism ; but if you get to the end of the paragraph you will not accept that view. The sentence fills eighteen bars (overlapping into the next sentence), and takes shape, not as a formal sequence, but as an expanding melody by no means easily foreseen in its course or stiff in its proportions.

The main theme of the second subject—

Ex. 2.

has a certain almost military brilliance, which is in keeping with the fact that nobody wrote more formidably spirited marches than Beethoven.

Towards the end of the exposition, the semiquaver figure (a) of the ‘compl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- J. S. Bach

- C. P. E. Bach

- Beethoven

- Berlioz

- Brahms

- Bruckner

- Dvořák

- Elgar

- Franck

- Haydn

- Gustav Holst

- Mahler

- Mendelssohn

- Mozart

- Schubert

- Schumann

- Sibelius

- Smetana

- Richard Strauss

- Tchaikovsky

- Vaughan Williams

- Wagner

- Weber